By the ‘nineties, the zombie subgenre was already overflowing in abundance, meaning THE BONEYARD needed to set itself apart from the other films. To make matters even worse, the film is set in a single location, which NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD (1968) had pioneered (and damn near perfected); what’s more, THE BONEYARD was set in a morgue which strides right up on THE RETURN OF THE LIVING DEAD (1985) which was absolutely a perfect film. Against the odds, THE BONEYARD is an amazingly fun and unique little zombie flick made possible by zom-dogs, a ‘Large Marge’ inspired costume that defines “WTF,” and the hero role being fulfilled by a middle-aged, overweight woman — a badass feature that more movies should have.

Alley Oates (Deborah Rose) is a psychic that has fallen into a life isolation ever since the media-circus that sprung from her association with homicide detective Jersey Callum (Ed Nelson). Since cracking a case that lead to pulling murdered children’s skeletons from the ground, Alley has suffered nightmares and when Jersey shows up in her life asking for help on a new case, she initially refuses. After deciding she couldn’t live with the guilt of not helping, Alley joins the investigation on her own terms and joins Jersey and his partner at the understaffed mortuary in order to psychic up some answers. When she realizes that the corpses in the basement aren’t quite dead — but not quite living — a fight for survival ensues as means to escape is blocked and the living start to lose more than just their lives.

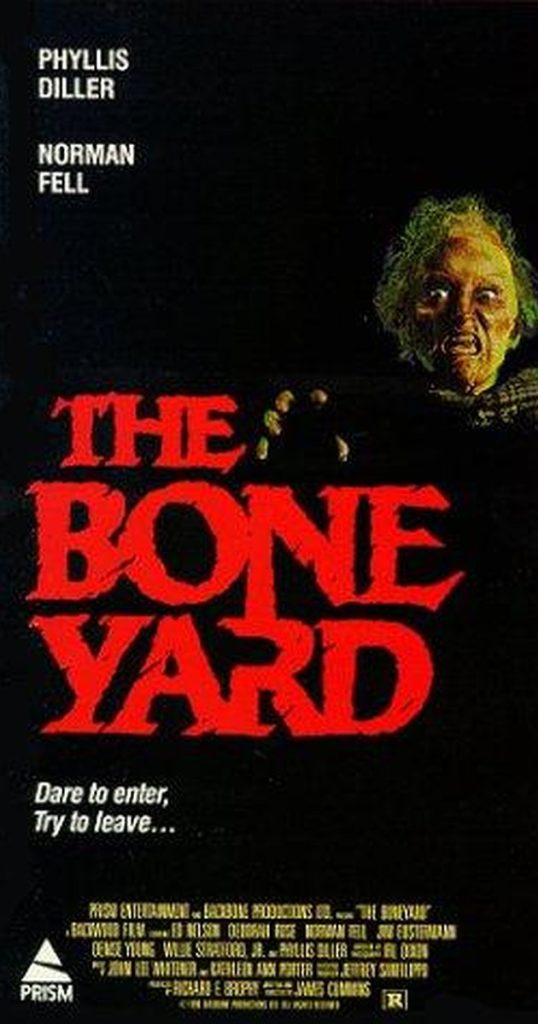

Physical effects supervisor Ray Bivins, working from designs by writer/director James Cummings (who did creature work on HOUSE (1985) and ENEMY MINE (1985), brings to life some amazing creatures. The zombie ghoul-children look appropriately disgusting and move with a lithe step that calls ahead to the terrifyingly fast zombies of 28 DAYS LATER (2002) and DAWN OF THE DEAD (2004). The ‘Large Marge’ looking creature is both strangely unsettling and roll on the floor laugh worthy at the same time — not to mention the helluva punch it packs. Finally, the zom-dog, perhaps a spoiler but the cover artist wisely knew it’s allure was more important, is one of the most balls-to-the-wall insane creatures to just appear in a film; it’s a good puppy gone bad in the best way — CUJO (1983) ain’t got shit on Floofsoms.

As crazy as the creatures make THE BONEYARD, the film truly stands out for it’s casting of Deborah Rose in the hero role. It’s almost insulting to have to write about the marginalization of middle-aged women or overweight actors and actresses; the fact that these roles don’t exist is a problem that has yet to be addressed and is a negative against the film industry. Deborah Rose is treated with respect by the movie — that’s not to say that the mean character doesn’t get a barb in, but that the movie itself never condemns, criticizes or insults her in any way; instead we are treated to a strong woman with a compelling character and arc that never alienates viewer identification (a justification that Hollywood has used for its lack of casting that, frankly, is bullshit).

However, everything’s not just Vanilla Nice with THE BONEYARD. It has it’s problems, too. Chief among them is the choice to have the villains (the sorcerer and family responsible for the creation of these zombies) be asian for no reason. The only asian characters in the film are portrayed as evil, the creatures are not tied to any mythology that would justify this choice and, absolutely worse of all, the sorcerer is played by a white dude as an Asian character. It’s absolutely unnecessary, offers nothing to the film and feels like something out of a Fu Manchu feature. The second problem that THE BONEYARD forces the viewer to confront is its portrayal of survived suicide as something that can be easily passed. An early scare is produced in an autopsy cadaver waking up to reveal that she is still alive, having failed her attempt at suicide. When told she can get passed it, the character insists that it’s not that simple, and the film seems ready to acknowledge suicide as a complicated issue that takes time and understanding rather than a quick way to write in another character; only, the film then drops that thread entirely and the event is never again brought up and the ending implies a happy life for the character now that she has met a man — a cheap ploy to bring in another character and a love interest for Jersey’s partner, the suicide thread comes across as juvenile and uneducated.

Like the sequels we previously looked at, THE BONEYARD is able to an overcooked idea and inject new life into it. It’s everything that Cinéma Dévoilé treasures most, found at the bottom of the barrel of popular culture; a sign that the ‘90s didn’t mark a decline in the horror genre but proof that people just weren’t looking in the right places. Join me next week as we take a look at childhood corrupted in DEMONIC TOYS (1992).

Tags: Cinema Of The Devoid, Deborah Rose, Demons, Ed Nelson, Horror, James Cummins, Norman Fell, Phyllis Diller, Ray Bivins, The 1990s

No Comments