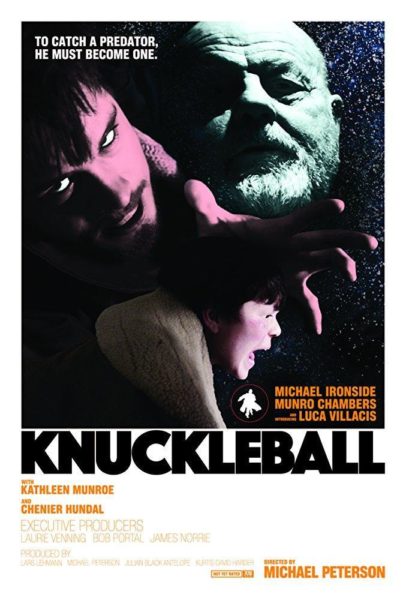

KNUCKLEBALL, a Canadian thriller from Michael Peterson premiering at Fantasia this week, is the story of Henry, a 12-year-old boy played by Channel Zero’s Luca Villacis. Taken to the remote farm of his grandfather Jacob (Canadian genre film icon Michael Ironside) to be watched while his parents attend a funeral out of town, Henry’s more interested in playing video games on his phone than dealing with his grandfather’s chores. Still, the two bond quickly in a gruff, traditionally masculine sort of way, over a mutual love of baseball.

Henry’s experience takes a turn, however, when Jacob dies, and Henry attempts to find help with next-door neighbor Dixon (TURBO KID’s Munro Chambers), a shifty young man with a questionable relationship with Jacob and the owner of the only working phone in the nearby area. Dixon turns violent, and Jacob must defend himself in a twisted version of HOME ALONE as his parents attempt to return after receiving a cryptic voicemail.

Films geared for adults that have pre-teens as their lead characters can be a bit of a crapshoot. Kids in films, obviously not being written by those in their general age range, can easily come off as feeling artificial–too precocious, too resourceful, too annoying, and rarely acting similar to what an actual pre-teen would be acting like in the same situations.

It’s easy, then, to be leery of KNUCKLEBALL. Thankfully, Peterson and Villacis avoid any of the usual pitfalls with a lead child character, and instead Henry comes off like a genuinely believable 12-year-old boy, intelligent enough to be rootable yet occasionally flawed in his decision-making and reactions to others in a genuine way that someone that age would be. It’s a pleasure to watch him on screen, and the character is a good part of what makes KNUCKLEBALL shine.

It helps as well that the world that surrounds Henry is as well-conceived as he is. The relationship between Henry and Jacob is a subtle joy to watch, as two awkward family members who don’t really know how to communicate with each other find common ground. It’s due to the strength of this relationship that the film’s emotional beats in the second half of the film work so well–anything off with the performances or any increase in the minimal dialogue between the two would have made the relationship seem forced rather than real.

In addition, the design of both Jacob’s and Dixon’s houses lend credibility to the world of isolated bachelors having lived alone in their own homes for years. The décor of the houses and even the foods that are prepared for Henry (including the French toast he prepares for himself) feel authentic, giving KNUCKLEBALL a genuine sense of space and time, and placing the audience in the same isolated circumstances as the lead. KNUCKLEBALL has a great sense of a specific location, even if the winter storm that the story keeps referencing doesn’t visibly amount to much.

KNUCKLEBALL doesn’t tread a lot of new ground in terms of story and the cutaways to the world outside of the central location, while well-written and featuring some fine character moments, occasionally distract from the tense atmosphere of the story of an imperiled young man, but it’s still a very welcome entry into the “home invasion” subgenre. In KNUCKLEBALL’s case, that invasion may be far from home and not merely physical, but the results are similarly potent. (Plus, any film that gives Michael Ironside a chance to shine gets my approval.)

–Paul Freitag-Fey (@Dekkoparsnip2)

- JIM WYNORSKI RETURNS WITH THE CREATURE FEATURE ‘GILA’ - May 1, 2014

Tags: Canada, Fantasia 2018, Knuckleball, Luca Villacis, michael ironside, Michael Peterson, Munro Chambers

No Comments