When we talk about certain types of cinema, there is a tendency to omit contemporary critical analysis. This isn’t usually done out of malice; for many low-budget or genre films, contemporary reviews can be difficult to locate (if they ever existed in the first place) outside of weekly recaps or display ad blurbs. This does not disguise, however, the urge to gently nudge the narrative towards familiar territory. The giallo is now synonymous with cheap, populist cinema; referencing critics from film journals and The New York Times – and seeing them praise the talent involved – slightly undermines the points we try to make about these films.

It flatters us to think of genre films as overlooked items that require our more refined sensibilities to understand, and many movies do benefit from a bit of distance. What impresses me most about contemporary giallo reviews, though, is how accurate they seem even today. I cannot argue with critics’ scoffing towards the plots of a specific giallo, nor can I fault Gene Siskel for his shrugging dismissal of all Dario Argento narratives. These reviews are also quick to praise the directors involved for their striking use of visuals, and the compliments seem only slightly back-handed

What these reviews do best is provide is an opportunity to examine the two biggest names in the Italian giallo – Mario Bava and Dario Argento – and see if the reception of some of their earliest work compares favorably to their established reputations. What follows are a handful of contemporary reviews of both BLOOD AND BLACK LACE and FOUR FLIES ON GREY VELVET and my thoughts on how they’ve aged.

BLOOD AND BLACK LACE (1963)

“A field day for Bava fans (menace, mist, a body in the bath, red filters everywhere); others will find the whole thing faintly ridiculous.” (Sight and Sound, 1966)

“Murdering mannequins is sheer, wanton waste. And so is BLOOD AND BLACK LACE, the super-gory who-dunit, which came out of Italy to land at neighborhood houses yesterday sporting stilted dubbed English dialogue, stark color and grammar-school histrionics.” (New York Times, 1965)

“The blood motif is lovingly underscored by not only telephones but drapes, window dummies, finger-nails and lights. Colour and décor play their part in establishing a menacing, violent atmosphere that owes less to conventional tricks—creaking, storm-tossed shop signs, a dead body in a bath—than to ordinary things freshly observed, notably the burning of a diary in a fire, with great flecks of paper ash floating about in the hot air.” (Monthly Film Bulletin, 1966)

If you were to only read contemporary reviews of BLOOD AND BLACK LACE, you might be excused for thinking you know everything there is to know about the giallo. This small sampling already touches on several of the key aspects of the genre: it is derivative, primarily director-driven, and thrives on its visuals and strong use of color. And while each review seems happy to link Mario Bava to cinematic excess, the nature of this link has changed over time.

In retrospect, the violence in BLOOD AND BLACK LACE is both better and worse than contemporary reviews suggest. The gore in the film certainly has not stood the test of time; Bava’s small flourishes of blood and makeup are no match for the flayed dogs of Lucio Fulci’s A LIZARD IN WOMAN’S SKIN or even Bava’s subsequent impalements in the 1971 giallo TWITCH OF THE DEATH NERVE. However, the uncomfortable blend of the film’s vibrant style with constant violence towards women makes BLOOD AND BLACK LACE something of a horror-anachronism. The film aspires to the aesthetics of Hitchcock but has a cruel streak that feels, perhaps unfortunately, years ahead of its time.

A lot of the information contained in these also reviews speaks to the cult of the director that was already established around Bava. The Sight and Sound article specifically speaks to Bava as having his own fans – with the implication being that they existed as a subset of horror fans in general – that would see his films regardless of content. While most are fond of describing the genre of horror itself as the star, Bava was regarded as one of the first true horror auteurs, with an influence on cinematography that traveled internationally. Even when critics did not enjoy his films, they certainly recognized their appeal; each of the aforementioned reviews speaks to an audience for BLOOD AND BLACK LACE that just happens to not include that critic.

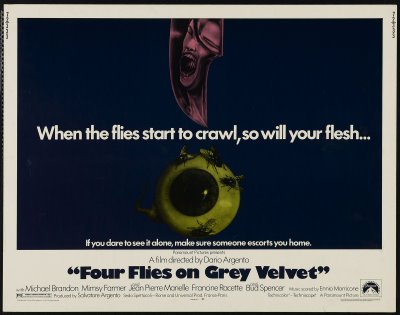

FOUR FLIES ON GREY VELVET (1971)

“It has striking, imaginative color photography and deep-freeze pacing and atmosphere. But they’re simply not enough, even in such a classy, handsome production.” (New York Times, 1972)

“The trouble with Argento, who certainly has visual flair and imagination, is that he has become so preoccupied with bravura stylistic flourishes, the grisly fetishes and techniques of his homicidal maniacs and the gimmickry upon which his stories turn that he neglects completely plot and characterization.” (Los Angeles Times, 1972)

“All of Argento’s films (THE BIRD WITH THE CRYSTAL PLUMAGE played here last year) pretty much look the same: Slick male and female model types walking thru chrome and glass apartments with the threat of stabbings permeating the air.” (Chicago Tribune, 1972)

There is an interesting tension between individual gialli and the quality of the genre as a whole. Taken out of context, most gialli are easy to dismiss, replete with meaningless red herrings and poorly dubbed English dialogue. As you string viewings together, however, a kind of internal coherency begins to emerge. Films like Argento’s FOUR FLIES ON GREY VELVET, which struggle in comparison to high polish Hollywood crime films, are elevated to a place of grandeur. We ignore troublesome production elements in favor of the wealth of purely visual information contained in the giallo.

And Dario Argento provides a lot of purely visual information.

During the opening credits for FOUR FLIES ON GREY VELVET, Argento introduces us to our nominal protagonist, the self-involved Roberto. In a series of intercut events, we watch as Roberto rehearses with his band and dodges a shady individual on the streets of Rome. The sequence closes on Robert using his drum kit to kill a fly; the camera frames Roberto’s face between two cymbals as they close on the final note of the song. With the fly sufficiently crushed, Roberto smiles slyly to himself, pleased at what he’s done.

This one shot – lasting only a few seconds – contains a wealth of information. Most obvious is the connection between the fly and the titular flies on grey velvet; one review in particular described this scene as foreshadowing the ending “even to non-specialists in detective fiction.” Since the action also occurs on beat with the music, we can (correctly) infer that Argento will play with musical conventions throughout the film. Most importantly, however, is that this shot hints at a retaliatory action which eclipses the original event – the fly simply hovering around Roberto – but one that brings great pleasure to the perpetrator. The ultimate identity of the killer, perhaps not effectively set up in the narrative, is foreshadowed visually from the film’s first reel.

— MATTHEW MONAGLE.

- [THE BIG QUESTION] WHAT’S YOUR FAVORITE FEMALE ENSEMBLE IN MOVIES? - July 22, 2016

- [IN THEATERS NOW] THE BOY (2016) - January 24, 2016

- Cult Movie Mania Releases Lucio Fulci Limited Edition VHS Sets - January 5, 2016

Tags: Columns, Criticism, dario argento, Film Reviews, Giallo, Giallo Week, mario bava, Matthew Monagle

No Comments