John Krasinski’s latest cinematic endeavor, A QUIET PLACE, is a refreshingly strict take on the horror-thriller genre. Carefully crafted and meticulously structured, A QUIET PLACE is a film that relies heavily on its own premise without ever boasting its own brilliance. The script, co-written by Bryan Woods, Scott Beck, and Krasinski himself, plays hard by the rules, sticking to the fundamentals of both storytelling and technical cinematics. On paper, sticking to the basics seems like a lazy and uninspired decision, but Krasinski uses this precision to showcase his grip on a compelling narrative – eliminating the use of trivial subplots and almost-all cheap jump scares, while also utilizing subversion to keep audiences on their toes.

Manifested in its jaunt-of-a-runtime (only 90 minutes), A QUIET PLACE doesn’t wait around – exercising absolutely no narrative hesitation. The film opens on a title card that reads “Day 89.” It seems the entire world is a newly post-apocalyptic society with very few survivors of the dangers that have caused this catastrophe. Vicious predators lurk in the wild, but they only attack what they can hear, as they continuously use aural sensations to hunt. We meet an unnamed family slowly and quietly rummaging through an abandoned drug store looking for the right concoction of prescription medicine that will aid their son (Noah Jupe) – who presumably has a fever or flu of some sorts. The mother (Emily Blunt) carries her sickly son, while her other two kids – a deaf daughter (played by the noteworthy Millicent Simmonds) and a youngest son (Cade Woodward) – roam the store, silently looking at toys – a reminder that the joys of childhood are likely to be put on hold indefinitely. Using sign language, the father (John Krasinski) tells his family that it is time for them to get moving. The family’s use of sign language is the most logical explanation to their survival in their new world of silence. On their journey back home, the youngest son makes a critical – and yes, loud – error that results in a heartbreaking loss for the family. The family of five now becomes a family of four.

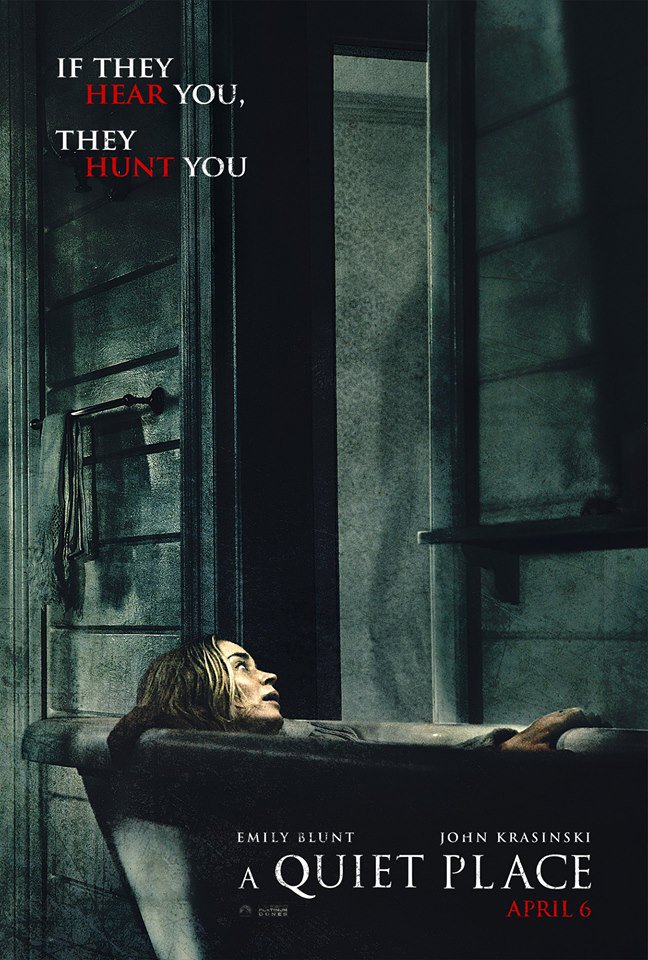

The rest of the film takes place about one year later on the family’s farm – composed of large cornfields and a few towering silos. While the monstrous beings are still at large, the family has found a rhythm of silent survival. Everything from how they cook their dinners to how they play Monopoly is redesigned to make almost no sound. We learn that the mother is pregnant, and nearing her due date. This is where the film becomes provoking: In a world where silence is required, is a life of fulfillment possible if it’s a necessity to be so cautious – and even bigger than that – how the hell do you deliver a baby into this world under these circumstances? Krasinski explores these ideas throughout the remainder of the film, investigating the human condition within the harshest of environments.

The most striking aspect of the film is the premise itself – it’s where the intrigue is rooted and it’s what makes the film widely palatable (I predict commercial success). The idea that the characters must remain quiet or die is one that inherently comes with a lot of tension and anxiety. The world of A QUIET PLACE is one that feels feverishly lived in, with an ever-present anticipation of terror. Any good horror-thriller films present situations that demand a lot from the characters in them. A QUIET PLACE is not only demanding to the characters but also to the audience. We feel the need to hold our breaths and remain silent just as much as the characters on screen do. Because of this, audience members become active participants alongside the characters, ultimately leading to a gripping cinematic experience. If there is any film for which you want to triple-check that your phone is on silent, it’s this one.

Of course, this cinematic manipulation is not by mistake. The film is pieced together superbly, allowing both the emotional beats and the frightening beats to land relatively on cue. From the smart use of parallel editing to the silently deafening sound design, Krasinski displays again and again his understanding (and emphasis) on the fundamental tenets of narrative structure. Never relying on a big ‘gasp’ moment, the story feels grounded. Themes of parental burden and blame are threaded through the film as subtext, giving it depth, weight, and a surprising amount of heart without feeling out of place or unwarranted. Performances from Emily Blunt, Millicent Simmonds, Noah Jupe, and John Krasinski are collectively praise-worthy – especially with almost no dialogue, a lot of emotion and character is conveyed through nuances in facial expressions, body language, and mannerisms.

If you’re wondering if the movie is scary at all, let me reassure you that there are moments of violence and terror that are both satisfying but not at all exploitative. The creature design is remarkably imaginative: a large looming, fast-moving creature whose face opens up to reveal massive fleshy ear-like caverns. It should be noted that the usage of the monster’s design is never overplayed, always furthering the story and allowing the audience and characters alike to discover something new.

While there’s a lot to like in A QUIET PLACE, not everything that is presented lands properly. At moments, the big ideas that appear posed to be explored get lost in the same kind of chaos that feels inherent to any horror film. Because of this, the film feels more frightening and thrilling than it does compelling. With its proper pacing and structure, A QUIET PLACE is most definitely satisfying and worthy of discussion, but feels a little too flat in terms of emotional impact. Regardless, A QUIET PLACE delivers on what it promises, offering a fun theatrical experience held together by a level of intelligence and prowess that is unfortunately rare to find in this genre.

Tags: Bryan Woods, Cade Woodward, Charlotte Bruus Christensen, Christopher Tellefsen, emily blunt, Horror, John Krasinski, Marco Beltrami, Millicent Simmonds, Monsters, Noah Jupe, Paramount Pictures, Platinum Dunes, Post-Apocalyptic Cinema, Scott Beck

No Comments