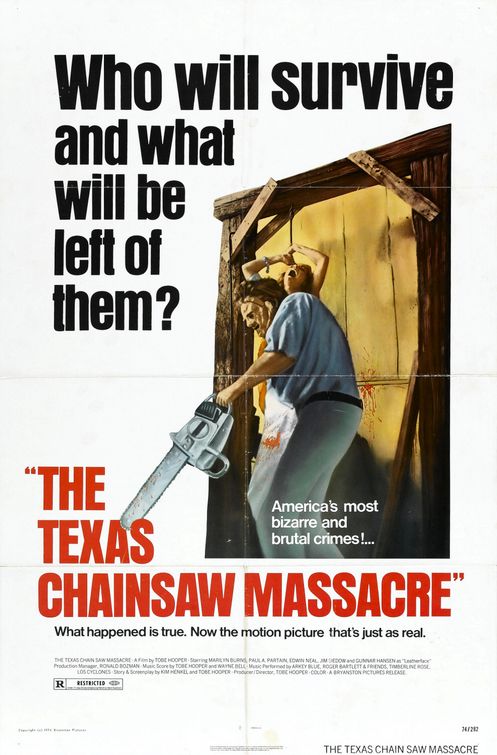

THE TEXAS CHAINSAW MASSACRE was a movie of its time, and it reflected that as surely as any other more prestigious and acclaimed American classic. It’s a genuinely important American film. Movies of the era such as THE GODFATHER, TAXI DRIVER, ONE FLEW OVER THE CUCKOO’S NEST, and A CLOCKWORK ORANGE are justly heralded, but THE TEXAS CHAINSAW MASSACRE is equally important as a historical document of the 1970s.

The movie arrived in 1974. This was the era of the Vietnam War. The war was still going on when the movie was being made. What director Tobe Hooper and his collaborators did, consciously or otherwise, was to capture the anger of the era. Obviously there are no politics directly addressed by the story, which is at its core, like PSYCHO before it and THE SILENCE OF THE LAMBS after it, a hyper-fictionalized elaboration of the Ed Gein story. The political furor of the era is not to be found in the main text, but instead, it roils underneath, embedded within the ferocious, hopeless atmosphere of the piece.

Five years before THE DEER HUNTER or APOCALYPSE NOW, THE TEXAS CHAINSAW MASSACRE managed to reflect the cultural unease, disillusionment, and nihilism that the war in Vietnam, by all accounts, engendered in American minds. Note how iconic franchise villain Leatherface carries a chainsaw as his weapon of choice. The chainsaw treats human bodies like inanimate objects – like meat. The chainsaw is more businesslike, less up-close-and-personal than say, the fangs of Count Dracula, or even the knife wielded by Michael Myers. The house where Leatherface dispatches most of his victims is, literally, a slaughterhouse. Meat lockers line the walls. Bones decorate the room like promises. The ruddy cinematography by Daniel Pearl gives the images alarming texture. You can almost smell the coppery metallic death in the air.

Horror audiences have become inured to this kind of imagery but in 1974, it had significance. Human bodies treated like cattle, hung by meat hooks and clubbed in the head with ruthless efficiency. It’s an impersonal, industrial kind of murder. When the movie does demand an emotional response to the murders, it does so in unusual, script-flipping sorts of ways.

Think of Franklin (Paul Partain), the wheelchair-bound character – sure he’s disabled but he’s also one of the most intolerable creatures in film history. This is a type which movies normally sentimentalize, yet Franklin is so shrill and abhorrent that, if anyone, most audiences end up siding with Leatherface by the time Franklin is sent to his fate. As the film progresses, the murders are purged of sentiment. Only madness awaits. Chaos becomes constancy.

In THE TEXAS CHAIN SAW MASSACRE, human beings are just meat, ground up by an unintelligible enemy that cannot be reasoned with or dissuaded. Now think again of the Vietnam War. In general terms, the first sentence of this paragraph could be describing the actions of a murderous giant carrying a chainsaw, or that of a lengthy and unpopular overseas conflict which tore apart many American lives. How much of this thematic resonance was intentional on the part of the young filmmakers and how much was intuitive does not matter as much as the fact that it IS resonant.

What an opportunity, then, for a horror movie released in 2013, to address some comparable sociopolitical subtext. Again America is embroiled in an unpopular war overseas. Unlike the era of the Vietnam War, however, many Americans are not concerned with the details of our current war on a daily basis. Modern war affects some of us profoundly and many of us hardly at all. This is very fertile ground for the kind of veiled commentary and brutal satire which is buried within so many of the great horror films.

So far, the current practitioners of the genre are largely failing us. This year’s TEXAS CHAINSAW, which I reviewed back in January and from which I expanded this piece, was an absolute failure to engage either the individual intellect or the sociopolitical viscera. The most popular horror films of 2013 so far have been haunted-house films like THE CONJURING, spooky and relatively innocuous as far as cultural resonance goes. Zombies remain the predominant horror paradigm of the moment, whether they be sweet and lovelorn as those in WARM BODIES or swarm-y and CGI-abetted as in WORLD WAR Z or impeccably-designed and personality-free as in The Walking Dead. And if it’s not zombies, it’s vampires. And so it has been for over ten years now.

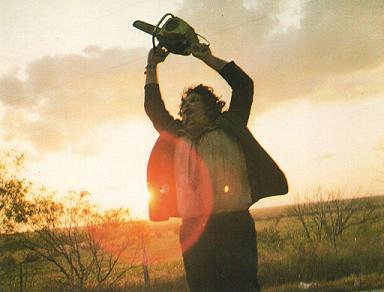

Ghosts. Zombies. Vampires. Dead things. This is what our horror films are reflecting back upon us. What does that say about our modern preoccupations? Things have changed. Times have changed. Of course, OF COURSE, horror films are almost always about death in one form or another. But 2013’s horror movies by and large feel antiseptic and by nature of their generous CGI budgets, ultimately safe. THE TEXAS CHAIN SAW MASSACRE, by contrast, feels like a documentary from Hell. THE TEXAS CHAIN SAW MASSACRE, even looked at today, has an energy, an urgency, a vitality, a ferocious vigor to its bloodletting which stands in contrast to the majority of today’s horror output. Look again at that final, indelible image: Leatherface, denied his final victim, swinging his chainsaw with simultaneous fury and futility in a blind rage, lit by a dawning sun. For a killer of masses, in that ultimate moment he is alive. It’s his Marilyn Monroe moment. This is how a monster becomes a star.

THE TEXAS CHAINSAW MASSACRE is the midnight movie this weekend at New York City’s IFC Center.

@jonnyabomb

- [THE BIG QUESTION] WHAT’S YOUR FAVORITE FEMALE ENSEMBLE IN MOVIES? - July 22, 2016

- [IN THEATERS NOW] THE BOY (2016) - January 24, 2016

- Cult Movie Mania Releases Lucio Fulci Limited Edition VHS Sets - January 5, 2016

Tags: Chainsaws, gore, Gunnar Hansen, Horror, John Larroquette, Leatherface, politics, The 1970s, Tobe Hooper, violence

No Comments