One of my pet peeves in talking about films is the use of the word “dated” in a negative context. Even when it’s not used as a direct complaint or mocking statement (“Look at them using land lines! This movie is so dated!”), it’s often utilized as a semi-embarassed, apologetic excuse for a film (“It’s very good, even if the references in it are dated”) that someone otherwise likes.

In truth, the most compelling films are often the most interesting because of the aspects in them that can be considered “dated.” A film isn’t created in a vacuum – it’s created by people of a very specific time and place, and generally made for audiences of that era. he time-and-place-specific aspects of a film end up giving us a glimpse into not only the filmmakers’ intentions, but the complete atmosphere around them that caused the film’s tone, plot and themes to come into being. Sure, it’s easy to look at a movie from fifty years ago and dismiss aspects of it as being “of their time,” be the antiquity technological, thematic or political, but it’s a hell of a lot more interesting to take the timely nature of the film into consideration as part of its whole.

Case in point: 1970’s counterculture comedy BRAND X.

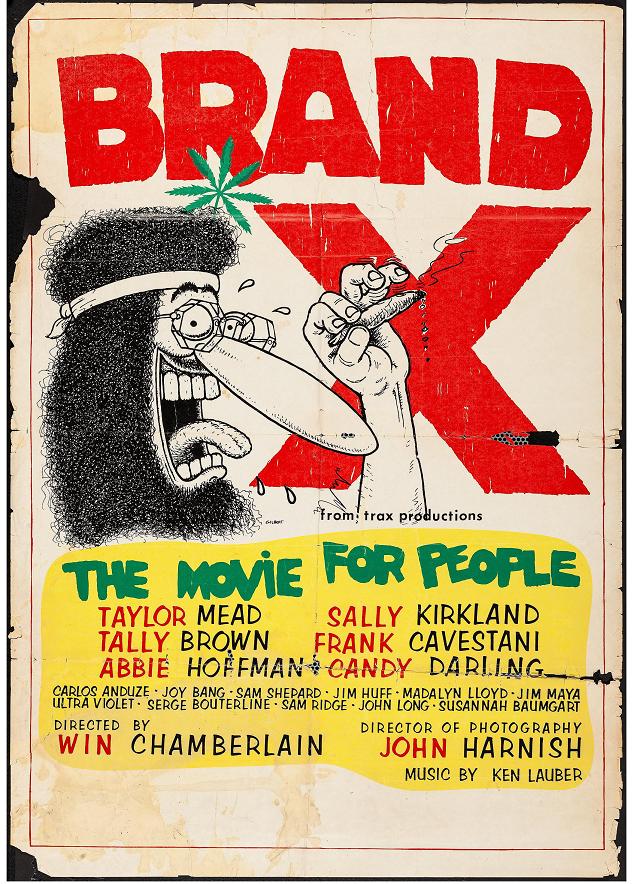

I mention the year of BRAND X’s release solely to note that it celebrates its 50th anniversary today, as the film may as well have “1970” embossed on every frame. From the nature of the humor involved to the cast to the poster art by underground comic artist Gilbert Shelton, BRAND X places its 1970ness at ground zero, and its best watched while considering both the time period that proceeded it and the similar nature of films and television that it may have indirectly inspired. Watching it with 2020 vision (sorry), BRAND X is a fascinating look into a very specific time, place and mindset, and trying to watch it without this context would be an exercise that likely wouldn’t leave you in more than stunned silence.

Written and directed by artist and writer Wynn Chamberlain, BRAND X was inspired by Chamberlain’s disgust with the banality of daytime television. The film is formatted much like later efforts such as TUNNELVISION, THE GROOVE TUBE or AMAZON WOMEN ON THE MOON, with fake television programming such as a talk show, game show, and workout show, as well as bizarre advertisements. However, the content itself is less based in actual jokes than bizarre riffs and tangents that poke at the establishment mores of the era.

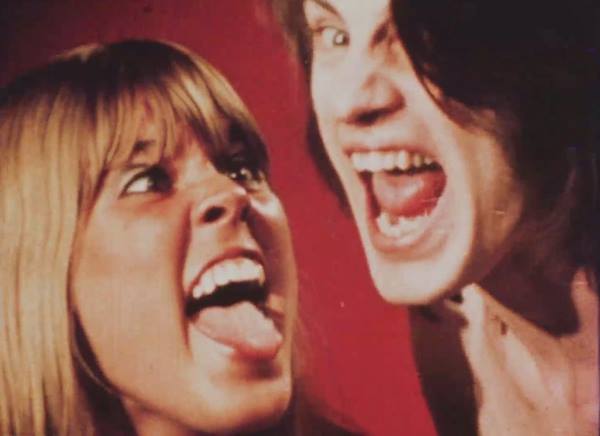

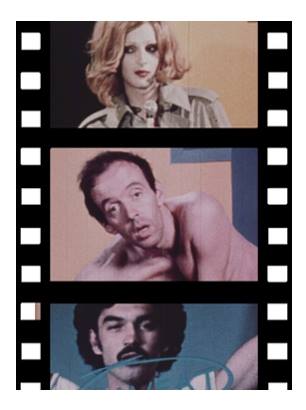

A talk show host (Warhol star Tally Brown) has a group of bodybuilders disrobe. A game show asks contestants to guess a person’s sex. A newscaster reads directly from the newspaper, outraged by the rampant nature of homosexuality and nudity. The president rambles on and on and says things like “I don’t think the inevitable will ever happen” while his wife blows bubbles. Blatantly sexual commercials for eating, vibrators, sweat, computer programming and dirt pop up at almost random intervals. If it compares to THE GROOVE TUBE, it’s THE GROOVE TUBE via a PUTNEY SWOPE filter, where subversion is the goal more than pure entertainment.

The through line of the film is counterculture performer Taylor Mead, star of Andy Warhol’s TAYLOR MEAD’S ASS – the titular object appears in BRAND X as well – who plays the president, appears in a hospital bed, does a workout routine and pops up in a majority of the film’s scenes. The cast also includes up-and-comers like Sam Shepard and Sally Kirkland, Warhol stars Candy Darling and Ultra Violet, LA Weekly founder Frank Cavestani, and Yippie prankster Abbie Hoffman, who bathes in money. (The IMDb lists Pat Paulsen as the president as well, but I didn’t spot him, and Mead clearly plays the president.) While Chamberlain wrote the film, it’s likely that a good percentage of the dialogue, especially Mead’s, was improvised, and it shows in the best possible way, giving a glimpse into the era more authentic than any rehearsed dialogue would have.

Considering the cinematic atmosphere of the time, it’s not too surprising that BRAND X received favorable reviews and good word of mouth when it premiered in New York City on May 18, 1970 at the Elgin Theatre. What is surprising is that the film basically disappeared shortly afterward, thanks to a snafu with the prints and the rights to the film ending up at New Line Cinema, then mostly distributing underground films to colleges. (Mike White’s The Projection Booth podcast has a great episode detailing its history, including a discussion with Chamberlain’s son Sam.) Even now, after a restoration has been done and the film has re-emerged to appear at some festivals and specialty theaters, an easy way to see the film has still eluded potential audiences. Despite the film’s anniversary, the Twitter feed hasn’t been updated in over three years.

It’s a shame, too, as even though BRAND X is a real oddity that may not appeal to a huge audience, it’s certainly a film worth seeing for anyone looking for what subversive humor meant to the east coast counterculture world of 1970. That is, if they can embrace its “dated” nature and connect it to both the time it was responding to, as well as the times that came after it.

- JIM WYNORSKI RETURNS WITH THE CREATURE FEATURE ‘GILA’ - May 1, 2014

Tags: Abbie Hoffman, Andy Warhol, Candy Darling, Frank Cavestani, Gilbert Shelton, Ken Lauber, Pat Paulsen, Sally Kirkland, Sam Shepard, Tally Brown, Taylor Mead, The 1970s, Ultra Violet, Wynn Chamberlain

No Comments