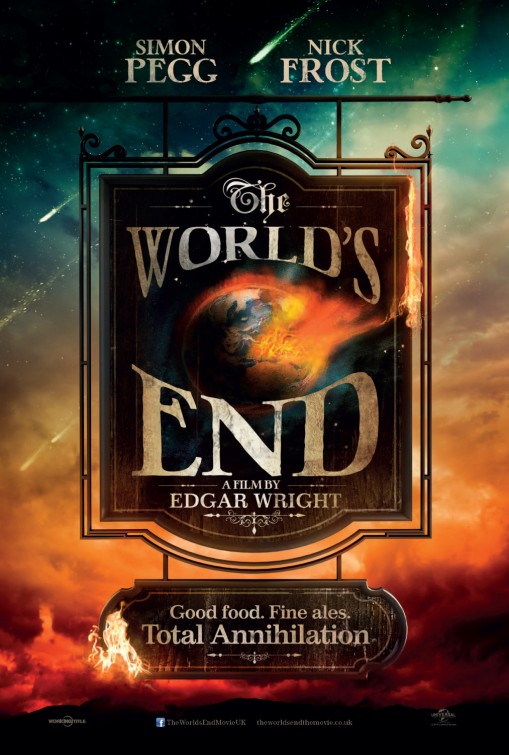

Edgar Wright’s THE WORLD’S END is a comedy/action/sci-fi film celebrating its five-year anniversary that is a hilarious take on Invasion of the Body Snatchers by way of corporate sterilization. But beneath the excellent throwback soundtrack, the great fight sequences, and brilliant comedic dialogue there runs a darker element in the movie (co-written by Wright and Simon Pegg). For while it is a fun and diverting cinematic experience, Wright and Pegg are able to inject a realistic element in the fantastic tale through the suicidal depression affecting the main character, Gary King (Pegg). The script accurately depicts the treatment and mindset of a depressive, but also turns some of the most common issues facing those with depression into parts of the film’s themes and plot. By infusing a lighthearted apocalyptic romp with this serious subject matter, the filmmakers show a true understanding of the arresting power of depression.

Before going on, it’s probably in the best interest of all involved if I establish my bonafides for this topic. I have been suicidal with depression since I was about 12 years old, though I wasn’t formally diagnosed with it until I was 25. In my 36 years on this planet, I’ve attempted suicide multiple times — surviving through incompetence, fate, or (in my last attempt) stopping myself midway and seeking professional help. I studied psychology in high school and college, and, being of the nerdy disposition, read a lot on the subject matter since my diagnosis. I’ve been in some form of therapy now for 10 years and on some form of medication for about 9. I’ve gone through multiple psychologists, psychiatrists, and pharmaceutical cocktails in order to find ways to best curb my self-destructive tendencies and quell my automatic thoughts that bid me to kill myself. I have been hospitalized for my mental illness. I say all of these things to point out that I know of what I speak.

THE WORLD’S END is about a great many things — nostalgia, friendship, substance abuse, conformity, ’90s industrial music, identity — all wrapped up in scenes that are equal parts thrilling sci-fi speculation, hilarious comic banter, and exhilarating fight choreography. It’s not accurate to say that the movie is “about” any one thing, as it covers so many topics and genres in its running time. But the element that always stood out to me, since seeing it in theaters five years ago, was the current of honest discussion about, and hallmarks of, depression. The story opens with King recounting the height of his life, when in high school he and his friends attempted his hometown’s pub crawl before it all went awry. The fast-cut assemblage of exposition and character profiling with a wistful King looking back at his drunken misadventures ends with him saying, “As I sat up there, blood on my knuckles, beer down my shirt, sick on my shoes, knowing in my heart life would never feel this good again. And you know what? It never did.”

The idyllic portrait of youth in revolt is immediately juxtaposed against a now adult King sitting in a group setting where he’s just given this monologue. A circle is set up with uncomfortable plastic chairs in some repurposed common room, all under soul-washing fluorescent lights, with people half-heartedly listening to Gary’s tale. But, what I was immediately struck by when I first watched this film and what clued me in to the subtext that would resonate with me were the shoes; specifically that none of them had any laces.

It’s a small, subtle thing that my eyes flitted on, but instantaneously told me what was happening in the scene. Shoelaces, like belts and other lengthy bits of material that can be used for strangling, are traditionally removed in psychiatric programs. I had to surrender my own when I was on the psych ward—I even had to sign a contract and promise to three different people that I wouldn’t harm myself, in order to get my headphones back to listen to music. This powerful cut from the golden years of King’s history to the drab status of his current life doesn’t just show the disconnect between promise and reality, it also suggests the unfortunate undercurrent that ran through Gary’s life and has led to a drastic and dramatic event that lands him in group therapy session in a psychiatric program talking about his past.

With this quick insight gained, it wasn’t hard to start filtering a lot of King’s actions through the filter of depression. Of course, like everyone else, King isn’t just his mental health problems. He has personality and issues that aren’t directly related to depression — he lies and manipulates, is self-obsessed, defiantly ignorant with an unearned sense of arrogance. These behaviors may have some roots in his depression, but ultimately they are just dickish moves. But what Wright and Pegg do with their script is to actualize some very common thought patterns that many with depression experience.

Never/Always Vision

People who haven’t experienced it tend to think of depression as simply an emotional state or one being in a low mood often. That’s how people express their depression, but really it has more to do with cognitive biases. In everyone, the brain sets up reactions to stimuli and uses that to determine best course of action and how to interact with the world. For those with depression, there are inherent biases that skew logic and color perception, making it hard to properly see the world and react accordingly. One example is that the mind only picks up on specific elements of an event, and uses that for a massive generalization that comes with such certainty it’s hard to argue against. In King’s case, he romanticizes the past despite all the evidence that it wasn’t all sunshine, and then believes it will never be that good again. The future is unknowable—even more so if intergalactic robots are involved—so the assumption that things are utterly incapable of changing and will only be terrible feeds into his worldview and sustains his depression. He’s wrong in thinking that “back then” was all great, and he’s incorrect that everything going forward will be all bad. Depression tends to obliterate moderation, removing nuance and leaving behind only absolutes. In his impossible pursuit to reclaim the past, running away from the future, King is trying to find a way to not face his fears that life will be horrible forever.

Mental Filter

As described above, depression tends to rely on a very skewed mental filter to persuade those suffering from it. Many with depression will make sweeping proclamations like “everything is terrible” or “nobody cares.” When challenged with specific examples of positive things in their life or acts of people showing interest and love, these will be diminished. “That doesn’t count.” And people with depression aren’t trying to be dismissive — their brains are such that they put weight unevenly on different events. It’s a cognitive loop where the bias that depression creates has to be confirmed, so it tosses out any competing information that would muddy the argument. Similarly King blazes forward with his undeserved arrogance, dismissing any who point out his faulty logic or inaccuracy. While his mental filter isn’t the typical one that only focuses on the negative, it nevertheless shows a tunnel vision approach to the world where he only selectively listens and gives credence to the few things that align with his worldview.

Fixation

While this is more indicative of obsessive tendencies, fixation is a common pitfall for many depressive types. Not only do people with depression lock in on the negative aspects of their lives, but some also pin their hopes on one change to solve all their problems. “If I got this job…” or “if I was married…” or some individual goal suddenly represents the cure all for their woes. If they can do this one thing, then everything else will line up accordingly and they won’t feel so terrible all the time. Of course, it’s not one thing that will be the solution to depression, but changing approaches and reactions to a whole host of situations while working on improving the thinking processes that bog them down so much. For King, his fixation on the Golden Mile shows a lack of understanding of the encompassing nature of his mental health. There is no real plan or elaboration about how this pub crawl will actually make a difference, but he’s placed so much weight and importance on it that it becomes a detrimental driving force. He disregards his own safety and the safety of his friends to see it through, because he fundamentally believes that somehow by doing this task he will be able to reclaim his youth and reset his life.

Watching THE WORLD’S END, I was of course struck by Wright’s incredible visuals and pacing, and the way he and Pegg craft an airtight script full of foreshadowing and allusions and hilarious banter. But I also saw a lot of myself on the screen in ways that most movies dealing with depression have never achieved. Many films only depict depression in the shadow of a suicidal noose or something equally dire. It’s rare to see those internalized biases realized in cinema, and recognize those pitfalls that I stumble into. King and I aren’t particularly similar, but in this comic tornado of a person, Wright and Pegg crafted a self-destructive person that is adrift in their own sea of troubles and desperately trying to stay afloat. I spent the running time enraptured by the action and laughing at the gags, but I also watched it in amazement as the mental endgames depression crafts translated into this flawed man. Being able to see that, to be outside of myself and recognize these biases and patterns, helped me realize that I’m at a different place now then when I took a knife to my wrists; I was able to see that progress has been made and hope exists for all of us. Even Gary King.

Wright and Pegg crafted a deeply rich and fulfilling story that is adventurous and uproarious but also incredibly human and somewhat painful. The substance abuse that King exhibits is a symptom of his depression, as it is for so many, but also appears like it may be based on Pegg’s own struggles with mental health and drinking. THE WORLD’S END culminates not with King cured of his issues nor receiving his dream goal of reliving his past. Instead, he has seemingly been able to address the symptom of drinking and now has assembled a new, quieter life with his gang of Blanks. He’s literally on the road to recovery as he journeys onwards with his new compatriots. It’s a synthesis of the old and the new to produce something unique that carries him through the wasteland and allows him to finally be able to progress from the hold depression has on him. Good films are entertaining, but great films take on deeper issues and meanings when people watch them. THE WORLD’S END is great because it does so many things perfectly, often outlandishly, but it never loses sight of the frail humanity at its core.

Tags: Alice Lowe, Aliens, Bill Nighy, Bill Pope, comedy, David Bradley, Eddie Marsan, Edgar Wright, Garth Jennings, Kylie Minogue, Martin Freeman, Nick Frost, Paddy Considine, Paul Machliss, Peter Serafinowicz, Pierce Brosnan, Rafe Spall, Rosamund Pike, Sci-Fi, Simon Pegg, Steven Price

No Comments