I didn’t watch a lot in 2021.

Actually, I take that back. I saw a ton this year, it’s just that the majority of it wasn’t released in the past twelve months. I didn’t do that on purpose, it just kind of happened that way. I’m doing my best, all right? Anyways, this poses a problem when attempting to make your standard end-of-the-year recap list so, out of necessity, I’m zagging on you.

Here are some of the movies I saw this year. They vary in terms of genre and year of release, but they all share one thing in common: They won’t leave me the hell alone. You should check them out. Maybe they’ll do the same to you too.

THE AMUSEMENT PARK (2021)

Directed by George A. Romero

Written by Walton Cook

There’s a song by the great John Prine called “Hello in There” that consistently turns me into a blubbering mess when I hear it. In fact, I think it might legitimately be the saddest tune ever written. It’s about getting old and longing to connect with a world that seems to be only interested in keeping you at arm’s length on the best of days. Its chorus goes:

“You know that old trees just grow stronger

And old rivers grow wilder every day

Old people just grow lonesome

Waiting for someone to say, ‘Hello in there, hello.’”

THE AMUSEMENT PARK, the 1975 short film by George A. Romero that was released this year after being miraculously unearthed, feels like the nightmarish visual embodiment of that song. It follows the journey of a nameless old man played by Lincoln Maazel (who would go on the next year to play Cuda in Romero’s neo-vampire classic, MARTIN) as he attempts to navigate a day alone at a strange amusement park. The place basically chews him up and spits him out, as he is taken advantage of, harassed, or flatly ignored by nearly everyone he comes across.

The film is a series of unrelenting punches to the gut that affected me intensely. Maybe it was due to Maazel looking startlingly similar to my own grandpa (who was like a father to me when I was little), or perhaps it’s because becoming a dad has made me acutely aware of the passing of time thanks to every new pain and pop that erupts from my body each morning. Regardless of why, I know this much: the claim that this is one of Romero’s scariest films is no exaggeration.

COCKFIGHTER (1974)

Directed by Monte Hellman

Written by Charles Willeford

It took Monte Hellman passing away back in April for me to finally watch the copy of COCKFIGHTER that’d been sitting on my shelf for the better part of three years. Turns out waiting that long to see the infamous Hicksploitation classic was a mistake because let me tell you something: that right there is a damn fascinating film. It’s also one of the most stomach-churning pictures I’ve seen in a long time, so much so that I don’t plan on revisiting again. Weird, right?

At its core, the movie is your standard sports drama (complete with training montages) that follows the redemptive arc of a guy named Frank Mansfield (Warren Oates) as he attempts to claw his way back to the top of the pastime that consumes him. What’s absolutely surreal is that pastime is (as you may have guessed by now) cockfighting: a heinous and brutal game where two roosters are made to fight each other to the death while people gamble on what the outcome will be. As we follow Mansfield (who, by the way, speaks nary a word throughout the picture, having taken a vow of silence that will only be broken if he wins big again) we’re given a glimpse into an underground subculture that’s both repulsive and strangely mesmerizing.

There were several times when I almost turned COCKFIGHTER off. Hellman doesn’t pull any punches in the film and the rooster-on-rooster violence is something I found extremely difficult to see (incidentally, this is one of the few movies produced by Roger Corman that actually lost him money, so I don’t think I was alone in my discomfort). But like the best exploitation films, COCKFIGHTER draws you in, to the point where you couldn’t turn away if you tried. Whether it’s the outlandish nature of the story or the quality of the performances given by its stacked cast (the movie also features Richard B. Shull and a young Harry Dean Stanton), the film is one hell of an experience. For better or worse.

THE FRIENDS OF EDDIE COYLE (1973)

Directed by Peter Yates

Written by Paul Monash

A month or so ago I fell head-over-heels for Robert Mitchum.

The Criterion Channel had done up one of their nifty actor-focused collections spotlighting the dimple-chinned Noir legend, and over the course of a few nights it sank its claws into me quickly and thoroughly. Other than NIGHT OF THE HUNTER, I wasn’t all that familiar with his work, but I quickly realized that this was a leading man who was far more interesting than many of his contemporaries. Mitchum’s presence on the screen is calmly commanding, oozing a coolness that’s deceptively nonchalant while giving off hints of complexity just below the surface. Through films like THE BIG STEAL, TIL THE END OF TIME, and OUT OF THE PAST, I gained an increasing admiration for this weirdly handsome fella with eyes that somehow appear simultaneously amused and deeply sad.

But the picture of Mitchum’s that keeps coming to mind since that mini-marathon isn’t any of those 1940s classics, but rather, one he did nearly thirty years later. THE FRIENDS OF EDDIE COYLE is a gem of the American “New Hollywood” movement; a tight little crime drama centered around an aging small-time Boston hood named Eddie “Fingers” Coyle (Mitchum) as he’s faced with the choice of jail time or becoming a police informant. It’s a movie about misplaced loyalty and the regret you deal with when decisions from your past permanently alter your future. Mitchum gives a beautiful performance, breathing a pathos into the title character that never feels overplayed or melodramatic. His worn-down, hound dog features nakedly display the weight of the consequences he’s brought upon himself and the sense of hopelessness that’s enveloped him.

There’s a scene near the end of the film where Coyle and a friend of his are at a hockey game watching the Boston Bruins play. Eddie marvels at their star player (the legendary Bobby Orr, then a 24-year-old hotshot) and wonders aloud what it would be like to be young again. “Geez, what a future he’s got, uh?” he asks nobody in particular. It’s a quietly devastating moment, made all the more effective by the humanity Mitchum brings to the character, and it’s what makes his fate so haunting in the end.

FULCI FOR FAKE (2019)

Written and Directed by Simone Scafldi

FULCI FOR FAKE has one of the strangest setups I’ve ever seen in a documentary. It follows Italian actor Nicola Nocella as he tracks down and interviews friends, family, and former collaborators of the late “Godfather of Gore,” Lucio Fulci. He’s trying to get to the core of what made the man who he was because Nocella is set to play the legendary director in the first ever biopic to be released about his life. Only, as far as I’ve been able to tell, there is no biopic in the works: it’s a fictional narrative that’s used as a framework for the documentary as a whole.

This, as it turns out, is an ingenious idea. Not only does it give the overall picture a distinctive tone and freshness that sets it apart from other similar chronicles, but it reflects one of Fulci’s own key characteristics in that he understood inherently how one can mold the legend that surrounds them. This isn’t the kind of documentary that breaks down, picture by picture, a director’s filmography. Instead, it’s a portrait of a complicated man who also happened to be one of the greatest genre filmmakers of all time, and how instances in his life directly impacted his work.

Interestingly enough, what I keep coming back to when thinking about this documentary isn’t Lucio himself but his daughter, Camilla Fulci. She’s interviewed extensively throughout, and the candidness in which she speaks of both her personal and professional relationship with her dad (she worked closely with him on many of his films) is deeply affecting. Camilla is an intensely strong woman and her story, which is fraught with hardships, is the heart of FULCI FOR FAKE.

LOCAL HERO (1983)

Written and Directed by Bill Forsyth

I stopped looking for silver-linings in the pandemic long ago. This virtually unending nightmare has taken away too much and continues to leave scars I’m unsure will ever fully heal. But if you held me at gunpoint and told me to find one single thing related to Covid-19 that’s “good,” it’d be this: it’s injected a level of urgency into my life I didn’t think was possible. Suddenly realizing that tomorrow is not guaranteed does that to a person, and it’s made the idea of losing precious years to an unfulfilling job feel far more unacceptable than it did before.

That shift in thinking was on my mind when I watched director Bill Forsyth’s trademark film, LOCAL HERO. It’s a gem of a picture about a career-driven young businessman named Mac (Peter Riegert) who is sent to a village on the coast of Scotland by his Texas oil tycoon boss (Burt Lancaster). His mission is to find out what it would cost to get the entire community to relocate so that a refinery can be built where their ancestral home currently stands. Negotiations are going well (the majority of the villagers, craving more metropolitan lifestyles, are secretly attempting to fleece the wealthy Americans for all they’ve got) but the picturesque hamlet, its raw natural beauty, and the easy-going lifestyles of its inhabitants soon cause Mac to not only question the morality of its demise but his own life’s priorities as well.

“Quirky” is a word that’s been attached to LOCAL HERO often, sometimes in a dismissive sort of way, as if it coasts on surface charm without actually having anything to say. But there’s a lot going on in the film, it’s just not all that interested in whacking you over the head with it. The fragility of the natural world, the absurdity of capitalism, and the shifting meaning of home in modern society are all ideas it explores. However, it’s more concerned with getting people to think about the questions that stem from these themes rather than providing answers for them.

I finished LOCAL HERO with one sentence on my mind: life’s too short. That’s a thought I think many of its characters are grappling with, from Burt Lancaster’s bat-shit oil magnate to the humblest of the village’s residents. I have no idea what the next few years are going to bring, but I’m going to try my damndest not to forget those three words again.

LUCKY (2017)

Directed by John Carroll Lynch

Written by Logan Sparks and Drago Sumonja

Infinitely better writers than I have trumpeted the importance of Harry Dean Stanton, so I know there’s not much new I can bring to the conversation surrounding the acting legend. All I can say is this: I miss him and firmly believe that the world is a little less interesting since he left it.

LUCKY, Stanton’s final role and the directorial debut of actor John Carroll Lynch, was a film I put off watching for a long time. Centered around a fiercely independent 90-year-old atheist coming to terms with the fact that his death is essentially just around the corner, something about the picture cut a little too close to home for me. I’m sure part of it was my own crippling existential dread, but there was more to it than that. Stanton had died shortly after filming the movie, and the idea of watching a document of his last artistic moments on earth felt weirdly frightening to me.

However, this year I finally sat down to watch it, and I’m not ashamed to say that more than a few tears were shed. It’s a beautiful picture; a soulful contemplation of life, the relationships we make along the way, and how ends are just as natural as beginnings. Stanton’s performance is honest, brave, and intensely funny. While watching him, I couldn’t help but think of the last days of David Bowie and Leonard Cohen. Facing the great uncertainty of what comes next, Stanton did exactly what those two legends chose to do with their remaining time among us: He made great art.

MIKEY AND NICKY (1976)

Written and Directed by Elaine May

Sometimes a moment in a film can hit you so hard emotionally that it leaves you dazed afterwards. I had that experience with the opening scenes from Elaine May’s MIKEY AND NICKY, a movie about the friendship of two long-time friends/small-time crooks and what comes to light between them when the latter runs afoul of their mob boss employer. What we get in our introduction to the title characters (besides a masterclass in acting from its two legendary leads) is a depiction of male friendship that was rarely seen in movies at that time, let alone today.

Mikey (Peter Falk) arrives at the hotel room in which Nicky (John Cassavetes) has all but barricaded himself into. His childhood pal is in an extreme state of paranoia, so much so that he holds Mikey at gunpoint when he first enters the room. He’s convinced that the mob has put a hit out on him and is agitated to the point where he can’t decide whether his friend can be trusted. Mikey, for his part, possesses the calm of a man who’s familiar with both having a gun aimed at him and the distressed condition Nicky is in (we find out later he’s even predicted correctly that his friend’s ulcers are flaring up, and has come prepared with medicine for him).

Quietly, Mikey urges Nicky to lower his weapon. Then, in the same way a parent might attempt to comfort an upset child, he takes him by the shoulders and gently pulls him into an embrace. Nicky crumbles, sobbing into his friend’s neck while allowing his fears of being marked for death to spill out in a series of broken sentences. Mikey leads this trembling mess over to his bed and proceeds to force him to take his ulcer meds, all the while speaking to him with the soft but firm tones of a brother taking care of a sibling.

We tend to think that we’ve outrun many of the stereotypes surrounding masculinity and male friendships, but it’s still so common to see depictions in media that reinforce the outdated ideas that affection and vulnerability between men is (to use a suitably immature word) “icky.” To see the relationship between two mafia toughs in a picture made over forty years ago display these qualities is pretty damn surprising, and the scene adds so much more power to what the film eventually builds to with its climax.

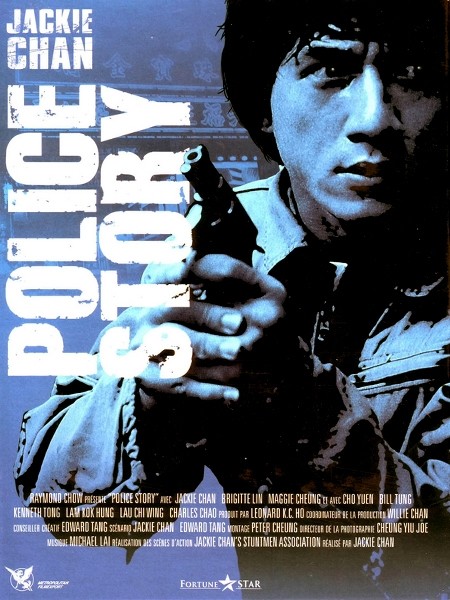

POLICE STORY (1985)

Directed by Jackie Chan

Written by Jackie Chan and Edward Tang

Jackie Chan is a true anomaly in the pantheon of action movie superstars. His performances strike a strange balance between extremes not typically seen in the genre. Chan is intensely goofy but low-key cool; heartwarmingly-clumsy yet jaw-droppingly precise; disarmingly gentle one moment and a human wrecking ball the next. On top of all this, he’s devoid of the machismo seen in so many of his peers, which is perhaps why he’s aged so well while others feel like relics of a masculinity that’s becoming increasingly outdated.

I grew up watching Jackie in films like RUMBLE IN THE BRONX and RUSH HOUR, but didn’t have access to any of his earlier work as I was basically at the mercy of whatever was showing on cable at the time (ahhh, the ’90s). However, this year I finally rectified that injustice by sitting down to watch POLICE STORY, a film that’s consistently ranked as one of Chan’s best and is apparently the actor’s personal favorite. What happened next was maybe the most purely entertaining movie-watching experience I had all year.

Chan (who’s other credits on the film include director, co-writer, stunt coordinator, and singer of its certified-banger of a theme song) seamlessly blends action and comedy with an ease that’s startling. His physicality has been described as a cross between Buster Keaton’s (who he’s acknowledged as an influence) and Bruce Lee’s (Jackie actually worked as a stuntman on ENTER THE DRAGON and FIST OF FURY), and nowhere is this more evident than in POLICE STORY. The grace he displays in both areas is incredible, and his toughness… good god, his toughness! Schwarzenegger and Stallone (legends, to be sure) may have had bigger muscles, but it’s hard to believe they could endure the levels of punishment Jackie did on a regular basis. And with a smile, no less!

STRAY DOG (1949)

Directed by Akira Kurosawa

Written by Ryûzô Kikushima and Akira Kurosawa

I remember hearing someone describe THE TEXAS CHAIN SAW MASSACRE as a film so visceral, you could practically smell the world being projected on the screen. Anyone who’s watched it can attest to the accuracy of that observation: the heat and humidity that radiates from the world Tobe Hooper creates is as sickeningly uncomfortable as a bead of sweat rolling down your spine. It makes you feel like you’re in the events playing out in front of you rather than just witnessing it, and those mind tricks are just as effective today as they were nearly 50 years ago.

Up until this year, I didn’t think another movie could affect me physically like CHAIN SAW did. Then came the dreary winter morning when I sweated through Akira Kurosawa’s noir drama, STRAY DOG. Set in 1940’s Tokyo during a heat wave, the story follows a young detective named Murakami (played by legendary badass/hunky boy Toshiro Mifune) as he attempts to track down a thief who has stolen his service weapon. Matters are further complicated when the hood begins gunning down people, adding to the cop’s desperation to redeem himself.

I’m sure it sounded like hyperbole when I wrote a second ago that I “sweated through” this movie, but I assure you it wasn’t. Maybe it was some undiagnosed medical issue ailing me that day, but I’m certain I was experiencing a psychosomatic episode brought on by the uncanny way Kurosawa is able to replicate the claustrophobia that comes with intense heat. It’s unescapable; surrounding Murakami and pressing upon him mercilessly like the guilt that engulfs him the longer he is unable to locate his perp. STRAY DOG, like the air on a scorching summer afternoon, has a weight to it that is undeniable.

When the film was finished, I remember stepping outside into the chill of that January day and breathing in the cold like a man who’d spent too much time in a sauna. In a way, I had.

THE VIGIL (2021)

Written and Directed by Keith Thomas

I watched THE VIGIL twice in one day. Not since I was a kid, riding high on the novelty of possessing a VCR for the first time but only having one tape to put in the contraption (it was Tim Burton’s BATMAN, if ya’ll are wondering) have I gotten to the end of a film and decided to go for seconds immediately afterwards. But like the movie’s terrifying parasitic demon, writer/director Keith Thomas’s tense and deeply moving story gripped me like a vice and refused to let go.

In it, a young man named Yakov Ronen (Dave Davis) is asked by his former Rabbi to be the Shomer for a deceased member of the Orthodox Jewish community he’s recently left. It will require him to sit with the man’s body until dawn and, in dire need of cash, Ronen reluctantly accepts. What he doesn’t know is that a dark entity known as a Mazzick was attached to the corpse he is now watching over. The demonic presence seeks out those who have suffered deep trauma and feeds on their pain, dooming its host to a lifetime of suffering. Housing a hidden anguish of his own, Ronen is faced with the choice of coming to terms with his past or becoming the Mazzick’s next victim.

THE VIGIL is thematically rich in a way few horror films can achieve without feeling either bloated or heavy-handed. It’s a film about spirituality, its ties to our identity, and all the difficulties that can come with that; it’s an examination of trauma, guilt, and the crippling way those two can feed off of each other; and it’s a painfully accurate portrait of grief and all its facets. All of this is anchored by its incredible lead who gives a beautifully nuanced performance that’s both heartbreaking and relatable. I felt instantly invested in the character of Yakov Ronen, which made the trials he endures throughout the movie all the more terrifying.

And make no mistake, THE VIGIL is terrifying. Its atmosphere is palpably oppressive thanks to the close confines of its setting and the way in which shadows are used to instill the creeping menace of the Mazzick’s growing presence. Jump scares are used sparingly, but when they are deployed, you’ll be lucky not to yelp out loud in fear (I may or may not have woken up my family after the payoff to one particularly tense setup). Finally, though we only see a few fleeting glimpses of it, the design of the Mazzick is infinitely creepy and easily one of my favorite creatures of the year.

Tags: Action Film, Akira Kurosawa, Arthouse, Bill Forsyth, Blu-ray, Burt Lancaster, Charles Willeford, comedy, Crime, Dave Davis, Denis Lawson, Drama, Elaine May, Fabio Frizzi, Fred Melamed, George A. Romero, Harry Dean Stanton, Horror, Jackie Chan, John Carroll Lynch, John Cassavetes, Keith Thomas, Lincoln Maazel, Lists, Lucio Fulci, Maggie Cheung, Menashe Lustig, Monte Hellman, Nicola Nocella, Peter Boyle, Peter Falk, Peter Riegert, peter yates, Robert Mitchum, roger corman, Ron Livingston, Simone Scafldi, Suspense, Takashi Shimura, Toshiro Mifune, Western

![The Amusement Park - Official Trailer [HD] | A Shudder Exclusive - YouTube](https://i.ytimg.com/vi/mLw_CYP02lg/mqdefault.jpg)

No Comments