It’s easy to forget from the perspective of 2020 that, when it first crept onto the scene in the 1980s, the erotic thriller had an air of the fantastical about it. The subgenre was certainly codified with more grounded, real-world films such as FATAL ATTRACTION and BASIC INSTINCT, but in its earliest days there was a certain air of whimsy and experimentation. FLASHDANCE, arguably the film that laid the groundwork for what would become the erotic thriller, asked audiences to believe in an ochre-lit, Mrs. Maisel–esque universe in which a bunch of working-class stiffs congregated every evening not at a seedy strip joint but at new-wave cabaret shows. This high-concept approach continued with material such as 9 ½ WEEKS, with its proto-FIFTY SHADES relationship between Mickey Rourke and Kim Basinger incorporating such set pieces as crossdressing roleplay fantasies played out in five-star restaurants and rain-soaked fistfight/fuck sessions. Eventually, directors would realize that audiences were more interested in seeing attractive people with bad air and skimpy clothes get down to it, and that anyone in want of artier fare always had European cinema to turn to; but for a brief, shining moment, there was a fantastic crossover in American cinema between good old fashioned sleaze and Art Museum surrealism; and nowhere was that more brilliantly — or weirdly — realized than in TWO MOON JUNCTION.

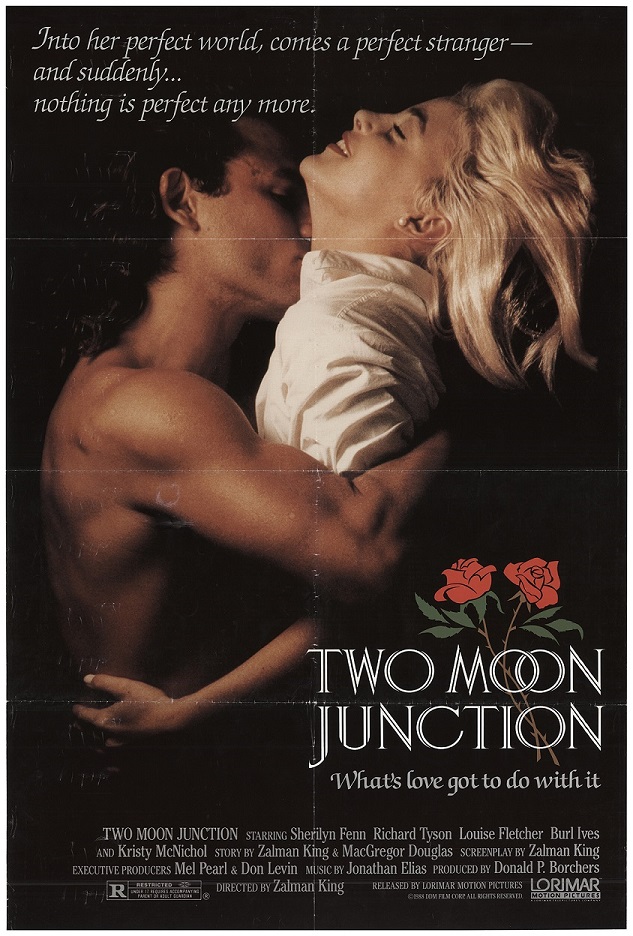

If you had cable in the early ’90s — and especially if you were a teenager — TWO MOON JUNCTION almost needs no introduction. Even if the name doesn’t ring a bell, odds are you have seen this movie (it was on constantly circa 1991), and you definitely know the creative powers behind it. Boasting a “written and directed by Zalman King” credit, TWO MOON JUNCTION was the first directorial effort by the man whose unique — and, quite frankly, insane — vision was almost singularly responsible for the erotic thriller boom of the decade. Adrian Lyne may have been more financially successful, Joe Eszterhas more notorious, but when it came to an authoritative voice dedicated to shifting the paradigm on arty fucking on film, Zalman King was the Scorsese of smut. His film THE RED SHOE DIARIES not only provided X-Files fans with the incongruous sight of a horny and grief-stricken Agent Mulder getting off to his dead wife’s sex memoirs, but it laid the groundwork for the RED SHOE DIARIES television series, a program that served as the gold-standard for serialized erotic thrillers before the format sank into self-parody. If you peeped on late-night cable TV in the ’90s, it either owed its lineage to King or flowed directly from his mind—between 1980 and 2010, he produced twenty-eight different movies and television series (including 9 ½ WEEKS), in addition to writing eighteen and directing twenty eight (bonus for exploitation fans- he also plays the lead role of Jerry Zipkin in the 1978 LSD freakout shocker BLUE SUNSHINE). While his imitators would cherry pick aspects of his style, from brooding atmospheres and haunted, ambiguously dangerous men finding themselves in sexy situations, only King himself had the audacity to double down on his own weirdness and craft films that took place in their own deranged approximations of reality — and with TWO MOON JUNCTION, he came out of the gate swinging.

TWO MOON JUNCTION takes place not so much in our world, but one which is something of a cross between GONE WITH THE WIND by way of AMERICAN PSYCHO, as re-written by Flannery O’Connor and shot by David Lynch. Our Scarlett O’Hara/ Patrick Bateman analogue is a young debutante by the name of April (played by a pre-Twin Peaks Sherilyn Fenn), scioness of the powerful Alabama Delongpre family (that’s not a typo, and, yes, it’s pronounced exactly how it sounds). Superficially charming, vivacious, and the very picture of sweet southern gentility, it’s pretty clear from the get-go that something is missing from April’s life. After meeting her milquetoast fiancée, Chad — a guy so terminally bland that he’d probably consider The Carpenters too punk for his tastes — an audience could be forgiven for assuming that missing something is a modicum of passion. While that’ll certainly prove true, there’s also a coldness at her core that indicates what’s really missing is what we might generally conceive of as a soul; I’m getting ahead of myself, though.

Amidst a flurry of cotillions and coming-outs and whatever else it is that rich, white Southern people with way too many articles of white linen clothes do, a cut-rate carnival roles into town, presided over by the mysterious dwarf Mr. Smiley (Fantasy Island’s Hervé Villechaize, in his final film role). Intrigued by the prospect of some common folk fun, April and her giggling-mess little sisters avail themselves of the rides and games, in the process drawing the attention of Perry (Richard Tyson), a sentient piece of meat with Fabio hair and the mind of an ape trained to kill. Equal parts lust, rage, and alcoholism, Perry immediately sets his sights on bedding April. He quickly achieves his goal after he sneaks a peak at her driver’s license and breaks into her house one afternoon, where he sets about a rapid-fire game of seduction by VCR (for all of my younger readers, you simply could not underestimate the power of a good VCR in 1988). Of course, April is supposed to be a good girl, the granddaughter of arch-matriarch Belle Delongpre (a slumming Louise Fletcher, who plays the role with a kooky pseudo-New Orleans drawl despite actually being southern). Belle is a consummate survivor, a woman who’s built and maintained her family’s legacy on cold calculation and altruistic asceticism, not jumping into bed with every hot piece of ass who’s roamed her way. It’s not long before April learns of her heir’s dalliance, and comes to fear that it’ll upset the empire she’s worked to build, especially as April develops a fascination with carnival life and begins spending time with Perry and his cohorts. With the wedding date approaching, Belle proves herself willing to go to any lengths — including murder — to secure the family’s future.

You cannot do justice to the utter shitshow of insanity that is TWO MOON JUNCTION without seeing it firsthand, but I’ll try. While the film begins in pretty standard “sad rich girl falls for hot poor boy” territory, it very quickly goes off the rails, beginning with April’s first post-coital return to the carnival. Looking for Perry, April instead finds Patti Jean (Kristy McNichol in off-brand Caroline Williams mode), a heretofore unseen, ambiguously bisexual trucker who pops up out of the ether to inform us that a seriously inebriated Perry needs more booze. Patti proceeds to whisk April away on a bizarre sidequest to score, eventually landing in a weird, all-night truck stop with the wrong number of walls, where she delivers a monologue instructing April on the proper way to apply lipstick to her nipples. In a Lynch movie this would be intentionally surreal, a purposeful hard-left-turn into off-the-wall territory. Here, there’s no indication that King thinks this is weird at all; you can tell he sat down at a word processor, wondered what the next logical narrative choice was for his erotic thriller, and decided “lipstick nipple trucker.” The same is true for Mr. Smiley, who’s portrayed as a diminutive figure of almost Satanic evil, popping up in the aftermath of a tragic accident to monotonously intone “Money!” in response to everything, with a hard, drawn-out emphasis on the first syllable (Moe-nee). Then there’s a riot, a funeral for a dog, an epic sequence of the carnival leaving town juxtaposed against April and Perry hooking up again, and an attempted murder subplot involving a Boss Hogg-esque sheriff played by Burl Ives in his last film role (TWO MOON JUNCTION was not kind to TV stars of the ’70s). It all culminates in a fever-dreamy sequence in which April lures Perry to the titular Two Moon Junction, a swampland flophouse where Sherilyn Fenn delivers a totally-nude spoken word piece about pulling a train on her cousins. However weird you’re imagining all of this — you’re right.

At least part of the film’s sensibility appears to derive from King’s own background and perspective. King was a Northern Jew who shared our people’s fascination with the trappings of preppie culture broadly and Southern gothic specifically. From Ralph “Lauren” Lifshitz helping to craft the aesthetics of preppie culture through the lens of Ashkenazic Jewish sartorial aspirations to writers such as John Bloom and Kinky Friedman who’ve adopted the personas of range-roving cowboys, there’s a long and storied dialogue between Jewishness, American Old Money, and the Old South, and TWO MOON JUNCTION appears to be an examination of a specific manifestation of cultures as refracted through King’s own unique sociological prism. The Old South here isn’t the one of GONE WITH THE WIND but something approaching a burlesque of it, a version of Alabama where women are always in white and men are always in tuxedos and powerful bitch goddesses machinate and scheme behind the scenes as their dimwitted men engage in homoerotic displays of impotent masculinity. It’s hard to articulate the precise ontological perspective King brings to the proceedings, but for any Jewish person who’s ever visited — or better yet, lived in — the South for an extended period of time, it’s immediately recognizable; the truly difficult part is in determining whether it’s a wry burlesque or some sort of weird wish fulfillment fantasy.

A final word- I mentioned April’s apparent soullessness, and it’s here that TWO MOON JUNCTION narratively differentiates itself from its successors in much more meaningful ways beyond its dalliances with the absurd. One of King’s goals with TWO MOON JUNCTION was to give female viewers their own guilt-free escapist fantasy. After all, countless ’70s movies had portrayed caddish, good-looking men running around on their wives without a second thought; King wanted women of the ’80s to have their own alternative. Sherilynn Fenn — who’s in top cinematic form here, and makes me sorry she didn’t do more film work post-Twin Peaks — brings a degree of coldness to April, though, that speaks to something approaching psychopathy. She cries after her first tryst with Perry, but it’s difficult to determine whether it’s feelings of remorse or fear she’ll be found out. By the time she’s gliby seducing Perry herself with cornpone platitudes about the unpredictability of Southern Girls, her ability to cheat on her fiancée without any repercussions doesn’t seem to come about in spite of her conscience, but rather due to a lack of one. Then again, maybe all those guys in ’70s movies were similarly conscienceless; perhaps we just didn’t notice because we expected them to be bastards, while April’s infidelity shocks precisely because it’s so against cultural norms.

TWO MOON JUNCTION achieves a lot in spite of itself. It’s an erotic thriller that manages to be genuinely erotic in spite of what would become the parodic trappings of the genre; it’s a surrealist masterpiece that stands alongside the works of Lynch and even Cronenberg for sheer stylistic madness; it’s an audaciously batshit work of lunacy. It may not be good, but it is sexy, and unique, and unlike anything you’ve probably seen before, and, for that — and all the influence it would have on the madness of the decade to follow — it’s certainly worth a second look.

Tags: Burl Ives, Dabbs Greer, Hervé Villechaize, Juanita Moore, Kristy McNichol, Louise Fletcher, Milla Jovovich, Richard Tyson, Sherilyn Fenn, The 1980s, zalman king

I would agree with your take on this bizarre masterpiece, with the exception of the crying after sex. I always took that as the repression from her Southern Belle life finally finding release. The unfurling of the wilder parts of herself that had been hungry and not fed. There is a coldness there definitely, and an anger. She’s used to being in control, and resents someone else having the key to what she now knows she wants. I do love that she goes after what she wants in a liberated way, but it’s a way to stay sane in the role expected of her.