HENRY: PORTRAIT OF A SERIAL KILLER famously (or perhaps infamously) languished on the shelf for over three years after its festival premiere in 1986. Deemed too revolting in its graphic depiction of sex and violence, the MPAA insisted that no amount of editing could earn director John McNaughton an R rating, making it a tough sale to distributors wary of the dreaded X rating. Its eventual release — and the 30 years since — did little to dilute HENRY’s soul-searing power: it remains the sort of movie you can stomach only occasionally, and it certainly isn’t comfort food. Maybe this was the thinking behind SKINNER: with HENRY being so difficult to digest, why not offer the same thing, only with heaping helping of nonsense to make it go down more easily?

The movie:

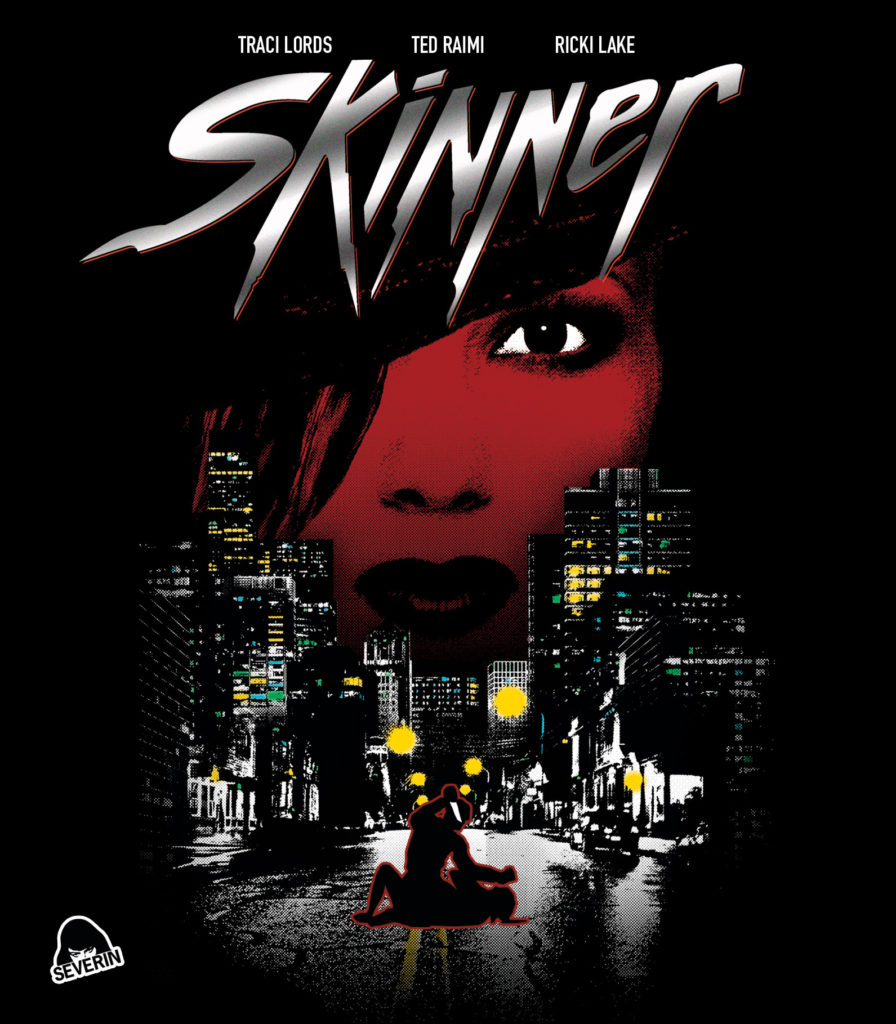

Not that you’re going to gather the family around the television for a wholesome time or anything, but it’s almost immediately difficult to take SKINNER seriously. Sure, it opens with an ominous — if not downright ponderous — opening credits sequence, with a droning, menacing Casio synthesizer riff. But for some reason, it’s also intercut with shots of Traci Lords, ankle deep in a river, muttering to herself about some unseen person she believes will be joining her soon. They won’t be able to help themselves, she insists, as she broods through an obvious wig and a fedora. The disconnect between the weighty intent and the bewildering execution inspires chuckles that will eventually boil over into fits of laughter.

Left with more questions than, well, anything, the audience then meets Dennis Skinner (Ted Raimi), a boyish, affable twentysomething looking for a place to shack up. A classified ad leads him to Kerry Tate (Ricki Lake, bringing the number of CRY-BABY alums up to two), a struggling, working class woman renting out an extra room out of necessity: while her asshole husband (David Warshofsky) has some (strongly worded, borderline abusive) reservations about a stranger moving in, she argues that they could use the money. Unbeknownst to either of them, Skinner moonlights as a complete psychopath who stalks the local red light district for prostitutes he can skin alive. Whatever inclination you might have had about taking SKINNER seriously dissipates once you realize the title’s double entendre.

But it’s not exactly a riot, either, at least for the first half or so, when the film plods between Skinner’s exploits, the Tates’ marital strife, and Traci Lords mumbling in a seedy motel room. The script (slowly) reveals that Lords is Heidi, a former prostitute and one of Skinner’s would-be victims. One of the lucky few to escape his deranged grasp, she’s dedicated herself to tracking the maniac and ending his reign of skid row terror. She’s truly fascinating, possibly even more so than the title character himself, if only because her turn feels genuinely strung out: it’s difficult to tell if it owes to her amateur background as an actress or if she’s just that convincing as a shattered, burned out junkie.

Unfortunately, the film does her few favors, rendering her almost comically inert as she mutters repetitive monologues to herself, almost as if she were trapped in some brain-damaged film noir. At a certain point — maybe after the third instance — it becomes weirdly entrancing: Lords’s acting is unconventional, and maybe even a bit paradoxical. Somehow, it’s unconvincing and completely earnest all at once, dialed into that strange plane where a character becomes compelling by the sheer force of the film’s bizarre will.

Foiling her is Raimi, whose presence is much more wry and warped. That natural Raimi brothers impishness guides his performance, constantly threatening to unravel Dennis’s façade: there are times when it’s obvious he’s just barely holding together the act that he puts on around Kerry and his co-workers. His twisted, scummy deeds create an obvious dissonance because, you know, it’s Ted Raimi going nuts and skinning women alive. Director Ivan Nagy feels keenly aware of the disconnect and deftly builds towards it by revealing only quick glimpses of Skinner’s murders before finally turning Raimi loose.

In a positively gonzo sequence, Skinner regales a flayed corpse with his very own perverse origin story. As he peels off some ultra-convincing chunks of viscera (a shout out is in order for KNB’s expectedly gruesome effects), he takes a demented stroll down memory lane, recounting how his coroner father did the post-mortem on his own wife, much to the horror — and fascination — of young Dennis. It’s the stuff out of Serial Killer 101, but Raimi injects it with a manic energy: he’s all cackles and wild gesticulations as he dons the woman’s face as a new skin, cementing SKINNER’s status as a work of flailing, lunatic provocation. Forget any brooding, thoughtful exploration about a madman’s psyche or the nature of evil: this thing mostly exists to let Ted Raimi go buck wild at the expense of the women, men, and even animals that cross his path.

In doing so, it gets really caught up in the fervor of worshipping at the grindhouse altar. Like an edgy comedian looking to push the boundaries of taste and humor, it loses its damn mind and starts to poke and prod its audience with disreputable outbursts. An ill-fated dog falls prey when Skinner feeds it the rotting flesh of a previous victim, a turn that inspires some sideways glances and nervous fidgeting. Even more unsettling is an episode involving Dennis’s African-American co-worker, whose playful needling and shit-talking on the job puts him in the maniac’s crosshairs. Not content to simply to rip this man’s skin from his body, Dennis stitches it into a full body husk and takes to the streets, imitating the dead man’s mannerisms as if he were part of an especially unhinged minstrel show. Even those nervous fits of laughter abruptly halt, sort of like when someone tells a racist joke and the room goes silent and things just become uncomfortable.

Clearly, SKINNER is complete and utter nonsense, and yet this particular stretch still feels like a false, troubling note. Not to relitigate 25-year-old art, but we are more attuned to how wrong-headed this stuff is now, even more so than folks were in 1993, so SKINNER feels like a relic from the more reckless, no-fucks-given exploitation era. You have a hard time imagining it ever being made today, where it’d (fairly) be deemed Highly Problematic. It’s also fair to point out that Dennis is a psychotic murderer whose racism only makes him even more despicable. Staging a maniac in blackface does not equal an endorsement, you might say, but it’s also fair to note how the film wants to sweep you up in its madness. Without the cold detachment of HENRY, SKINNER feels weirdly entertaining before it bludgeons you with its racist and misogynistic streak. If Nagy’s aim was to make audiences uncomfortable after all, then mission accomplished.

Admittedly, that goal doesn’t exactly linger, as Nagy tries to sweep it under the rug to build up to a silly climax. The real magic happens the couple of times Lords and Raimi share the screen, at which point SKINNER becomes a Looney Tunes routine, complete with over-the-top violence and absurd dialogue. A last-stab effort a social commentary during their final exchange attempts to find some meaning in the madness, but, like Lords’s ridiculous wig, it’s not fooling anyone: SKINNER revels in bouncing these two disparate performers off of each other. For most of the film, they might as well be operating in different galaxies: Lords is uber-serious in her giallo-chic getup, laboring to deliver each pained, confessional bit of dialogue. Raimi’s cutting it up — both literally and figuratively — just waiting to carve every bit of the scenery and stuff it into his mouth. When the twain finally meet (with poor Ricki Lake caught in the middle), it’s a flurry of savagery, garish make-up reveals, and a total disregard for good taste.

Is it enough to salvage SKINNER? I don’t know — oddly enough, it personally brings me back to square one. Like HENRY, it’s tough to watch, but for different reasons: where that film unnerves because it’s hauntingly convincing, this one is just clumsy and puerile in its attempt to get a rise out of the audience. The word “inelegant” comes to mind: this isn’t the calculated rawness of McNaughton’s film, but rather a gangly, weird, tasteless, and discordant cacophony of serial killer clichés and outlandish gore. And while plenty of other movies might offer that, SKINNER is the only one that also generously offers Ted Raimi, Traci Lords, and Ricki Lake too. Give it credit for cornering that very specific niche.

The disc:

Given that SKINNER went straight to video in the U.S., it’s disconcerting that its various releases have been lackluster. Undercut by censored versions and murky VHS transfers, it’s never really had much of a chance to shine until Severin’s recent Blu-ray release. First things first: this is the complete, unedited version that leaves the infamous mid-movie skinning sequence left intact. Secondly, the transfer is unbelievable. Struck from a new 4K restoration, the film — as grungy and low-budget as it is — looks immaculate, so much so that you can see some light (but welcome) wear-and-tear on the negative. It’s an impressive result of a years-long labor of love, and it shows.

One of the centerpiece supplements, an interview with Nagy himself, reveals this project stretches back to 2007, when the search for the film’s original elements began. The interview, which was also conducted over a decade ago, is quite informative, even if SKINNER itself begins to feel like a footnote as the now deceased filmmaker recounts his family’s migration from Hungary and his rise in the filmmaking ranks. He also defends himself from the accusations that arose in the wake of the Heidi Fleiss scandal, taking the time to especially discredit Nick Broomfield’s documentary on the subject. As Fleiss’s boyfriend at the time, he naturally landed in the tabloids and before paparazzi cameras, and he was clearly affected by it (in fact, this knowledge in conjunction with Lords’s junkie prostitute being named “Heidi” makes SKINNER feel like a weirdly confessional film). Don’t mistake that for contrition, though — he’s unapologetic to the end, especially about SKINNER itself, a film that feels even more confrontational after this interview.

Raimi appears in “Under His Skin” and, like Nagy, recounts his career before tackling SKINNER specifically. He touches on and brings context to some of the aforementioned controversial scenes, which shows a nice bit of awareness on his part. “Bargain Bin VHS” gives screenwriter Paul Hart-Wilden a chance to explain his inspiration and intent with the film, particularly how his fascination with serial killers shaped the script. Finally, editor Jeremy Kasten dishes a little bit of dirt in “Cutting Skinner,” wherein he discusses the mad dash to complete the film. A 12-minute outtake and extended take reel provides a more in-depth glimpse at one of the show-stopping gore sequences, while a trailer rounds out an impressive disc.

If you managed to snag this one during Severin’s Black Friday sale, you’ve not only managed to have an early crack at it, but you also scored a limited edition slipcover. If you didn’t, fret not: Severin is releasing a standard edition (sans slipcover) with the same supplements. Either way, it’s likely to be the only release on your shelf that proudly boasts its “complete hooker-flaying sequence.”

Tags: Blu-ray, David Warshofsky, Horror, Ivan Nagy, Jeremy Kasten, Paul Hart-Wilden, Richard Schiff, Ricki Lake, Severin Films, Ted Raimi, Traci Lords

No Comments