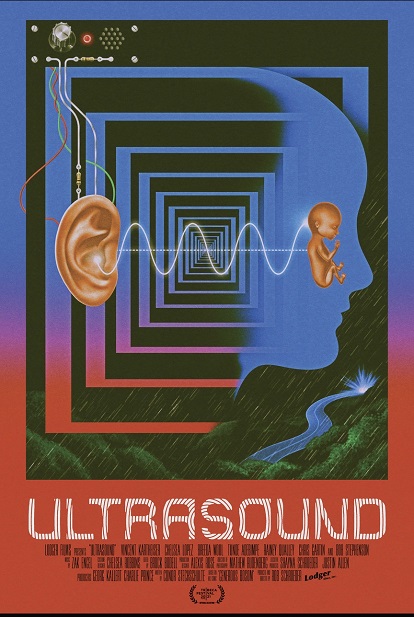

How’s this for a classic horror scenario: during a dark and stormy night, a man on his way home from attending a wedding has a flat tire on a remote highway, and must seek assistance at the only nearby house. The inhabitants of that house are eerily eager to help, as husband Art (Bob Stephenson) and younger wife Cyndi (Chelsea Lopez) pay a great deal of attention to Glen (Vincent Kartheiser) and his welfare. The couple are all too happy to offer Glen any comforts they have, everything from food and drink to a bed for the night to, well, Cyndi herself. While on the surface this may seem like a young single man’s dream, Glen is weirded out, and he’s right to be, as Art seems oddly pushy about Glen sleeping with Cyndi. Sure, this could be Art’s “fetish thing,” as Glen postulates, but then there’s the matter of the strip of nails in the road that caused Glen’s flat tire. There’s clearly something unusual at work here, and the tried-and-true setup of these opening scenes promises secrets and subversion to follow.

Unfortunately, that’s precisely where ULTRASOUND falters, as it tries to subvert so many things at once that it ends up pulling the rug out from under itself. Immediately after that cold open and a brief title card, the film cuts to a series of seemingly unrelated characters: a shady political hopeful (Chris Gartin) and his secret girlfriend (Rainey Qualley) who appears pregnant in some shots and not pregnant in others, and later, a psychological researcher (Breeda Wool) and her boss (Tunde Adebimpe) cryptically discussing their latest patients, their treatment somehow involving the memorization of dialogue that Glen and Cyndi have spoken in earlier scenes. The movie, in other words, shifts so rapidly from a place of narrative structural comfort into disorienting confusion that any delight one might take in being so caught off guard is squashed by the frustration of being completely untethered.

The screenplay by Conor Stechschulte is an adaptation of his graphic novel entitled “Generous Bosom,” and it’s no surprise to discover that Stechschulte has no other credited experience working on feature films. While the narrative disorientation and constant shifting of focus present in ULTRASOUND would likely function well on the page, on screen it gets real old real fast. Not helping matters is director Rob Schroeder’s commitment to his writer’s approach, switching up the movie’s tone with almost each scene, bouncing between dread-filled moments of ominousness and coyly satiric, dry depictions of everyday occurrences. ULTRASOUND’s blend of part indie dark comedy, part sci-fi headtrip movie and part hallucinogenic horror might have worked had Stechschulte and Schroeder let the audience in on at least some part of the gag early on, yet their insistence on attempting to make the viewer just as manipulated as the movie’s characters are is a choice that kills the movie long before it lays its cards on the table.

The best way to describe the film is like an M. Night Shyamalan movie in partial reverse: where that filmmaker loves to tell stories that initially have a seemingly rigid and simple structure before it’s revealed that there’s a bigger high concept idea behind it, ULTRASOUND tells the audience right in the first twenty minutes that there’s a bigger notion at work, yet refuses to reveal what it is almost until the last half-hour of the movie. Thanks to Schroeder telegraphing that all we see is not to be trusted, it’s incredibly difficult to become emotionally or intellectually invested in the goings on, since it seems possible that none of what we’re being shown will end up mattering, or at least not in the way it appears to. It would help if the film provided a strong identification character to follow, but it refuses to do that, too. Clearly, Stechschulte is still in the graphic-novel mode of jumping between an ensemble of characters and their points of view, but Schroeder isn’t able to make the movie’s ensemble cohesive. By the time Wool’s Shannon steps up to become the closest thing the film has to a protagonist, it’s too little, too late.

Once the narrative reveals happen (or most of them, at least), ULTRASOUND becomes mildly engaging as its pieces somewhat fall into place. The intellectual engagement the movie is sorely missing for its first two-thirds is retroactively applied, making what initially seemed like bizarre context-less moments early in the movie more interesting. Yet Schroeder only flashes back over one of these scenes (the opening classic horror scenario, in fact), since there’s no time to go back through the entire movie up to that point. This structural imbalance leaves any enjoyment of the story’s admittedly bold concepts and themes hollow — sure, ULTRASOUND may play much better upon a re-watch, but if the initial watch is this unfulfilling, the idea that anyone might be enticed to watch the movie again is unlikely.

ULTRASOUND’s influences are a melange of surreal, avant-garde literature and cinema. The film wants to be a Philip K. Dick-like dark satire that touches on everything from Cronenbergian body horror to Lynchian dream logic to Vonnegut political commentary and Adult Swim horror infomercials. Yet what ULTRASOUND lacks that those authors and filmmakers have is a sense of control and purpose — by contrast, the movie feels like it’s grasping at straws, sinking beneath its try-hard veneer of weirdness. As any hypnotist will tell you, in order for hypnosis to work the subject must be properly primed and be made open to being susceptible to suggestion. In other words, they have to be able to suspend their disbelief, and while ULTRASOUND may have a lot of potential to sustain a compelling spell, it fails to cast it.

Tags: Adaptations, Bob Stephenson, Breeda Wool, Chelsea Lopez, Chris Gartin, Conor Stechschulte, Graphic Novels, Matthew Rudenberg, Rainey Qualley, Rob Schroeder, Sci-Fi, Tribeca Film Festival, Tunde Adebimpe, Vincent Kartheiser, Zak Engel

No Comments