I once read an interview with the author of Twilight where she proudly claimed to have never read Dracula. In case you’re wondering why people like myself — who are normally far more open-minded about trash culture — have no respect for the Twilight phenomenon and won’t bother to read the books, this is one very strong reason why.

Openly admitting to having written a book featuring vampires without having bothered to read Dracula is like making a movie at this point in time about the Italian-American mafia without having seen THE GODFATHER, like making a movie about vengeful great white sharks without having seen JAWS, and [absolutely, I’ll go there] like telling the story of Jesus Christ without having ever read the Bible.

In my own possibly over-heated opinion, it’s a kind of plagiarism to use someone else’s ideas without acknowledging the debt. Of course, Twilight isn’t a true vampire story to begin with; instead it’s just the most popular example of an improbably popular genre that should be called “vampire romance.” It belongs on the shelf with the romance novels rather than in the horror section, but that’s another rant for another time.

To re-read Bram Stoker’s classic 1897 novel Dracula, one will quickly see how fresh it feels, and how well deserving it is of its reputation and its influence. There have been tales of vampires (or their equivalents) in the majority of cultures in the majority of corners of the world for the majority of human existence. What Stoker did with Dracula was to marshal together some clear-cut rules and common traits of vampires, inject some amount of research and historical reference, and utilize his own character-building ability to create the most clearly defined vampire character of all time in Count Dracula.

If Count Dracula wasn’t such a commanding, imposing, ominously memorable figure in the novel bearing his name, then Dracula the novel couldn’t have been the touchstone that it is in horror literature. In other words, Stoker’s greatest achievement was to distill all of that cross-cultural mythology into one iconic character. Creating a true icon is one of the most difficult things a writer can do, because it can’t be forced and it has to come from a genuine place of character impact, but when it happens, an iconic character can lift the entire genre around him/her to prominence. (Maybe that’s why werewolves are perennial also-rans – there’s no one iconic werewolf character to center the genre. But that’s another subject for an even longer essay.)

A couple observations struck me as I made my way through the book this time. One was the intense ruthlessness and cruelty of the Dracula character. There is no trace of humanity or sympathy within him; he wants what he wants and has no reservations about taking it. This, more than anything, is where today’s “vampire romance” trend diverges from its roots in horror.

The vampire mythology has a natural eroticism to it – the act of feeding has always had a sexual element in its description – but Dracula, as portrayed in in Stoker’s novel, is hardly a romantic figure. If anything, he’s a sexual predator. While his conquest of young Lucy Westenra has clear sexual overtones in its description, it is disturbing at its core and its results are clearly tragic. Count Dracula is by far the dominant character in Dracula, but you don’t read it wishing for anything other than his demise at the hands of the novel’s heroes.

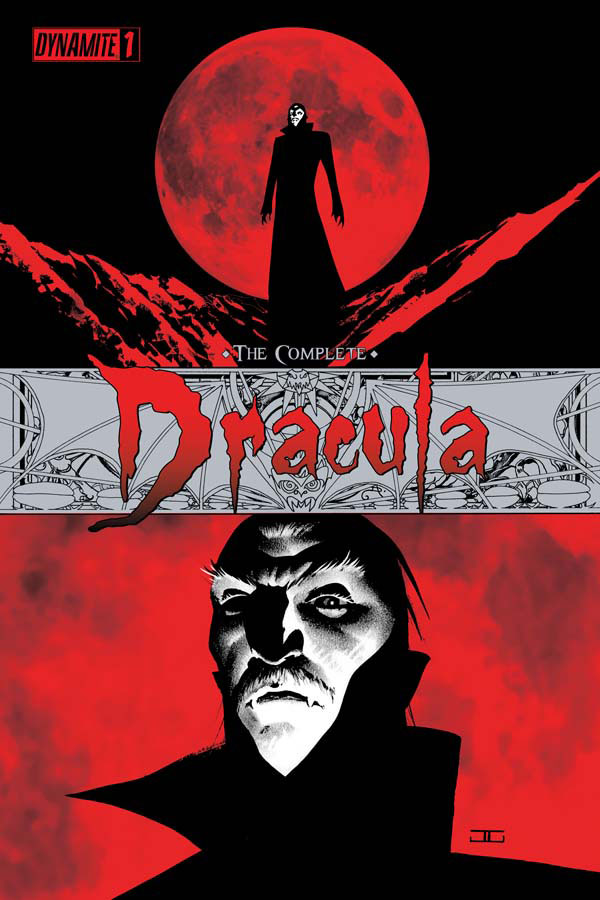

Another interesting observation to me is that very few visual interpretations of Count Dracula have come particularly close to his appearance as described in the book. There have been so many wonderful and unforgettable Dracula designs, but strangely, none of them have looked much like this: “…A tall old man, clean shaven save for a long white moustache, and clad in black from head to foot, without a single speck of colour about him anywhere.” So in Stoker’s mind, Count Dracula would look like James Coburn with the wardrobe of Johnny Cash. I kind of love that.

This drawing by the great comic book artist John Cassaday comes the closest to that description of any I can recall, but of course it’s still great to have all of the different looks that cinema, television, and comic books have afforded us throughout history, from Bela Lugosi’s iconic caped slickster, to Gene Colan’s ferocious drawings for Marvel in the 1970s, to Gary Oldman’s “Aunt May” rendition.

I was also surprised to be reminded of the way that the story is structured. Dracula is an epistolary novel, which means that it is made up of fictional correspondences and communications – a common storytelling choice that used to be popular in antiquity but was way out of style in the past century, until the current horror boom with books like World War Z which use a comparable “oral history” format. It’s a fascinating choice on Stoker’s part to have Count Dracula’s personality and exploits recorded and reported by a group of protagonists, including Jonathan Harker, his fiancée Mina Murray, close ally (and initial courter of Mina’s friend Lucy) Dr. Seward, and of course that infernal Van Helsing.

It’s also intriguing to see how the book is split up into phases; the first chunk of the novel is largely drawn from Harker’s journal, and depicts his initial encounter with the Count in Transylvania; the next chunk involves Mina’s correspondences with Lucy, wherein her concern about Jonathan is expressed, and where we also first hear about Lucy’s suitors (Seward, Quincey, and Holmwood, who later become Van Helsing’s vampire-hunting squad). Then the ship’s log of the Demeter is invoked – the Demeter being the cursed vessel that brings Dracula to England. When the action shifts to England, the story structure shifts again, and the novel’s exchanges toggle between Mina Murray, Dr. Seward, the returned Jonathan Harker, and – not as much as could be expected – Professor Van Helsing.

Abraham Van Helsing is absolutely another key to the success and longevity of Dracula. Harker shows real pluck and resourcefulness and Mina is no precious flower but just as willing to fight as the men, but Van Helsing is the Count’s true opposite number. He is a haunted and determined adversary of vampires, and it’s no surprise that he pops up nearly as many times as Count Dracula in the many iterations of the tale that have transpired throughout fiction and film over the years. (The most memorable was Peter Cushing in the Hammer horror films, the most recent in my generation’s memory was Anthony Hopkins in Francis Ford Coppola’s version in the early 1990s. We’ll not speak of Hugh Jackman around here.) The creation of Van Helsing is another of Stoker’s masterstrokes – just as a good hero is best defined in opposition to his worst enemy, so too is the greatest villain best tested by a strong hero. You need a Captain Ahab to pursue Moby Dick, you need a Joker to forever plague Batman, and you need Van Helsing to constantly thwart Count Dracula.

However, the character that stuck with me this time around was the poor, unfortunate Renfield. Renfield is a patient of Van Helsing’s friend Dr. Seward, who runs a lunatic asylum. Renfield acts as kind of a predictor of Dracula’s comings and goings; his ravings increase or subside depending on what the vampire is up to. Renfield is a tragically memorable wretch who eats spiders and flies and figures into some of the most sad and disturbing passages of the book. It’s funny; when I read The Lord Of The Rings, the most resonant character to me was Smeagol, a.k.a. Gollum, a.k.a. that freakish creature who’s obsessed with and tormented by power. It’s just so perceptive on the parts of Stoker and Tolkien, as they manage to conjure characters of the most abject evil and the most resolute virtue on either side of the central battle, to also acknowledge those pathetic figures who face similar trials and fall short of either extreme. Not everyone can be purely good or powerfully bad; in fact few are – most of us, when placed into such apocalyptic scenarios, would fall somewhere in the middle, and the weaker among us would be ruined by the experience. Some of the more famous portrayals of Renfield throughout Dracula history have been Dwight Frye (also known as the hunchback ‘Fritz’ from the James Whale FRANKENSTEIN), Klaus Kinski, and Tom Waits. That’s one interesting dinner party right there.

Since it started out as a bit of a grumble, I’m happy that this article has turned into such an enthusiastic celebration of a classic work of literature. Dracula isn’t quite flawless; it does have its repetitive passages, particularly when Mia Murray and Prof. Van Helsing get into their mutual admiration routines. However, that is a small complaint when weighed against the harrowing Transylvania scenes, the atmospheric Demeter sequence, the tragic loss of Lucy Westenra, the inspiring gathering of the vampire hunters, and the still-affecting-despite-it-all afterword. Bram Stoker’s novel remains one of the most influential books ever written. Dracula casts a long shadow, and all of us who create and enjoy horror stories are still standing in it.

— JON ABRAMS (@jonnyabomb).

Much of the art I collected off Google Images from this piece came from either the work of the legendary Gene Colan, or new comics great Becky Cloonan. There’s plenty more out there, and I highly recommend seeking it out!

- [THE BIG QUESTION] WHAT’S YOUR FAVORITE FEMALE ENSEMBLE IN MOVIES? - July 22, 2016

- [IN THEATERS NOW] THE BOY (2016) - January 24, 2016

- Cult Movie Mania Releases Lucio Fulci Limited Edition VHS Sets - January 5, 2016

Tags: 31 flavors of horror, Bats, Books, Horror, Literature, vampires, Wolves

No Comments