There is a passage near the end of Hunter S. Thompson’s classic outlaw travelogue Hell’s Angels which reads “The streets of every city are thronged with men who would pay all the money they could get their hands on to be transformed – even for a day – into hairy, hard-fisted brutes who walk over cops, extort free drinks from terrified bartenders and thunder out of town on big motorcycles after raping the banker’s daughter. Even people who think the Angels should all be put to sleep find it easy to identify with them. They command a fascination, however reluctant, that borders on psychic masturbation.” Though written over 50 years ago, it’s a quote I am reminded of often amidst America’s ongoing wave of populist antihero entertainment

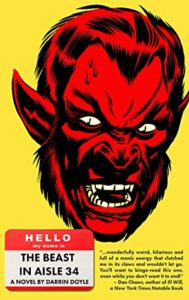

(a trend that started gaining steam in the early aughts with shows like The Sopranos, The Shield, and Breaking Bad, and has shown no sign of slowing down since). As modern masculinity has evolved steadily away from both brute manual labor and patriarchal “head of the household”-style power, the idea of violent criminality as escapist fantasy has experienced something of a boom in the entertainment world – a still-expanding narrative bubble that seeks to capitalize on the latent, collective male desire to break free of civil society with all its oppressive rules and red tape – to abandon even the pretense of morality in favor of becoming “the one who knocks.” Enter author Darrin Doyle, whose newest novel The Beast in Aisle 34, takes one look at that swollen bubble, and then gleefully bursts it with a swipe of its massive, hairy claws.

Sandy Kurtz is kind of a tool, in the most literal sense of the word. I mean, sure, the guy isn’t particularly likeable, but he’s also so innocuous that he doesn’t even quite rise to the level of being unlikeable. He’s just kind of there, a portrait of a man so deeply entrenched in routine – so utterly beaten down by the relentless mundanity of his life – that he functions as an actual tool; a cog in a really boring machine (one which he probably sells on the reg, as the Bathroom Fixtures Floor Manager at his local Lowe’s. Maybe a toilet fill valve, or a caulking gun. Something like that). His marriage to Pat, a wife who cheated on him in the not-too-distant past but is now pregnant with their first child, suggests a kind of dull-edged bear trap – a constant, grating reminder of both his past failures as a man, and his ever-shrinking options for any kind of a different future. His friends – fellow Lowe’s employees and hetero lifemates Ben and Jerry (they prefer Jerry and Ben) – are even sadder than him; middle-aged fantasy LARPers who seem to view even Sandy’s modest achievements as, at best, aspirational. What none of them knows about Sandy, however – and indeed, what Sandy himself is only just starting to get a handle on – is that an antihero lurks in all of us, somewhere beneath the skin, and that despite all the hair-raising crime spree adventures we enjoy via TV and movies, the IRL experience of throwing a wrench in your life’s own well-oiled machinery, however great it might feel in the moment, generally comes at the expense of whatever modest amount of control you had to begin with. And unlike Walter White, Sandy didn’t even make a conscious decision to “break bad.” He was just in the wrong place at the wrong time (ironically enough, taking a long walk after finding out about his wife’s affair) and got bit by a freakin’ werewolf.

The story that unfolds from there is a familiar one, but with a zanily gruesome bent, as Sandy struggles to balance his duties to Lowe’s, to his friends, and to his wife and unborn child, with his increasingly insatiable thirst for blood and carnage. Along the way he tangles with local vigilante Sasquatch hunters (or “Squatch Cops”), a sinister “Lycanthropy Support Group” that turns out to be anything but supportive, and ultimately actual law enforcement, in his quest to bring his own afflictive animal rage under control. But the farther he goes to protect his secret identity and newfound sense of power, the more he starts to enjoy it – even prefer it to the workaday schlubbery he left behind – and like all the amoral protagonists whose bad behavior we so love to watch, and judge, and gasp at (but also secretly root for, and maybe even get off on a little bit), in the end he is faced with the same stark choice: good or evil? Light or darkness? Man or beast? To paraphrase a well-worn sentiment, you either die an antihero, or live long enough to see yourself become the villain.

To say more of the plot would do this delightful book an injustice – I will readily admit that the ending surprised me, and I shan’t spoil it here – but I will happily carve out another paragraph in praise of Doyle’s crisp, easy style and the clever details he brings to Sandy’s predicament. The inclusion of cluelessly emasculated, performative male stereotypes like Bigfoot obsessives and fantasy role-players to bridge the metaphorical gap between the old Sandy and the new is a stroke of sly comedic genius worthy of Buffy the Vampire Slayer. Likewise, the time Sandy spends both in the wilderness and in captivity, learning practical survival skills by the skin of his teeth and improving his physical fitness for what may be the first time in his sedentary life, drives home the point that maybe if he’d just been a little more of a man to begin with, he might never have turned into the monster he is now. The fact that he works in a hardware store, but largely lacks even the basic tools to fix his life, kind of says it all. Sandy is inundated with masculinity signifiers every day of his life, but somehow remains relegated to helping suburban housewives and their henpecked husbands pick out the right faucets for their double vanity. He has the know-how. He just needs to grow a pair.

All of which is to say that, while Doyle may not have all the answers as to what Sandy woulda/coulda/shoulda done differently to avoid his antiheroic fate, he’s also not afraid to pose difficult, uncomfortable questions through his not-quite-unlikeable protagonist, and as I read, and judged, and gasped my way through Sandy’s darkly funny, grotesquely violent journey toward self-empowerment (alternate title idea: Eat Prey, Love), I found I didn’t necessarily have as many answers as I thought I did either. The Beast in Aisle 34 is by no means an apology for toxic masculinity, but it does have something fairly definitive to say about the repression of historically male hunter/provider/protector-type instincts, not by feminism, or homosexuality, or any of the other absurd, rightwing boogeymen the idiotic “men’s rights movement” tends to blame, so much as just by complacency; by drudgery; by the demands and compromises inherent to modern life. Independent, self-sufficient women still like a man who takes care of himself and knows how to change a tire. But more than that even, they like a man who likes himself; who feels secure enough in his manhood to not have to defend it, or hide it, or perform it all the time; who is comfortable enough in his own skin to keep the wolf inside at bay. Masculinity is not a static, all-or-nothing proposition after all, and it’s only when we decide it is that it becomes truly toxic, running around the woods ripping out throats and howling at the moon.

No Comments