In 1996, the movie SCREAM was released into theaters. With Kevin Williamson’s hip and meta script, and the old-school gravitas of director Wes Craven, SCREAM was seen by a lot of people as the kind of shot in the arm that the horror genre desperately needed. It was aware of its past and seemed willing to burn the genre down in order to define its future.

Problem is, while those people weren’t wrong, they also weren’t right.

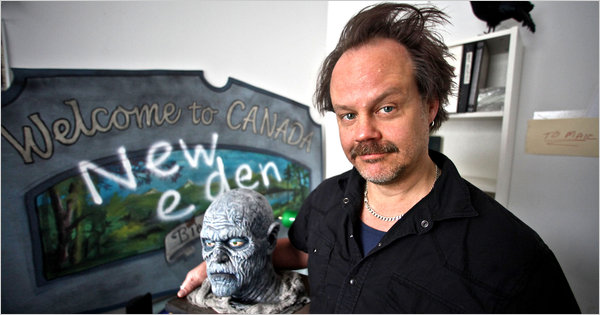

SCREAM is a great film, but its overall influence was far from positive, as it spawned a rash of imitators that seemed to believe SCREAM‘s success wasn’t its intelligence or its technical acumen, but its hiring of too-pretty teen stars of the moment and the kind of zeitgeist-chasing dialogue that feels old the second it takes to exit your mouth and hit your ears. What has become abundantly clear is that SCREAM was a prime representative of the nineties, not because it became a mission statement, but because like much of the quality genre fare of the decade, it was a one-off. As the years have gone by, though, there has been a slow buildup of quality films that take the tropes of the past and come at them in ways that are stylish, naturalistic, and emotionally devastating. However, this current trend hasn’t sprung out of nothing — in fact, the origin point for the current cinematic landscape in horror can be pinpointed to a single filmmaker. But that filmmaker wasn’t Craven, Romero, or even Carpenter — instead, it was a wild-haired New York City native with a broken smile by the name of Larry Fessenden.

This isn’t going to come as much of a surprise to those who are familiar with Fessenden and his work. In the last decade, he’s had a hand in films such as YOU’RE NEXT, HOUSE OF THE DEVIL, JUG FACE, STAKE LAND, LATE PHASES, THE BATTERY, and many more which would only serve as overkill to list here. Sometimes his contribution is only as an actor (or in the case of THE BATTERY, a voice over a walkie-talkie), but he’s had an even bigger impact as a producer, whose production company Glass Eye Pix effectively acts as a micro-studio which has produced genre defining work from writers and directors such as Ti West, Jim Mickle, Glenn McQuaid, and Mickey Keating. If we only counted those contributions, Fessenden’s influential nature would be without question, but it goes even further, because all of those films listed above, plus many more, are utilizing a cinematic language that Fessenden created with a series of films he made throughout the nineties.

Credit Fred R. Conrad/The New York Times

Fessenden’s most fertile period took place over a decade, with three films: NO TELLING (1991), HABIT (1995), and WENDIGO (2001). Collectively, they are referred to as his “Trilogy of Terror,” but individually they act as Generation X’s answer to FRANKENSTEIN, DRACULA, and THE WOLFMAN. These three films offer a very specific vision of how to tell a horror story, taking more cues from the nature-as-monster narrative of THE BIRDS than from proto-slasher stylings of PSYCHO as is the case with most of his contemporaries. Fessenden’s films take their time to build up their horror elements, to the point that the terror part of the trilogy could be seen as a bit of a misnomer, since if you go into these films cold, the first hour’s worth of material are usually very human dramas. If the New Hollywood ever made monster movies, they would look a lot like Fessenden’s films. Utilizing that era’s “everything old is new again” approach to genre, he digs deep into what makes us human, particularly when confronted with the monstrous.

Although not his first feature — that would be the virtually unfindable EXPERIENCED MOVERS— NO TELLING offers an interesting if unwieldy opening statement for Larry Fessenden’s approach to genre. The film centers on a woman named Lillian Gaines (Miriam Healy-Louie) spending a summer with her husband Geoffrey (Stephen Ramsey) in the country, both to get away from the city and for Geoffrey to work on an experimental limb-transfer surgery, away from prying eyes. While there, long-simmering martial problems come to a head,and Lillian meets an environmental activist named Alex Vine (David Van Tieghem), while Geoffrey continues to push his experiments into possibly unethical directions. The film looks great, as Fessenden utilizes the lush greens of the New York countryside to great effect. However, it’s probably Fessenden’s peachiest film. Fessenden has long been an activist for the environment and animals, and NO TELLING was made at the peak of his passion. (He even went so far to write a booklet on low impact filmmaking). The setting of the film in a rural farming community allowed Fessenden to really get into the problems of the day, with the Alex Vine character given long strings of dialogue about the dangers of pesticides. both to the environment and to the farmers who use it. Although still valid nearly twenty five years later. it doesn’t coalesce as well with the rest of the film as you would hope. Thankfully, Fessenden seems like he was aware of this enough that he manages to rein it in, so it never comes off as obnoxious.

The real meat of the story is in the form of science run amok, as represented by Geoffrey. Geoffrey’s research involves a lot of animal experimentation, starting with mice but eventually moving on to dogs and calves he acquires through various means around the community. Fessenden stages these scenes like serial killings out of something like HENRY: PORTRAIT OF A SERIAL KILLER — he makes it clear this is in the name of science, but there’s a casual cruelty to it that makes the whole thing feel sick. Fessenden uses that cruelty to make a broader point about the causal nature of how human beings can treat the world around them, and also for how as a people we really don’t want to know the great details of what goes into scientific progress. These points combine as Lillian begins to learn to live alongside nature while spending time with Alex, and while she comes to realize that Geoffrey only sees the natural world as a means to an end, ultimately leading him to create something completely unnatural in the climax of the film. In the world of NO TELLING, humans might not be monsters, but our ambitions might just create some.

NO TELLING is a solid film, but it’s a bit slow going, and pretty much the definition of minimalist horror. As engaged as he might be, you can kind of feel Fessenden rubbing up against the parameters of the story and setting. So it’s interesting that he went from the naturalistic painted polish of NO TELLING to the grainy guerrilla style he utilizes in HABIT.

HABIT is an interesting film in the Fessenden oeuvre given its setting, its shooting style, and the personal touches from Fessenden’s own life and struggles that blur the line between fact and fiction. Doubly so in the fact that Fessenden himself plays the lead.

At this point, it’s worth noting that Fessenden the director and Fessenden the actor have always been fairly separate entities. Despite having a few early successes, including being the male lead in Kelly Reichardt’s now classic RIVER OF GRASS, Fessenden has never used his films as a showcase of his own acting a la Ed Burns or early Spike Lee. He has small roles here and there in films he’s produced, but it’s not so much nepotism and more just being the right man for the job. Of the movies he’s directed, it’s more likely he’ll have a stand in for himself, as with NO TELLING‘s Alex Vine, in roles wic he just hands over to other actors. Fessenden never assumed he would play the lead in HABIT, going so far as to hold several casting sessions, but it makes sense he did, since Fessenden’s character in HABIT isn’t so much a stand-in as he is a very specific version of Fessenden himself, which includes his own real life story of how he lost his front tooth in a mugging, to his past with self-harm and self-medication. It’s hard to imagine anyone else playing the role.

HABIT centers on Sam (Fessenden) in the wake of his father’s death and his breakup from his long-time girlfriend. He spends his days hanging out with friends and indulging in heavy drinking with a side of melancholy until he meets Anna (Meredith Snaider) at a Halloween party. They instantly form a connection and begin a very sex-driven relationship, which Sam indulges in the same way he does the drink. As time goes on, Sam’s mental state deteriorates, and he begins to suspect that Anna might be contributing to it in some way, eventually coming to the conclusion that she might be a vampire. HABIT is the film that has become the film most closely associated with Fessenden, both because of the autobiographical elements to Fessenden’s own life and because it’s basically his cinematic thesis statement.

NO TELLING can generally be described as an interesting oddity, but HABIT is a gauntlet being thrown down. Fessenden made the movie with a small crew, often shooting in the city with no permit,s and staging scenes on the quick with handheld cameras. There’s passion and danger that comes through nearly every frame, Fessenden showing just like many other independent filmmakers of the time that if you want to make a movie, than there’s really no other choice but just to make it. In the case of HABIT, Fessenden had access to a culture of New York city bohemia very rarely caught on film, as well as a wealth of personal experience as an artist just trying to live another day in a city that’ll eat you whole given the chance. And that hunger is brilliantly personified by the sexual relationship between Sam and Anna.

The sex scenes in HABIT aren’t the sort of thing that would make Lars van Trier blush, but even in a modern context it’s still impressive both in how much they show and in how they actually contribute to the film aside from baseline titillation. Sex in HABIT says a lot about its characters, Sam using it as another form of medication to avoid pain, and Anna as the aggressor and dominating in a way that telegraphs a predatory nature that only fully becomes apparent as the film goes on. The relationship is disturbing enough when taken from a strictly human point of view, and when the supernatural elements are fully introduced late in the film, it’s just icing on the cake. Fessenden offers a look at a familiar relationship dynamic that doesn’t operate on love but on something close — it’s the sort of connection that only really forms when you’ve gone through that special hellish blend of death, disappointment, and heartache that leads you to someone you can lose yourself in but who will ultimately tear you apart. By the time the idea that Anna might be a vampire appears, Fessenden has made us watch Sam just deteriorate right before our eyes, and like his friends, we have no way of knowing if what he’s seeing is real or if it’s the rambling hallucinations of an addict in the middle of a mental breakdown.

Those elements of whether or not what we are seeing is “real” is very important in Fessenden’s films. NO TELLING had small elements of it, and HABIT goes even further, but Fessenden perfects it with WENDIGO. Seeking a short winter vacation in rural winter New York, George (Jake Weber), his wife Kim (Patricia Clarkson), and their young son Miles (Erik Per Sullivan) get into a car accident by hitting a deer that was being pursued by local hunter Otis (John Speredakos). George and Otis instantly take a disliking to one another, particularly after Otis shoots the injured deer right in front of Miles. Afterwards, they head to their rented cabin, but Otis continues to taunt them over the course of the next day, until suddenly tragedy strikes, and an ancient spirit makes itself known. Like NO TELLING and HABIT, WENDIGO takes its time to reveal itself as a horror movie, and it uses the majority of its run time on a meditation of the differences of modern masculinity and on the kind of love/hate relationship that only exists between father and son. George represents the kind of guy that doesn’t have anything to prove except when he runs up against a guy like Otis, someone who inhabits an antiquated but for some reason idealized version of what a man is, and the frustration that goes along with it.

We see that frustration play out through Miles’s point of view, which adds WENDIGO‘s final layer with Fessenden’s particular brand of horror of the mind. In NO TELLING, the horror literally springs from Geoffrey’s mind, while in HABIT, there’s more than enough evidence in the final minutes of the film that seem to suggest that Anna’s vampirism could possibly all be in Sam’s head, but WENDIGO is filtered through the eyes of a scared child, who turns Otis and his version of toxic masculinity into a literal monster in his closet. So when that particular monster unleashes itself further into Miles world by fatally attacking his father, that’s when the titular monster of the film finally makes its appearance.

The WENDIGO has become a fairly well known Native American myth in recent years, to the point where it’s become a prominent X-MEN villain, but the gist of it is that its a spirit that was formerly a man who engaged in cannibalism and is now cursed with a beastly form and an insatiable appetite. Fessenden retains that aspect but also interprets it in his own way, even going so far as to provide voiceover himself, in a scene where Miles is told the legend in the first place by a local Native American man when the actor couldn’t deliver his lines, making this version of the WENDIGO Fessenden’s own, as a shapeshifter who takes on the form of a skeleton made of tree branches to a more traditional flesh and blood monster that eventually seeks out Otis as a kind of spirit of vengeance. The way it goes after Otis has the kind of fury that only a child could muster, which makes you wonder if the WENDIGO actually exists, or if it’s just something Miles is imagining to create a kind of karmic balancing system to make sense of this tragedy. WENDIGO caps off Fessenden’s first decade of professional filmmaking with no easy answers and the unsettling feeling that outside man’s petty struggles, nature endures with an unblinking gaze.

The idea of nature enduring comes into play again with Fessenden’s next feature, THE LAST WINTER (2008), which drops a lot of the build-up elements of the Trilogy of Terror and goes for a much more straightforward approach in its telling. When Ed Pollack (Ron Perlman) returns to his Alaskan outpost, where he’s trying to set up infrastructure for oil drilling, his crew informs him that his second-in-command Abby (Connie Britton) has begun seeing the station’s ecological advisor James (James Le Gros), who in turn believes that the impact of the drilling will cause irreversible damage. As they argue, the crew begins experiencing odd phenomena around the station, and it soon becomes clear that an otherworldly presence is making itself known.

THE LAST WINTER plays like Fessenden’s attempt at a ghost story, a la THE AMITYVILLE HORROR, where the haunted house infects its inhabitants with a madness that moves like a virus. The only difference is that the haunted house in this story is the world itself, and like a lot of haunted houses, it wants its residents out of it. THE LAST WINTER doesn’t have the same intimacy that Fessenden’s other films have, but it has environmental passions present of the sort that got him started in NO TELLING. However, whereas NO TELLING had a modicum of hope that we could turn our relationship with the natural world aroun,d THE LAST WINTER has none of that. Fessenden has been watching too long, and although the words “global warming” are only mentioned once, he knows that the writing is on the wall. There is no respite, with the potential that the horror we’re seeing is not real in the world of the film, and as such, Fessenden ostensibly created a film that acts as an elegy for humanity.

If that comes off as depressing, that’s because it is, and you get the feeling that coming off THE LAST WINTER, Fessenden’s priorities had shifted. It’s immediately following this film that his work as a producer went into overdrive, and he began popping up in more acting roles. It’s possible given that his own films hadn’t hit much farther than cult status by this point, that he felt that he could do more good utilizing what he had learned working within his own independent productions to ensure that some younger filmmakers could have an easier go than he did. And if those younger filmmakers just happened to start out as Glass Eye Pix interns, or were directly influenced by Fessenden himself, all the better.

This isn’t to say he wasn’t pursuing his own projects at the time, most notably how he began working on an American remake of THE ORPHANAGE with Guillermo Del Toro that fell apart, and even tried petitioning Marvel for the rights for Werewolf by Night before they became a cinematic juggernaut and locked their shit down tighter than an axe murderer in an insane asylum. The main problem, though, seems to be that while Fessenden was proving himself with quality genre fare, he was still seen as a weird indie auteur that major studio people just assumed wouldn’t want to work for them, an understandable assumption but one that no doubt led Fessenden to bang his head against a few walls. So it wouldn’t be until 2013 that we would get what is at this time his most recent film as director, BENEATH.

Following a group of high school graduates Johnny (Daniel Zovatto), Kitty (Bonnie Dennison) , Matt (Chris Conroy), Simon (Jonny Orsini), Zeke (Griffin Newman), and Deb (Mackenzie Rosman) decide to take a final summer vacation at a nearby lake, but quickly discover that the lake is home to a giant man-eating fish that leaves them stranded in in the middle of the lake without a paddle on a slowly sinking boat. As they try to reach the shore, they start realizing that in order to distract the predator, they need to give it some bait, and proceed to vote each other out of the boat, which leads to long buried secrets and grudges being revealed.

From the outside, BENEATH looks like Fessenden’s most commercial film, in terms of structure and content, but working off a script he himself didn’t write, BENEATH plays like a strangely detached exercise for Fessenden. However, that might be to its benefit, and that subsequently allows Fessenden to work outside his wheelhouse and still manage to add his own little personal touches. The most obvious example of this being the giant man-eating fish, which is a practical creation that looks equal parts goofy and terrifying and yet weirdly endearing. It’s his take on THE CREATURE FROM THE BLACK LAGOON by way of JAWS and as such, it’s not the villain by any means, just a beast following its natural instincts. Instinct turns out to be the backbone of the film, because what follows is almost every human character indulging in their worst ones.

Films in secluded locations, inhabited by characters who turn on one another to survive, are a dime a dozen, but Fessenden is a savvy enough filmmaker to know what beats to hit and how to work with actors to create a series of very unique scenarios. The cast of BENEATH is a lot younger than those of most of his previous productions, and he uses that fact to show what characters would do if they believed they had to fight for the rest of their lives. The film is in line with the rest of his filmography because it works with the points he’s already made about the primal nature of the world, and BENEATH‘s characters are driven by primal desires like lust and self preservation, but ultimately it just comes down petty jealousies and each of them getting payback for petty grudges. They just happen to be using a giant fish to act out their resentments, and Fessenden cranks up the tension with every pass the fish makes and every drop of bloody water thrown out of their sinking boat until the very end, when the last man standing is left in the dark of the night, one monster being eaten by another.

Larry Fessenden has been working for over thirty years at this point, and he has shown just how far someone can go with a unique vision and perseverance. He hasn’t been ignored, rather in the world of horror and independent film he’s played the part of a patron and comes close to being seen as a saint in some circles, but it’s only recently he has been acknowledged as the trailblazer that he was and continues to be. Even outside of film, he continues to create new and daring narratives, whether it’s through the intensely creepy audio plays for the digital age Tales from Beyond the Pale, or the critically acclaimed choose-your-own-slasher-movie-style video game Until Dawn. Larry Fessenden isn’t done by any means, Glass Eye Pix is still going strong, and Fessenden will no doubt step behind the camera again in the near future, but as of right no,w he would be more than justified to sit back and look at a landscape that he has helped create. Fessenden’s legacy is ongoing, but of all of his contributions, his most notable might be offering the world films that brings humanity back to its monsters while making humanity itself look monstrous. Its Larry Fessenden’s world, and we’re lucky to be living in it.

— Patrick Smith.

NO TELLING, HABIT, WENDIGO, and THE LAST WINTER have recently been collected on Blu-Ray by the good folks at Shout! Factory via THE LARRY FESSENDEN COLLECTION. If interested, you can support Daily Grindhouse by buying it here and BENEATH here.

Tags: Blu-ray, Connie Britton, Glass Eye Pix, Glenn McQuaid, Horror, Jim Mickle, Larry Fessenden, Mickey Keating, Patricia Clarkson, Ron Perlman, Ti West

No Comments