There are few actors who seem less suited to a genre than Tom Hanks is to horror. The development of Hanks’s career – from plucky leading man of ‘80s comedies to the Academy darling of the ‘90s – seems almost artificially designed to appeal to Generation X, the children born in the sixties through the early-eighties who have never known a Hollywood that did not include a variation of Tom Hanks. In many ways, Hanks has become a form of cinematic historian, guiding a new generation through the events surrounding World War II or the development of America’s space program. If countries could be played by individual actors, many people would choose Tom Hanks to play America without a moment’s thought.

And yet, early in his career, Tom Hanks achieved several key milestones as an actor by appearing in horror films, an achievement all the more noteworthy since he has no interest whatsoever in the genre. These films, while varying in their (general lack of) quality, all point to important landmarks in Hanks’s career. Let’s take a moment and appreciate the awkward marriage that is Tom Hanks in horror by looking at his four projects that fit the bill: 1980’s HE KNOWS YOU’RE ALONE, 1982’s MAZES AND MONSTERS, 1989’s THE ‘BURBS, and 1992’s episode of TALES FROM THE CRYPT.

HE KNOWS YOU’RE ALONE (1980)

… a.k.a. Tom Hanks’s First Film or Television Credit

In 1980, Tom Hanks made his big screen debut in the teenager slasher, HE KNOWS YOU’RE ALONE. The film follows a young woman, Amy (Caitlin O’Heaney) in the week leading up to her wedding. Her fiancée heads off to the wilderness to have a bachelor party with his friends, while Amy plans her bachelorette party and tries to avoid bumping into Marvin (Don Scardino), her ex-boyfriend and ongoing crush. Meanwhile, a man with a thing for killing brides stalks her wedding party while a police officer stalks the man stalking her wedding party. In the end, a lot of bridesmaids die.

+001.jpg)

Contemporary reviews of HE KNOWS YOU’RE ALONE weren’t mixed; they all hated the film. Michael Blowen of the Boston Globe referred to the movie as having production values “only slightly better than those in my uncle’s home movies,” while Tom Buckley of the New York Times refers to Scott Parker’s screenplay as being “as full of holes as the victims.” Each review firmly places it within the context of American horror cinema, noting that it was part of a wave of pale HALLOWEEN and FRIDAY THE 13th imitators who were meant to (cheaply) capture the zeitgeist of ‘70s horror films. Today, HE KNOWS YOU’RE ALONE exists more as the answer to a trivia question – “What was Tom Hanks’s first film credit?” – than as an important part of horror canon.

You don’t want to make too many broad statements about an actor’s first film – after all, Hanks’s motivation likely had more to do with the reported $785 weekly rate and SAG card he received for the credit – but there are a few things about his performance that give hints to his later roles. Like many of Hanks’s protagonists, Elliot observes the actions around him at something of a distance, possessing great charm but also an awareness of what is at stake. When Elliott asks Amy’s friend Nancy (Elizabeth Kemp) on a date, he goes with them to a local county fair and waxes poetic on the very nature of the horror film.

“Most people do, actually. I mean, like to be scared. It’s something primal, something basic. Horror movies and the roller coasters and the house of horror ride. And you can face death without any real fear of dying. It’s safe. You can leave the movie or get off the ride with a vicarious thrill and the feeling that you just conquered death. One hell of a first-class ride.”

However, perhaps the most Tom Hanks-esque moment for Elliot is that he was so liked by the filmmakers that they re-wrote his ending. According to an Entertainment Weekly article by Chris Willman, “After making his brief film debut as a victim’s boyfriend, Tom Hanks inexplicably disappears; his death scene was scripted, but, the filmmakers reveal, they ‘liked him too much…to kill him.’” With one less dead teenager to pad the body count, HE KNOWS YOU’RE ALONE decides to have Nancy pull double-duty to make up for it. Whereas most of the film is surprisingly chaste in its depictions of sex and violence, Kemp is given a topless shower scene as a throwback to a bit of dialogue from Elliot on PSYCHO; she is then decapitated – the only bodily mutilation that exists in the film – and her head thrown in the fish tank. Nancy suffers so that Elliot can live and everyone still goes home satiated.

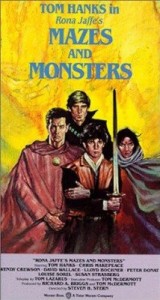

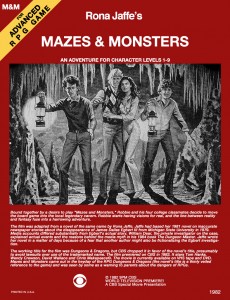

MAZES AND MONSTERS (1982)

… a.k.a. Tom Hanks’s First Leading Role in a Film, Made-for-Television or Otherwise

In 1979, college student James Dallas Egbert III disappeared from his dorm room at Michigan State University into the tunnels underneath campus. Egbert suffered from depression and struggled underneath the influence of his parents; however, a private investigation of Egbert’s life would find tenuous links between Egbert’s disappearance and popular Dungeons & Dragons sessions held at the university, and it was not long before the media decided that Egbert had died in a game of D&D gone wrong.

This was not true, of course. Egbert would be discovered months later, only to succeed in his suicide attempts shortly thereafter. However, the link between adolescent violence and Dungeons & Dragons was cemented in the public’s mind, and several books intended to capitalize on these fears would show up in the years to follow. The most popular of these books was Rona Joffe’s Mazes and Monsters, a tale of four rich white college students who are so fanatical about the game “Mazes and Monsters” that they begin to play a live version of it in an underground cave system near the campus.

As Grady Hendrix’s article notes, there was not a lot of truth to Joffe’s depiction of the appeal and interaction involved in a roleplaying game, but Joffe’s book was catchy enough to bring a television adaptation in 1982. In it, Tom Hanks plays Robbie, the member of the group who becomes untethered from reality and wanders the streets of New York on a holy quest to find his missing brother. The persona that is attached to Hanks – albeit retroactively – means we find Robbie sympathetic even when spouting off nonsense to homeless people in the subway of New York or explaining to his friends that he should jump off the World Trade Center because, “I have spells. I’m going to fly.” However, the film plays as a reshuffling of the REEFER MADNESS paranoia, where a generational divide leads to the condemnation of a recreational activity.

As with most low-budget morality plays, MAZES AND MONSTERS won’t let us go anywhere until the filmmakers are sure that we have Gotten the Point. At the halfway mark of the film, the camera slowly zooms in on the face of a character as she solemnly declares, “The most frightening monsters are the ones who exist in our minds.” As true as this may be, nobody in the movie has any interest in treating the underlying cause of Robbie’s illness. MAZES AND MONSTERS takes every opportunity to warn people of exposing fragile minds to games like Dungeons & Dragons while offering only passing glimpses of Robbie’s home life. The first time we see his parents, his mother is being loudly admonished by her emotionally-distant husband for being drunk; the second time, his mother is holding a full glass of wine and ignoring the warning sign of Robbie’s friend calling to say he is missing; and the third time, she is holding a vase of flowers and clucking after her son. Does Robbie have an undiagnosed mental illness that a more attentive parent could have treated? Does the blame fall on either his missing father or alcoholic mother for abandoning Robbie after the loss of his sibling? MAZES AND MONSTERS says no, and even gives Robbie’s mother a tearful scene where she tells Robbie’s friends that she does not blame them for what happened.

THE ‘BURBS (1989)

… a.k.a. Tom Hanks’s “Last” Comedy

This year marks the 25th anniversary of THE ‘BURBS, the horror-comedy directed by Joe Dante and starring a still-young Tom Hanks and still-old Bruce Dern. Being that 25 is a notable anniversary, many sites have taken the time to run retrospectives on the film. Read 6 Scenes We Loved From THE ‘BURBS at by Christopher Campbell at Film School Rejects, or perhaps the Mike Ryan piece at the Huffington Post that argues that THE ‘BURBS really is Tom Hanks’s “crossroads movie.” I do not have much to say beyond what Campbell and Ryan have already written, save one note. Like the other films on this list, Hanks seems to use the horror genre to get something he wants – namely, a chance to play a more serious version of himself.

TALES FROM THE CRYPT; “None But the Lonely Heart” (1992)

… a.k.a. Tom Hanks’s First Time in the Director’s Chair

In 1992, Hanks made his directorial debut in an episode of TALES FROM THE CRYPT titled “None But the Lonely Heart.” In the episode, Treat Williams plays a confidence man who seduces rich widows he meets through a video dating service. Playing off their heightened sense of mortality, Williams marries them, convinces them to give him power of attorney so he can manage their finances, and then poisons them and pockets their millions. Hanks’s move behind the camera was part of a long-standing tradition of TALES FROM THE CRYPT to offer actors the opportunity to direct television. In Tales from the Crypt: The Official Archives, author Digby Diehl discusses the ways in which the show would accommodate actors looking step behind the screen.

“There have been endless variations of the time-worn joke in Hollywood that everyone wants to direct – on TALES FROM THE CRYPT, they can make it happen, and they can make it happen in an environment where it is safe to make mistakes, without endangering an eight-figure budget or a “bankable” reputation. […] The only thing TALES asked of its star-director was that they act in at least one scene in the segment, so that HBO could use their likenesses to promote the series. ‘We gave them an opportunity to do something they’d always wanted to do,’ says Joel Silver. ‘All they had to do was lend us their face.’”

In sitting behind the camera for the first time, Hanks would get paired with a regular cinematographer on the show – John Leonetti, who would go on to shoot the INSIDUOUS films with James Wan – and, as Diehl hints, try his hand at directing under relatively low stakes. Hanks manages a few nice compositions in the episode but does not stand out as a particularly flashy director; thankfully, the performances by Treat Williams, Frances Sternhagen, and Henry Gibson provide just the right balance of camp and gothic horror. In fulfilling his obligation to show his face, Hanks also has a brief turn as the dating service owner, demonstrating the proper way to sound a death rattle when being thrown headfirst into a television set and electrocuted to death. In the few places that Hanks has talked about his experience on TALES FROM THE CRYPT, he is quick to give credit to his actors, noting in an interview with Larry King that he was “saved by the performances and the professionalism of Frances Sternhagen and the (sic) Treat Williams.”

If Hanks learned anything from his time on TALES FROM THE CRYPT, it appears to be a select appearance by himself can help sell his role as a director. With the exception of the A LEAGUE OF THEIR OWN television series, Hanks has made a small appearance in every film or television episode that he has directed, even if it is only as a bit part. Hanks seems to enjoy his role as producer – helping guide the kind of projects he finds interesting through the development phase and into production – but his interests as a director seem to only extend as far as the types of projects he would act in anyways.

– MATTHEW MONAGLE (@LABSPLICE).

- [THE BIG QUESTION] WHAT’S YOUR FAVORITE FEMALE ENSEMBLE IN MOVIES? - July 22, 2016

- [IN THEATERS NOW] THE BOY (2016) - January 24, 2016

- Cult Movie Mania Releases Lucio Fulci Limited Edition VHS Sets - January 5, 2016

No Comments