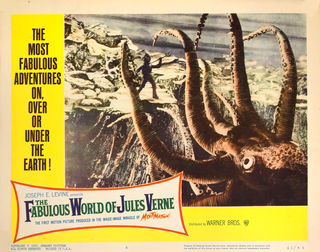

At the risk of overselling the appeal of Karel Zeman’s VYNÀLEZ ZKÀZY — literally THE DEADLY INVENTION, or, as it’s known in the U.S., THE FABULOUS WORLD OF JULES VERNE —I’m going say it’s one of the best fantasy films you’ve never seen. Never, that is, if you’re an American under the age of 50 or so. And even if you’re over 50, there’s a good chance the title doesn’t sound familiar, but I suspect the memory of it might lurk in the corners of your mind, perhaps labeled “Movie I Probably Imagined.”

The reason you might doubt your memory of the film is that it pretty much disappeared in the U.S. after the mid-1970s. Released to acclaim in Zeman’s native Czechoslovakia in 1958, the film made it to these shores in dubbed form in 1961, and despite good reviews (Pauline Kael gave it a rare rave, and in the New York Times, Howard Thompson called it “a frisky, stylish fantasy — and a real tonic for tired eyes”), it sank at the box office. However, it lived on in the form of kiddie Saturday matinees — I’d say I caught it at my local theater somewhere around 1970. (For that matter, I saw another Zeman film, 1955’s JOURNEY TO THE BEGINNING OF TIME, originally CESTA DO PRAVEKU, around the same time, at the same theater. That, too, made the Saturday matinee rounds for a long, long time.)

I dimly remember some TV screenings on an independent New York City TV station in the early/mid-’70s, but after that, the film was gone—whether because of rights issues or just the fact that it was shot in black and white and therefore was seen as being less valuable — but it would occasionally haunt me with some images that I couldn’t quite place and made me wonder if I had merely dreamed them.

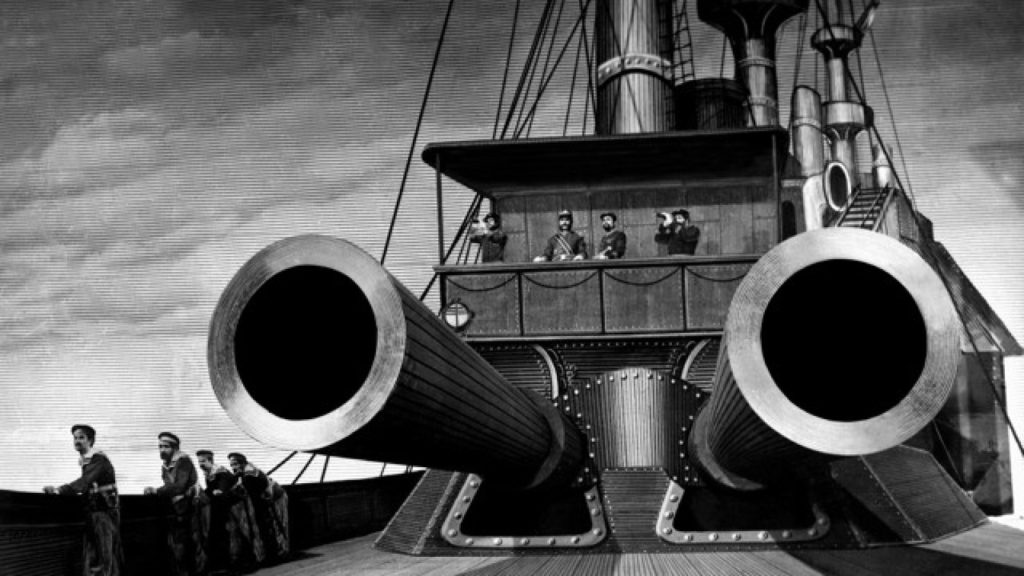

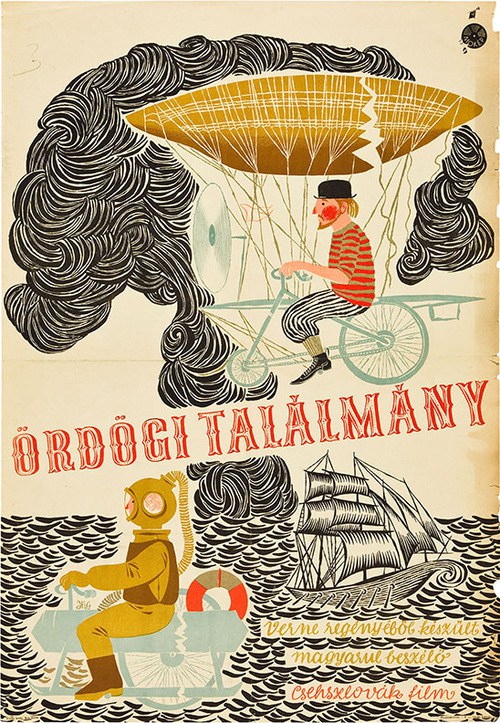

The reason the film seemed likely to be a figment of my imagination is that it resembles nothing else that came before it (or after, for that matter). Using a combination of animation, live actors, and specially designed sets, Zeman achieved the effect of a Victorian era steel engraving come to life. Every image is covered in what appears to be thousands of crosshatched and parallel lines, as in an illustration published in a 19th century book.

In her review, collected in 5001 Nights at the Movies, Kael described the look of the film like this: “The variety of tricks and superimpositions seems infinite; as soon as you have one effect figured out another image comes along to baffle you… There are more stripes, more patterns on the clothing, the decor, and on the image itself than a sane person can easily imagine.” Sometimes the entire image is animated; sometimes the live actors and sets are inserted into the animation; and sometimes only the actors on the fantastical sets are on view. And yet the effect is surprisingly seamless.

The plotline is said to come mostly from Jules Verne’s Facing the Flag, though there are elements from 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea and Robur the Conqueror. The main character, Simon Hart, travels over the ocean by steamship to see his mentor/boss, Professor Roch, who is badly in debt and needs funds to continue working on his research project, “the secret of matter.” Shortly after Hart arrives, however, he and Roch are kidnapped by pirates and taken to a ship owned by the dastardly Count Artigas, and then to his giant submarine, hidden beneath the boat.

Artigas tells the professor that he wants to bankroll his experiments, which Roch will be able to perform in Artigas’s secret base; Hart, meanwhile, is held captive in a cell. But before they can make it to the base, the boat’s captain spots another ship in the distance, and Artigas gives the command to ram and sink it. The Amelia falls to the bottom of the ocean, and in perhaps the film’s best sequence, the pirates ride individual vehicles — picture underwater bicycles — to the wreck in order to capture its treasure. There’s a great shark attack in this sequence as well.

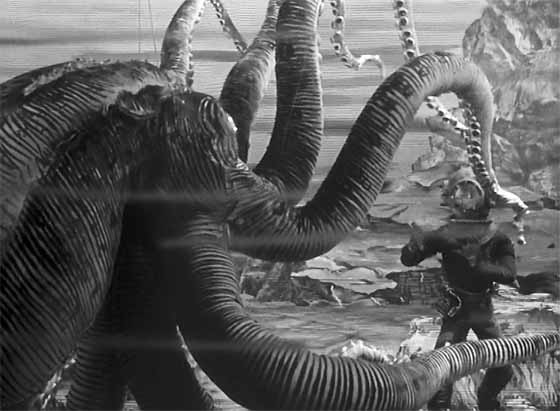

When they reach Artigas’s hidden base, Roch works on his invention, which might be described as a Victorian version of an atom bomb. Hart, meanwhile, plots his escape, and volunteers to help repair a damaged cable in order to gather information. In another great underwater sequence, one of Hart’s minders is attacked by an octopus, and in the confusion that follows, Hart manages to escape. Eventually, Roch realizes why Artigas wants the deadly invention, and, in the explosive climax — which seems influenced by Cold War nervousness — makes sure the Count doesn’t get it.

The film is filled with memorable images: Steampunk-looking airships. A proto film projector that resembles a gigantic View-Master. Camels on roller-skates. That octopus attack. Fish that morph into hallucinated underwater butterflies. Subs with flippers that make them glide under the water like metal turtles. The film never stops offering unique, memorable images.

In preparation for writing this column, I watched the original and dubbed American versions back to back — and found that, to my surprise, the U.S. version is mostly untampered with. THE FABULOUS WORLD OF JULES VERNE, released by Joseph E. Levine, contains only minor cuts (judging by the running times), and the structure and music track of the original remain intact. The dubbed dialogue (there isn’t a lot of it, as the story is mostly told through images) mostly sticks to the meaning of the original Czech, based on the English subtitles on the Czech version. Occasionally, the dub track explains a little bit more than the original dialogue did, but not in a way that seems intrusive. The same goes for Simon Hart’s narration.

I’ve read that the original American release also had a brief intro by Hugh Downs, but I don’t recall this from the matinee I saw way back when, and I also don’t think that TV prints carried this, either. Certainly, it’s missing from the public domain videos of the U.S. cut that exist today.

You have a few options if you want to see the film. Unfortunately, the original Czech version has never been released here on DVD; however, the Karel Zeman Museum in Prague recently restored the film (and other Zeman titles) in association with Czech TV. It’s available via Amazon in a Region 2-coded DVD and a Region B/2-coded Blu-ray. The dubbed American version is available on an unauthorized DVD, most probably from a TV print.

Streaming availability comes and goes. Currently, the American version is available divided into multiple parts on YouTube, but two of the parts appear to be missing, so I can’t recommend viewing it there. Furthermore, it’s a soft, blurry print. The Internet Archive has had a fairly sharp Czech copy for quite a while, but for a long time, it had no subtitles. But the version there as of this writing has very nice, very readable subtitles. Until Criterion or some other caring label chooses to give this a well-deserved release — with some shorts, please! — that may be your best bet.

Other Zeman ephemera can be found on YouTube and Amazon Video. The 11-minute 1949 short “Inspirace” is on YouTube here, and a trailer for the restored version of VYNÀLEZ ZKÀZY is here. A 24-minute documentary about Zeman is available to rent from Amazon. And director John Landis talks about the American version, THE FABULOUS WORLD OF JULES VERNE, here — but, unfortunately, he gets quite a bit wrong. He seems to suggest that American version combines various shorts into a feature, which is not true. Still, his enthusiasm for the film comes through.

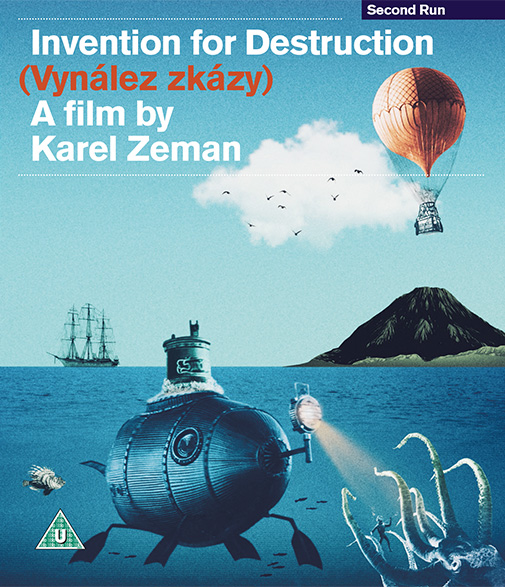

Update: The U.K.’s Second Run released an all-region Blu-ray of this film, under the title INVENTION FOR DESTRUCTION, in November, and it’s a beauty. The transfer (based on a 4K restoration using original materials) is astonishingly clear. The underwater scenes, with their clever play of perspective, fare especially well and almost look like 3-D. (Although I’d love to see what an actual 3-D conversion of this looks like — the film is practically tailor-made for it — it’s far from necessary.)

And there’s lots of bonus content. First up is the Americanized dubbed version, THE FABULOUS WORLD OF JULES VERNE, complete with the long-unseen Hugh Downs introduction. For a dub, it works quite well, mostly because there’s not much dialogue. Also included are a 16-minute appreciation from filmmaker/animator John Stevenson (who most recently helmed SHERLOCK GNOMES); two of Zeman’s shorts (“Inspirace” — listed as “Inspiration” — and “King Lavra”), mostly looking quite sharp and colorful, though not in the perfect shape of the main feature); two short featurettes on the restoration; a short showing Zeman at work on some of the effects; and another from the Karel Zeman Museum called “Why Zeman Made the Film.” Rounding out the package are thoughtful liner notes by critic/historian James Oliver.

Tags: Blu-ray, Czechoslovakia, dvd, Hugh Downs, James Oliver, John Landis, John Stevenson, Joseph E. Levine, Jules Verne, Karel Zeman, Literature, The UK, World Cinema

Nice column, Jim. I’m always happy to learn something new about a movie that’s been a particular favorite, ever since I caught the dubbed version on a local UHF channel’s late-late-night movie back in the Eighties. This is one of those times when I’m in complete agreement with Pauline. I’ve got kind of a thing for Victorian/Edwardian SF, so you can imagine how TFWoJV blew me away right from the first. Zeman really did a magnificent job of bringing those period illustrations to life.

I happened to see the subtitled version in that excellent print which was on Youtube for a short while, before it got pulled. Coincidentally enough, just a couple of months after I’d finally read “Facing the Flag”. And the movie does follow the plot of the novel pretty closely, especially the subtitled version, where the character and place names are the same as in the book.

The Czechs definitely made some interesting films, back in those days.

Jim knows that I’m not only a big fan of his film writing, but also his archeological prowess, having watched him dig up and carefully dissect some very obscure, but nonetheless fascinating fare (although it hasn’t always redounded to my benefit; I could have gone my whole life without knowing It’s All About Love exists.

Having gorged on the Internet Archive print, I realize that I did see this as a child, and later dismissed it as a fever dream. But watching it again, it’s even weirder and more dream-like than I remembered (the wavy lines that undulate in the ocean swells were almost certainly invisible on our old TV). So thanks not only for the precis and background information, but also that link.

Hank: Many thanks for your comment.

Scott: You can easily divide your life into “Before I Saw ‘It’s All About Love'” and “After I Saw ‘It’s All About Love.'”

You’re welcome. (I think.)

Jim, your DAILY GRINDHOUSE review of Karle Zeman’s 1955 FABULOUS WORLD OF JULES VERNE is excellent, greatly enjoyable and very informative ! At 67 i mostly remember from childhood (on a small b&w TV in 1962 /serialized by IHOP) his evocative JOURNEY TO THE BEGINNING OF TIME for the prehistoric creatures. A 1960s MIDI-MINUIT FANTASTIQUE Magazine brief article (Nr ?) on him includes a frontward Mammoth pic from JTTBOT, and theres also a wonderful multi-page pictorial FANTASCENE Magazine article (Nr 3, 1977) on his films that includes a small scene-pic of a Dimetrodon from his film BLACK DIAMOND, but ive never seen any other info or images from that (re-titled ?) film. But i now own and enjoy Criterion’s 2020 deluxe triple-feature Blu-ray boxset (inc JTTBOT). Zeman’s daughter produced a lavish Czech book on his films a few yrs ago, but ive not found or seen it yet.