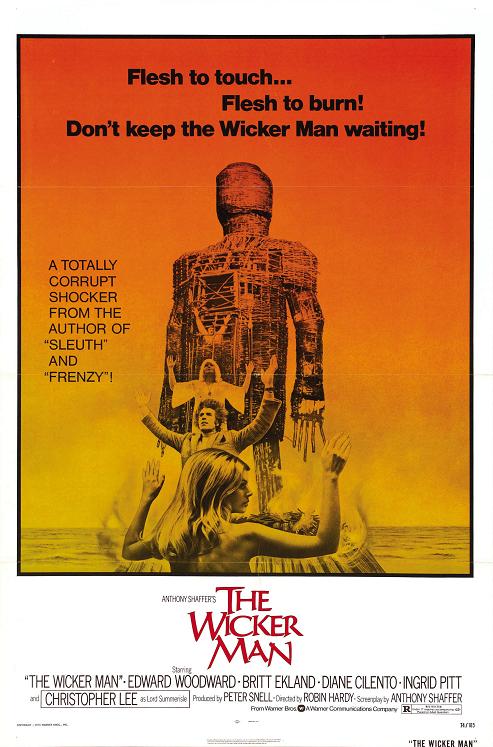

THE WICKER MAN is one of the most notorious British cult films of all time. One could argue that the greatest overall gift ever given to horror cinema by the United Kingdom was the Hammer films catalogue, and Great Britain has an estimable tradition of lesser-known horror pictures such as LET SLEEPING CORPSES LIE and DEATH LINE [ironically; those two were directed by a Spaniard and an American, respectively — read more on the latter here]. However, out of all the great horror movies made and set in the UK, THE WICKER MAN is possibly more famous than any one title from that esteemed backlist. Its notoriety is well earned. It’s a shocker, a quite literal slow burn. I’d be only half-kidding if I told you that, just as JAWS made me leery of skinny-dipping in the Hamptons, THE WICKER MAN is the main reason you’ll never see me at the Burning Man Festival. It ain’t the same thing, but all the same, no good can come out of giving that many hippies the gift of fire.

To me, THE WICKER MAN has always felt like an anomaly in the horror genre. For one thing, it has highbrow origins. The script was written by Anthony Shaffer, who wrote FRENZY for Alfred Hitchcock and who adapted his own stage play SLEUTH for the film of the same name, directed by Joseph L. Mankiewicz (ALL ABOUT EVE) and starring Laurence Olivier and Michael Caine. THE WICKER MAN was his next film after those two were released. Robin Hardy directed. The star was Edward Woodward, a decorated stage actor. This was his first leading role in films.

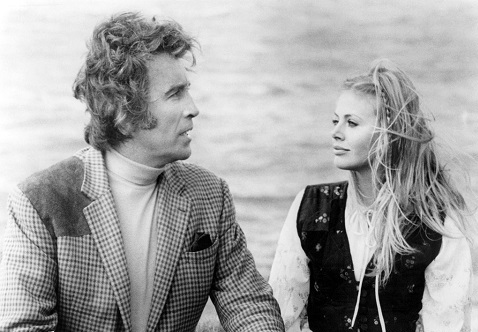

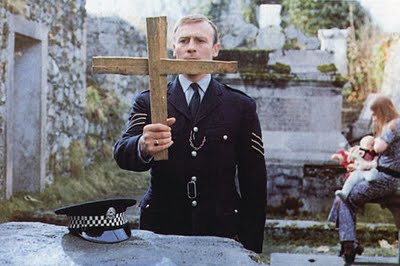

Woodward plays the upright, upright police Sergeant Howie, who heads to a remote island called Summerisle to investigate the presumed disappearance of a girl named Rowan Morrison. Howie has to stay on Summerisle for the duration of his investigation, and he very quickly is put off by the ways of the locals. The populace is openly hypersexual, from soon-to-be Bond girl Britt Ekland all the way down to a bunch of people you may be less interested in seeing naked. Howie is so serious about his Christian faith that he’s resolutely celibate, which means that he’s not only flabbergasted by the orgiastic ways of the villagers, but horrified by the proudly pagan rituals he witnesses.

These rituals are more creepy than downright scary, or at least that’s how I personally felt, after hearing this film’s reputation. I thought it was going to be more scary, really. I purchased that DVD copy of the film with the quote “the CITIZEN KANE of horror movies” on the cover, and that kind of press is setting up expectations for a different sort of film. THE WICKER MAN is not consistently terrifying the way CITIZEN KANE is consistently excellent. It’s not consistently terrifying the way HALLOWEEN is nearly relentlessly terrifying. Its approach to horror is different than that. The prevailing tone for the majority of the film is eerie at worst. It saves its most frightful moments for last. There are moments of chilling suspense, such as when the villagers engage in the “Ritual Of The Sword” pictured below (Youtube clip here). It’s a kind of trial by fire in which costumed pagans hold swords in a star-like pattern through which brave souls are prompted to stick their heads, with the obvious danger of having their cabezas lopped off like dandelions.

Again, this is more sporadic suspense than sustained horror. That’ll come. The film has a determined pace, leading to a very heightened climax. But the search for Rowan doesn’t feel all that frenzied, to me anyway. The bulk of the story is mostly concerned with the clash between Howie’s faith and the foreign-to-him flower-child culture of the island. There are some obvious cultural overtones at play, considering the post-1960s era in which the film was released. But there are even more timeless issues going on here. The questions this film poses are less contemporary and more universal, ultimately more internal than external.

For much of its running time, THE WICKER MAN doesn’t feel much like a traditional horror movie . The folk-style score by Paul Giovanni is far from the scariest soundtrack in all of horror films, much of the events portrayed take place in broad daylight, and most of the villagers are unimposing, even friendly, for quite some time. One of the few signposts the audience gets is in the casting of the island’s alpha male and spiritual ringleader, Lord Summerisle. He’s played by Christopher Lee, one of the greatest and most iconic ghouls in horror history. Lee has always been an immensely talented and sophisticated artist, but the power of his image in so many Hammer films limited his castability. Here he’s playing a strikingly different character. His hair grown out, his complexion more flushed, he doesn’t look much like a vampire. He looks downright handsome. This is Dracula replenished, a monster on vacation. (If you want to see more pin-up idol Christopher Lee, check out HANNIE CAULDER. Raquel Welch’ll bring it out of you.) Lord Summerisle is an eminently charismatic figure — in the grand reckoning, chillingly so. But even still, at this point in film history, after nearly twenty years of Hammer horror, the presence of Christopher Lee is an ill omen for the story’s hero.

***SPOILERS AHEAD***

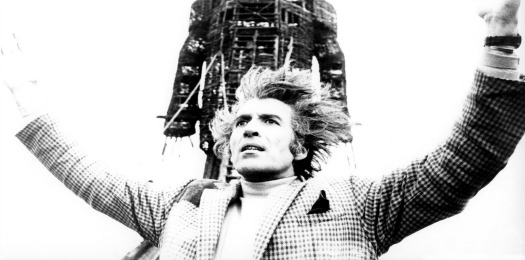

In the end, Sgt. Howie finds out that Rowan Morrison was never lost. She is at home with the denizens of Summerisle, an agent sent to bait a trap. Howie is stripped and bound and lumped in amongst livestock to serve as a human sacrifice. In American movies your best chance of survival is your virginity; apparently that rule doesn’t fly overseas. Howie’s celibacy makes him the perfect candidate for burning in the eyes of the Summerisle pagans. They believe they need to make a sacrifice to bring their harvest, so that’s what they do. In the end, the sergeant is powerless.

What makes THE WICKER MAN so haunting is this essential issue of faith. Is the film a critique of paganism, a bolstering of traditional Christianity? Is Howie meant to be a Christ figure — considering how being burned inside a wooden effigy isn’t too far removed from the horror of crucifixion? Or is there something far darker being suggested?

Looked at objectively and practically, Howie’s faith doesn’t save him. His prayers go unanswered. He seems to realize they won’t. Either way, he most definitely dies. That isn’t to say that paganism is right and Christianity is wrong, or even the reverse, but it may be intended to mean that none of it matters. Spiritually speaking, it’s true that Howie was a pious man, so we’re free to imagine that he made it to heaven after the credits rolled. But that isn’t what’s onscreen. Onscreen, we see only ash.

As far as movies go, this isn’t a happy ending. Without going into my personal belief system, I will at least state that I find this potential rebuke to faith and spirituality both unbelievably harsh and upsetting. For the film to be effective, which it is, it almost doesn’t matter what you bring to the film as an audience member in terms of religious belief — having spent so much time with Howie, and knowing so well where he stands as a character, it’s disturbing to see his individual sanctuary torn down so cruelly. To me, that makes this a cousin film to THE EXORCIST (released in America the same year — synchronicity maybe), the true horror of which, to me, has more to do with the central theme of religious faith lost and found, and less to do with the vomiting and the head-spinnings. It’s the rare film that is scarier for what it implies than for what is seen, but THE WICKER MAN, to me, is one of those soul-punchers.

THE WICKER MAN is playing through Thursday, with a 40th-anniversary restored and extended cut, at New York City’s IFC Center.

— JON ABRAMS.

- [THE BIG QUESTION] WHAT’S YOUR FAVORITE FEMALE ENSEMBLE IN MOVIES? - July 22, 2016

- [IN THEATERS NOW] THE BOY (2016) - January 24, 2016

- Cult Movie Mania Releases Lucio Fulci Limited Edition VHS Sets - January 5, 2016

No Comments