There’s something dangerous and unsettling about the comedic persona of Danny McBride. Ever since breaking through with his star-making indie THE FOOT FIST WAY, McBride has become part of the roving Judd Apatow, the weed-and-improv soaked crew of modern bro-doofus miscreants ad-libbing their way through a series of shaggy-dog comedies that have the vibe of smarter, more humane, less antagonistic Happy Madison films. McBride fell into the same crew that contained Seth Rogen and Jonah Hill, James Franco and Paul Rudd, Craig Robinson and Michael Cera. McBride adopted their same jolly-stoner-dope bonhomie, cheerful boy-men stumbling into adulthood. In their films, if not always real life, they were good-natured but childish oafs, learning lessons in what it meant to be… if not mature, than at least looking towards maturity.

Except there’s always been something… off, about McBride’s embrace of this comedic persona — something menacing, something threatening. If Rogen was the dopey-stoner leader, Franco the blitzed oddball art-freak and Hill the neurotic, apoplectic sarcasm-dispenser, than McBride was the demonically smiling boor who hid a latent aggression behind his manchild exterior. The films he was in rarely tapped into this aspect of his persona — THIS IS THE END came closest, but in a chidingly satirical, kidding way — but ARIZONA strips away all the niceties. It exposes the volatile horror in McBride’s on-screen persona.

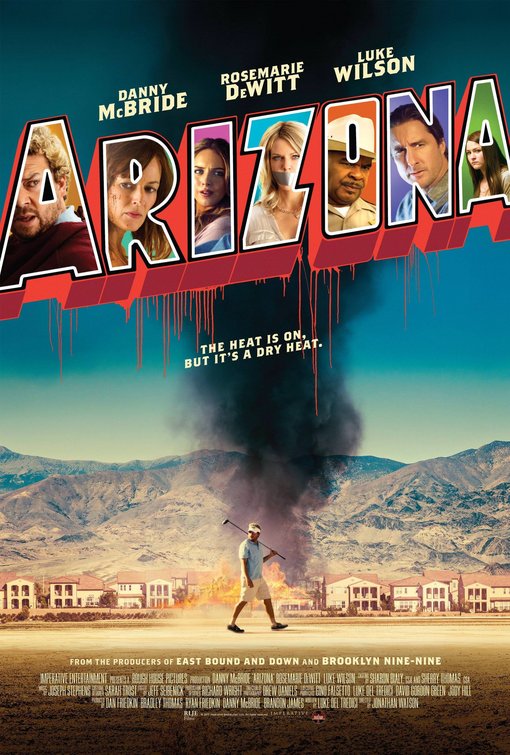

In ARIZONA, Jonathan Watson’s arrestingly creepy nutjob thriller, McBride isn’t stretching his acting muscles. He’s simply playing another variant on the “McBride type” — only this time he’s stripped it of all varnish, burrowing into the brutalist honesty of his comedic persona. He plays Sonny, who’s barely holding on in hs Arizona housing development during the 2009 housing crisis. Sonny has lost his wife, and he can barely afford to keep up the payments on the subprime loan that allowed him to buy a deluxe home in a desolate, failing prefab community baked into the sun-scorched American desert sands, despite a hare-brained entrepreneurship scheme selling frozen wine cubes, eager to show off, polite and apologetic yet also incensed when things veer out of his control. He’s also a rage maniac who is addicted to the thrill of murder; he’s as apt to kill you as give you a bag of ice for the bruise he just gave you. He’s the suburban middle aged bro as the murderous-middle-class-narcissist-next-door.

In other words, in ARIZONA, McBride is just playing a version of a typical McBride character — only now he’s also doubling as an ironically affable man-cave dwelling Jason Voorhees. He starts off by killing the smug misogynist realtor who sold him a bum deal, and then kidnaps the lone witness — Cassie (Rosemarie DeWitt), a fellow realtor who Sonny sees as a kindred spirit: a separated mother, forced to sell off bogus subprime loans in order to escape the looming shadow of the one foisted upon her. Sonny, broken and lost, keeps her around on his odyssey of violent revenge against an uncaring world.

There’s not much to ARIZONA other than the gleeful dark subversion of McBride’s comedic persona. And maybe that’s all it needs. With screenwriter Luke Del Tredici (Brooklyn Nine-Nine), Watson has crafted a tidy little B-thriller; at its heart, it’s just the story of a troubled, strong-willed woman facing up against a slathering man-monster maniac. It’s a story we’ve all seen before, and on that note, Watson’s film isn’t an act of breakthrough grandstanding. It’s a modest little thriller, and Watson doesn’t do enough with the housing bubble background. I wish the director had used the thematic backing of the housing crisis as more than a MacGuffin driving Sonny’s death trip. Sonny and Cassie are both victims of predatory lending practices, yet there’s no sense that Sonny’s rage is spurred by the way he’s been screwed over by a cheerfully unempathetic capitalistic culture. As written, Sonny comes off like he’s always been a pressure cooker, a barely-concealed pit of aggression ready to snap. You always feel like he was a murderer to be, regardless of what lights that wick; he’s less a sympathetic anti-hero than a snarling wolfman.

Then again, that’s the perverse appeal of the McBride cinematic persona, and the movie is aware of that. The supporting cast is stocked full of familiar comic actors — Kaitlin Olson, Luke Wilson, David Alan Grier — but none of them are really given anything to do; they simply exist as targets for Sonny’s seething fury. The only actor who is given a role close to being on par with McBride’s is DeWitt, playing the yin to his crackling yang. If McBride represents the anger of the real estate crash, then DeWitt is the desperate worry of it, dodging calls from debt collectors and borrowing money from her wealthy ex. The movie could have done more to exploit that dichotomy — the two faces of financial crisis. Instead ARIZONA boils down to a cat and mouse game between (masculine) psychopath and (feminine) victim.

That said, even as Watson, in ARIZONA, fails to fully embrace the thematic underpinnings of his film, he still creates a strong and effective pulp thriller. It’s not necessarily a memorable film, but a compulsively watchable one, and one that gets a truth we’ve long been denying: Danny McBride, for all his gruffly insinuating chumminess, is really one scary beast.

Tags: Arizona, Danny McBride, David Alan Grier, David Gordon Green, Elizabeth Gillies, Jody Hill, Jonathan Watson, Kaitlin Olson, Luke Del Tredici, Luke Wilson, Rosemarie DeWitt, Seth Rogen

No Comments