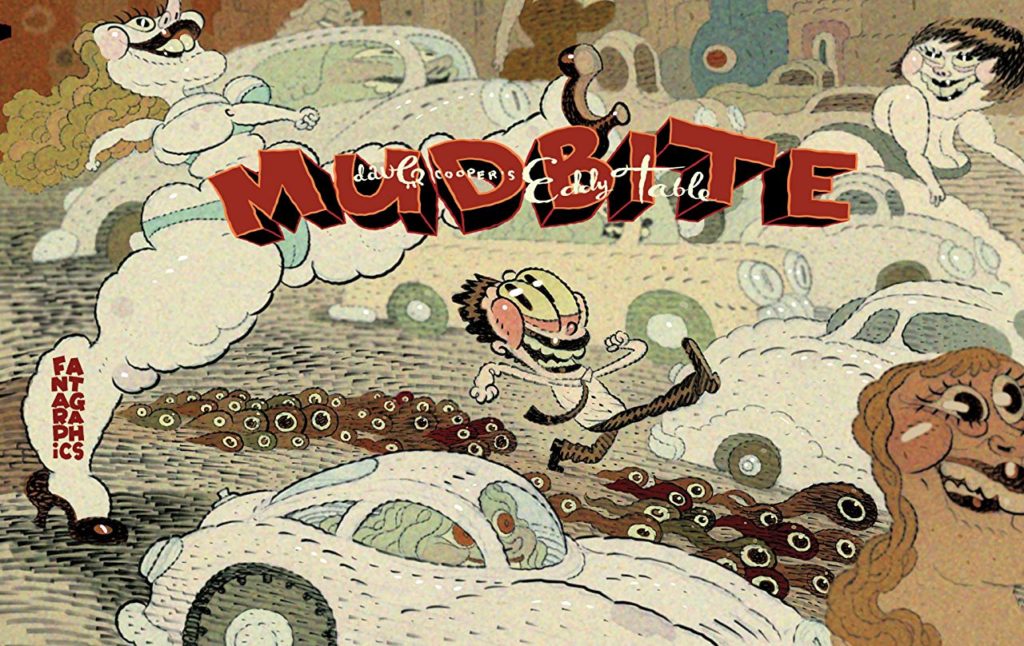

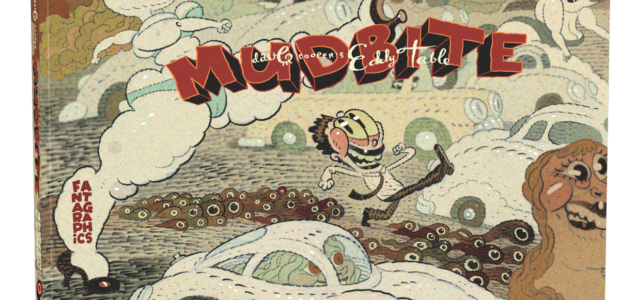

It’s been awhile — 15 years, to be precise — since seminal underground id-baring cartoonist Dave Cooper released a wholly original graphic novel, and while the length of his latest, Fantagraphics-published book, Mudbite, may make it more of a “novella” than anything else, the main thing is that Cooper has, indeed, returned to the fold, his alter-ego protagonist Eddy Table in tow, and that his work as just as singularly unsettling as ever, maybe even moreso. Prepare, then, to feel very disturbed by the things you’re capable of laughing at.

And you will laugh at Mudbite‘s two stories, “Bug Bite” and “Mud River” (now you know where the book’s title comes from), of that there is no doubt — but you’ll just as surely find yourself cringing, scratching your head, even needing to pick your jaw up off the floor on occasion. The biggest question you’ll probably be left with is “where does this guy come up with this stuff?,” but never fear, that’s where your handy armchair answer-man comes in: this is coming straight from Cooper’s subconscious, probably even his dreams. At least I hope that’s the case.

Most of our dreams, I’d wager, would come off as being seriously screwed-up to an outside observer, and for that reason there aren’t many of us who be either foolish or brave enough to transcribe them into pictures and words, but Cooper suffers from no such sense of propriety: like it, lump it, or loathe it, this is a warts-and-all look into the deeper recesses of one of the more idiosyncratic minds in contemporary cartooning — one with, it would appear, zero fucks left to give.

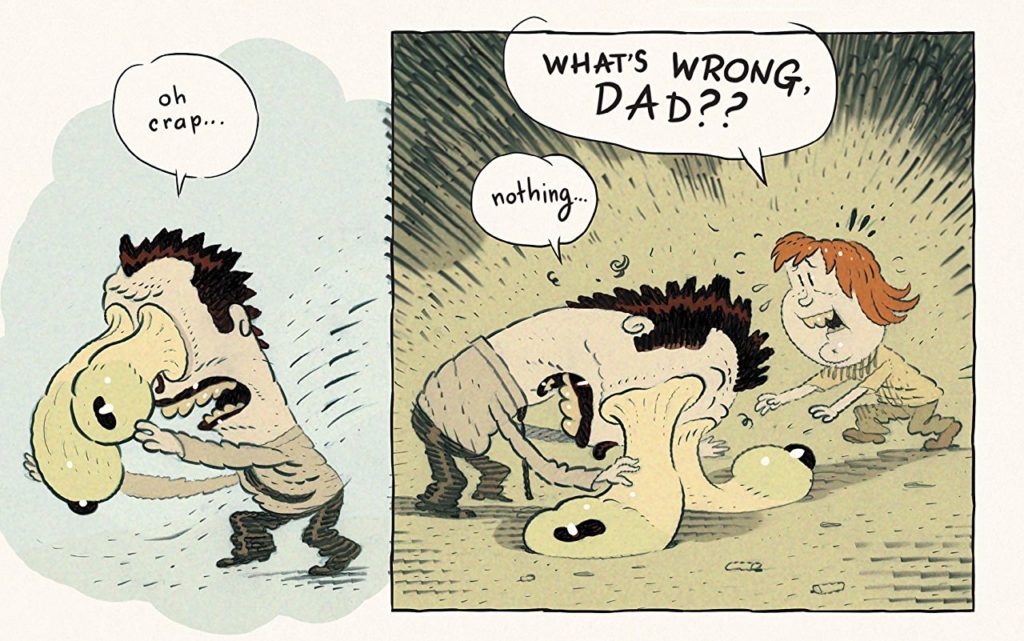

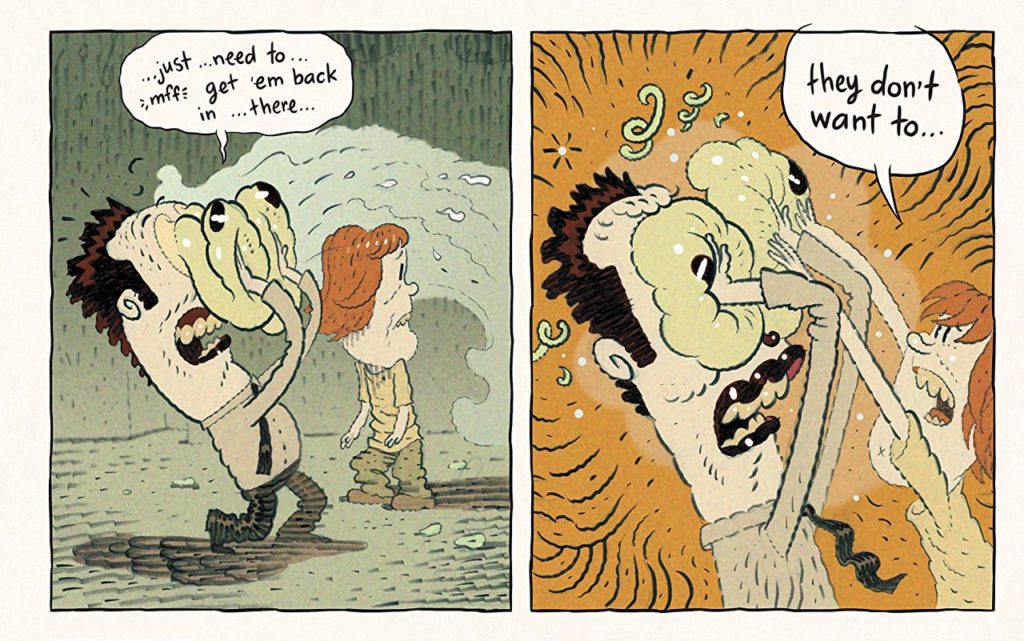

A family trip to a vice-laden big city is the bare-bones premise at the heart of “Bug Bite” while a rapidly-encroaching natural disaster forms the equally-basic backbone of “B-side” (the book is “flippable,” with each segment having its own cover) story “Mud River,” but both are cut from very much the same cloth and revolve around similar neuroses of guilt, shame, alienation from one’s own desires and authentic self, and fear — of being exposed as a “perv,” of losing impulse control, of blowing up an ostensibly happy domestic situation by betraying one’s spouse and/or disappointing one’s children — dreams have a way of exposing ourselves to ourselves, and it may just be that Cooper is on to something here: lay out your most bizarre and shameful fantasy scenarios in a public forum, and the things that fill your heart and head with misgivings about your own nature and character tend to lose their power to hinder, even cripple, you. After all, if everyone knows you want to go for a ride inside a giant woman’s butt-crack (yes, Coop — I mean Table really does that here), most anything else they learn about you is going to seem downright tame in comparison, and who knows? Some big, billowy, jiggly giantess with a generously-proportioned rump may even show up at your door and haul you off.

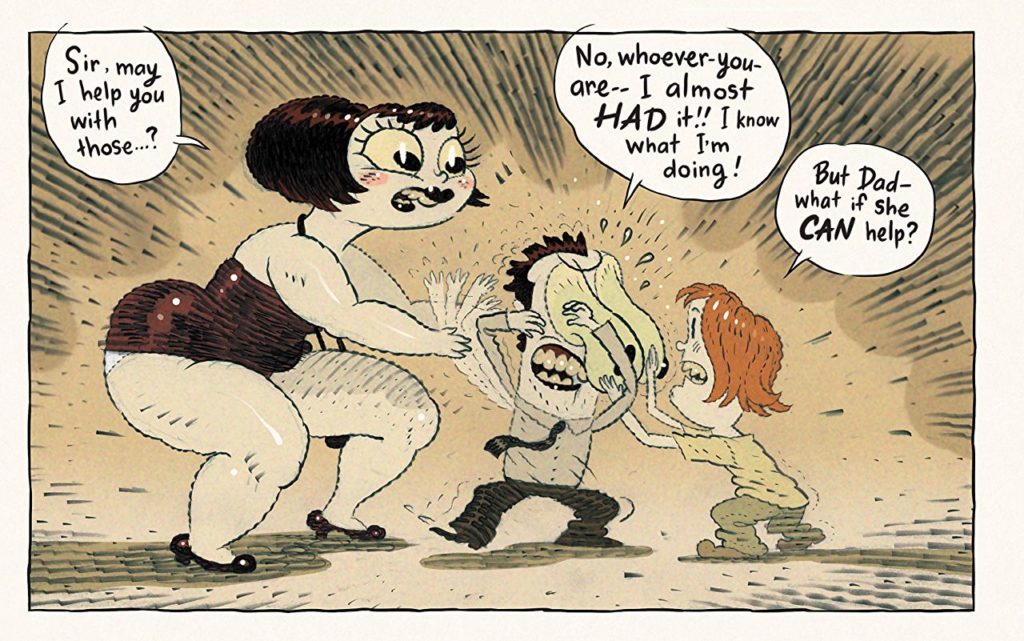

Ah, yes, those Cooper women — fleshy, cellulite-flaunting gargantuettes who dress like streetcorner hookers, torment the weak wills of men by dint of their very existence, and do it all with an entirely unforced obliviousness — they’re rather a problematic feature of his work, aren’t they? Cooper’s bodily fetishes seem to pick up more or less directly where Crumb’s leave off, and operate with at least as little regard for their subj — sorry, objects, since that really is all they’re treated as, if we’re being absolutely honest . The gal who gets Eddy to safety tucked inside her ass in “Mud River” is literally brain-dead for most of the strip, and the second her perceptive faculties and reasoning return, her utility is over, while in “Bug Bite” a woman (possibly an old flame?) of equally generous proportions exists solely to tempt him while his far-less-curvy wife is pictured as a well-meaning, if hopelessly naive, sort who probably does a fine job of tending to the home and raising the kids, but is a ball-buster by default simply because her presence in his life prevents him from chasing after the sorts of ladies that really get his motor running. The idea that anyone with a vagina might have a reason for her existence beyond either being a representation of all he can’t have or a reason for why he can’t have it doesn’t enter into the equation here at all.

To his (marginal) credit, at least Cooper doesn’t idealize the mindset he portrays his stand-in as inhabiting, but he’s not exactly critical of its de-humanizing implications, either: Table has been a self-indulgent cad with no control over his reactions to stimuli since way back in his first appearance in Weasel, and while he may have gotten older since then, he’s clearly none the wiser when it comes to bottling up the teenage horn-dog misogynist inside. His attempts to put on a brave face and/or solve the problems his that his weakness, lust, stupidity, and avarice cause invariably have entirely-foreseeable-to-all-but-him consequences — particularly true in the case of “Bug Bite,” which lays out a nonchalantly-delivered “whammy” of an ending — but being honest about your tendency to objectify and taking the authorial view that eschewing said tendency only leads to disaster is, at the very least, akin to saying “too bad he can’t just give in to each and every one of his darkest impulses, everything would work out so much better if he did.” Like I said, this book’s going to make you feel pretty damn uncomfortable in places.

The art mitigates that queasy sensation somewhat, of course: Cooper’s bold, exaggerated, hyper-kinetic style, rendered in lush and vibrant, though hardly garish, tones is about as “cartoony” as it gets, and definitely couches the blunt-force impact of the combustible subject matter, as does the warped “dream logic” of the proceedings (the hallway in a junk shop goes on forever and transitions into an outdoor locale filled with strange parasitic creatures as opposed to just, ya know, leading outside), but just because even a quick glance at this book betrays its obvious Jim Woodring influence doesn’t mean that he and Cooper have anything like the same sort of dreamscapes unfolding first in their minds, then through their hands (and drawing implements) and finally onto paper. There’s a seediness to both Cooper’s desires and environs that cause them to mirror — hell, amplify — each other, and while both cartoonists excel at depicting hermetically-sealed alternate realities that play by an internally-consistent set of unwritten, but intuitively understood, rules, there is charm lurking beneath Woodring’s fascinations, whereas Cooper’s make you feel like you need a shower after even less-than-prolonged exposure to them.

All of which means that Mudbite may not exactly qualify as “dangerous” imagining — to hell with Freud or Jung, any home-office therapist has probably heard objectively “worse” than Cooper delineates and expounds upon here — but transmitting material of this nature? Well, that could lead to some friction and turbulence at home, I shouldn’t wonder. We’re not in Joe-Matt-jerking-off-into-a-Kleenex-tissue territory here or anything, but that, at least, is relatively easy to relate to and speaks more to the garden-variety debauchery that the conscious individual is entirely capable of. Cooper, however, is far more concerned with emptying the contents of his subconscious, and as a result many of the scenarios we are privy to here, over-the-top and absurd as they may be (okay, are), really do cause you to hope that not too many guys go to bed at night and see these sorts of visions dancing behind their closed eyelids.

Still, good art is, by nature if not by definition, about illuminating what is typically obscured by shadow, and in that sense Cooper is carrying on a proud tradition — as well as cutting through the bullshit on a personal level. That doesn’t, of course, automatically mean that he’s adding something new to the conversation between artist and audience, nor that we’re in any way particularly enriched by his decision to throw open the curtains of his interior life and force us to look at what most, probably sensibly, hide from view. Hang-ups are a drag, sure — but as anyone who has spent time around somebody who loses all their inhibitions after they’ve had a few drinks can tell you, they do serve a purpose, in that they prevent us from having to learn more about an individual than we’d probably care to.

Dave Cooper is a guy you can get to know more than a bit too well through his work, and so for that reason Mudbite, which is probably his most in-depth look at the contents within his own mind yet, will hold a lot more appeal to those who tend to listen to, even engage with, the guy who treats the barstool like a confessional rather than those who move down to the end to get the hell away from him and enjoy their drink in peace. As a comic, then, its virtues are probably relative to the individual who happens to be reading it. As an act of “art therapy,” though, it’s efficacy — for good, ill, or a little of both — is absolutely undeniable.

Tags: Columns, Comic Books, Comics, Dave Cooper, Fantagraphics

No Comments