As I begin writing this, it has been roughly seven hours since news broke of George A. Romero’s passing. I try not to mourn the deaths of filmmakers, actors, writers, and other artists I admire. Instead, I try to celebrate their achievements, reflect on what they meant to cinema specifically and art in general, and maybe recommend an overlooked film/book/performance/etc. that they left behind for all of us to discover. I will do that with George A. Romero in this piece, but for a change, I do feel the need to mourn his death. Don’t worry, I will get that portion of this article out of the way as quickly as I can.

I did not start taking film seriously as something more than “just movies” until I was around twenty-years-old. Within a couple of years of my crash course, self-taught film school (a.k.a. the local video store), I had formed my “core four” of directors whose work consistently floored me with their inventiveness, adherence to genre filmmaking that really picked at the scabs of social and political hypocrisy, and sheer entertainment value. Those filmmakers were (in no particular order): Brian De Palma, John Carpenter, Larry Cohen, and George A. Romero. Romero is the first of these giants to fall and it honestly hurts more than I expected.

I only met Romero once. Thankfully, it was not at a convention. He came to my film school, showed MARTIN and did an extensive Q&A. In both the Q&A and brief conversation I had with him afterward, he was as friendly, funny, and mischievous as everyone made him out to be. Then again, I am not a producer, so maybe that was why he was nice to me. I was too shy to ask for a picture with him that day. I have always regretted that.

Like all filmmaking legends, Romero leaves behind a hell of a legacy. While I am sure that most people will focus on his groundbreaking DEAD trilogy (that deserves to be considered a “quadrilogy,” given how well LAND OF THE DEAD has held up), in this piece I want to highlight a few of his lesser-known and viewed films. Sure, even I watched DAWN OF THE DEAD this evening, but through the coming week, I will choose to celebrate his life with some unfairly maligned or forgotten films that confirm how brilliant a filmmaker he was. After all, there was far more to the man’s career than his zombie films and CREEPSHOW.

THE ’70s

SEASON OF THE WITCH

NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD may very well be the best feature directorial debut ever. It is not surprising then that Romero’s follow up, THERE’S ALWAYS VANILLA, an awkward relationship dramedy, failed to make an impression with critics or audiences. Truth be told, it’s a rough film with only a smattering of interesting scenes. He would do a much better job of taking a scalpel to the moral hypocrisy of the suburbs with 1972’s SEASON OF THE WITCH.

Despite its title, SEASON OF THE WITCH is a continuation of Romero’s efforts in THERE’S ALWAYS VANILLA to move away from using the horror genre while still getting across his subversive themes. Once you accept the fact that Joan (Jan White), the bored, lonely, very unhappy suburban housewife at the center of the film only dabbles in witchcraft, but never really does much of anything supernatural, you find a pitch black comedy about the lie at the heart of the American dream.

No matter how nice a car you have, how big your house is, how well-maintained your lawn is, how pleasant you act in public, or how much you try to pretend that the things that are supposed to bring you happiness are not actually bringing you despair, if you are betraying your soul, you will never be comfortable in your own skin. Even worse, you will probably take that unhappiness out on those who surround you. This disquieting message is probably why SEASON OF THE WITCH is not a well-known film.

But when you look at SEASON OF THE WITCH in the context of Romero’s career, it is easy to see him playing with the themes of anti-consumerism and distrust of any sort of hive mind (a subplot finds Joan disappointed by just how much the rigid dogma of the counter-culture mirrors her dull mainstream life) that he would weave into his best films.

THE CRAZIES

A minor classic that is almost too brutal and depressing to watch more than once, 1973’s THE CRAZIES finds Romero putting all his ideas and obsessions together into a cohesive whole that is just as cynical as NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD. In fact, despite the lack of zombies (the mass hordes of “crazies” suffer from a rabies-like virus that causes tem to act out violently), this one feels like a loose sequel to NIGHT. Romero even works into it a fear of the government response to a possibly apocalyptic event through brutal martial law crackdowns and a scientist who could possibly find a cure to the disease if only the military would leave him alone.

Despite being his fourth feature film as a director, THE CRAZIES is rougher around the edges than NIGHT or SEASON OF THE WITCH. But what it lacks in polish, it makes up for in pure anger. This is the work of a young filmmaker who was sickened by his country fighting a pointless war and distrustful of a military that was incapable of dealing with a threat that did not fight fair. It still feels as urgent and ugly today as it did when it was released. If you have not seen it, you should watch it immediately.

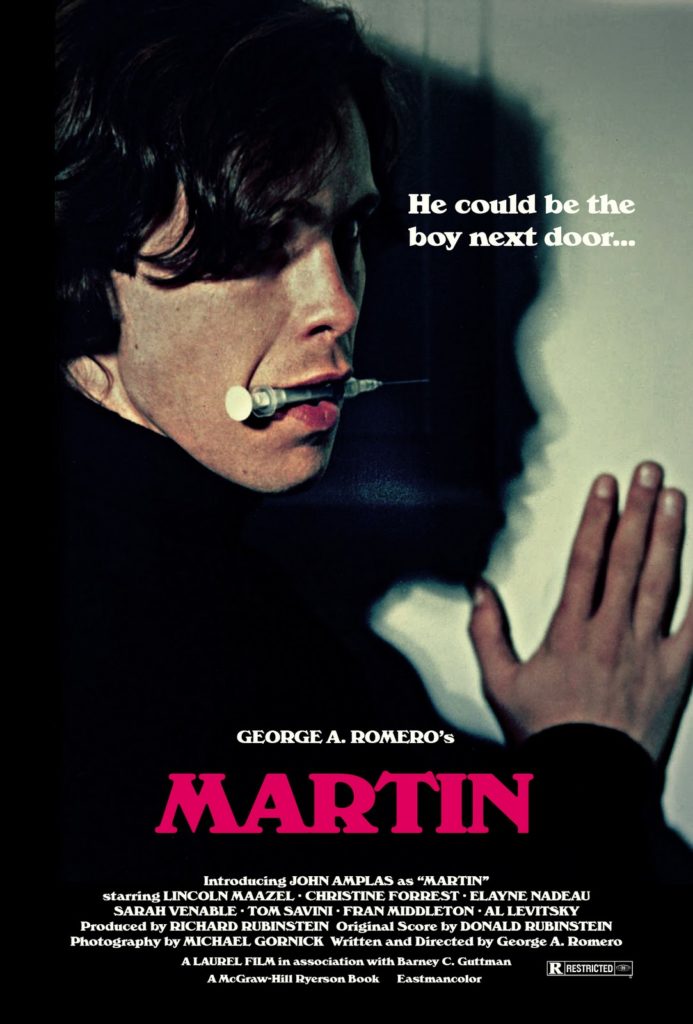

MARTIN

After five years spent working on television sports documentaries (everyone has to pay their bills), Romero returned to feature writing/directing in a major way with MARTIN.

Leaving behind zombie hordes, waves of homicidal maniacs, and housewives dabbling in witchcraft, Romero focused on the loneliness of his teenage titular character (John Amplas, turning in an amazing performance) as he navigated a world of the mundane that clashed with his belief that he is a vampire. But given how dreary life is with his strict, superstitious grandfather (who believes the vampire story and is attempting to save Martin’s soul before staking him) and his unhappy cousin (Christine Forrest—a.k.a. Christine Forrest Romero, beginning her long collaboration with her then husband), you cannot really blame Martin for wanting to believe he is special in some way—any way.

Despite using the traditional set up of a vampire story, Romero steers hard into reality. As Martin says many times throughout the movie, “There is no magic.” Instead of seducing beautiful women, biting them in the neck, and sucking their blood through two delicate holes, Martin drugs them, cuts them with a razorblade, and messily slurps from the wounds, making a bloody mess of the whole process. And yet, despite the horrible things he does, the audience still roots for Martin.

The main way that Romero and Amplas keep Martin sympathetic is that he is clearly a very mentally ill young man. It is hard to hate someone who is so sick. The other reason is that nearly everyone else in the film is a horrible person. MARTIN continues Romero’s presentation of blue-collar Pittsburgh residents as both hard working and narrow-minded. At the same time, nearly every middle or upper class character is shown to be duplicitous; most all of them seem to be having extra-marital affairs with each other that cause complications for Martin but also provide unexpected cover for his murderous activities.

Most importantly, MARTIN also continues to explore Romero’s deep distrust of anyone who allows an institution to think for them. Whether it is Martin’s crazy grandfather believing in old superstitions based in old world Catholicism or the nut jobs that listen to a late night radio talk show Martin regularly calls to tell his life story, there is the message that it is dangerous to place any one person or set of ideals on a pedestal as opposed to thinking for oneself.

Although it was made before DAWN OF THE DEAD, MARTIN ended up being released the same year as the zombie opus. It marked an important turning point for Romero in tone (a dark, ironic sense of humor runs through the film that helps cut some of the nihilism) and collaborators (it was his first film working with Tom Savini, Forrest, and Amplas). That sense of irony and a consistent group of collaborators would continue through Romero’s great run from MARTIN through to DAY OF THE DEAD.

THE ’80s

KNIGHTRIDERS

I am not going to make the case that KNIGHTRIDERS is Romero’s best film. But it is his funniest, sincerest, most surreal, most melancholy, and re-watchable film.

KNIGHTRIDERS gives us memorable sights like men and women in full suits of armor jousting on motorcycles, characters like a self-proclaimed King Arthur-type with a martyr complex (a young and suitably intense Ed Harris), and enough socially progressive subplots to send a Fox News viewer into a foaming-at-the-mouth-rage. With a plot that is a thinly veiled version of Romero’s struggles to keep his creative independence while facing up to the realization that his increasingly bigger films need outside money and producers, the film is also his most personal.

Sandwiched in between DAWN OF THE DEAD and CREEPSHOW, KNIGHTRIDERS was a film that was largely forgotten and ignored. After all, it does not belong to any identifiable genre—never even coming close to be a horror film, there is no gore, its conflicts involve philosophical differences that are hashed out in debate and a few motorcycle stunts between two stubborn but well-meaning factions, and it runs nearly two and a half hours. But in recent years, it has gained a cult following drawn to the sincerity of Romero’s desire to maintain his independence in the changing landscape of American filmmaking.

MONKEY SHINES

After the troubled production of DAY OF THE DEAD (Romero refused to deliver an R-rated film and his budget was slashed), seemingly each film became a struggle to get made. MONKEY SHINES is Romero’s first studio film (albeit for tiny Orion Pictures) and, as such, it feels slightly compromised. But even compromised Romero is still worth watching.

Turning away from the graphic horror of DAY OF THE DEAD (arguably the high-water mark for Savini’s make up and gore effects) to a more subtle form of dread, Romero worked from a novel for the first time (adapting Michael Stewart’s book) and reportedly had difficulties with some of the producers (he had to fight to cast Forrest in a small, but important role). The difficulties can be felt in the final product with a couple of stilted performances and editing that feels choppy at times.

But even with as rough as the finished product sometimes is and the lack of overt gore, MONKEY SHINES is still recognizably a Romero film. It continues his interest in the gray areas of ethics in science that were a major component of DAY OF THE DEAD and reaches back to the horror of isolation and loneliness of MARTIN. A killer third act that sticks the landing helps to make this seemingly minor work in his filmography worth checking out.

THE ’90s

TWO EVIL EYES

After the difficult production of MONKEY SHINES, Romero returned to the independent world with a segment in the odd Edgar Allan Poe tribute TWO EVIL EYES.

It is hard to know what to make of this film. Consisting of two one-hour segments—one directed by Romero, the other by Dario Argento, it cannot accurately be called an anthology film, nor is it a GRINDHOUSE-style double feature. Instead, it feels like two horror maestros got tired of fighting producers and teamed up to do a film where they can just let loose, provided the budget was low enough.

While Argento’s adaptation of THE BLACK CAT is expectedly insane and gory, Romero’s THE FACTS IN THE CASE OF MR. VALDEMAR does not feel like the director letting his hair down. That does not mean it is not entertaining. It feels like a deleted segment from CREEPSHOW without the comic book lighting and has Romero’s by-then trademark sense of dark-humored irony. But beyond that, it feels a little thin, especially given the killer run he had finished up with DAY OF THE DEAD and the ambitious chaser of MONKEY SHINES. If you go in with expectations in check, there is still fun to be had.

THE DARK HALF

After CREEPSHOW, THE DARK HALF was Romero’s second collaboration with Stephen King. As an artist who constantly fought pressure to be more mainstream to keep his vision intact, he would seem an ideal choice to adapt King’s novel of a writer fighting his suddenly flesh-and-blood altar ego. But conflicts with the studio (Orion Pictures again) and clashes with his leading man made it another difficult production that again results in a good but compromised feeling film.

The film sat on the shelf for two years while Orion went through bankruptcy proceedings. That kind of delay usually creates bad word-of-mouth for a film, but in the case of THE DARK HALF, it oddly heightened audience expectations. When it was finally released in 1993, it was largely met with a shrug of the shoulders from critics and audiences. Instead of the balls-to-the-wall return to graphic horror that was expected from Romero, it turned out to be a solid, mainstream flick most notable for Timothy Hutton’s impressive performance in a dual role.

Much like TWO EVIL EYES, THE DARK HALF is a film that is entertaining and worth watching, but is better with expectations held in check.

THE 2000s

BRUISER

After the difficult production of THE DARK HALF, Romero spent several fruitless years trying to get various films made. At one point, he was attached to direct THE MUMMY and RESIDENT EVIL. Unable to get anything going in the studio system, he dusted off another of his low-budget, personal scripts and left Pittsburgh for Toronto to make BRUISER.

Much like KNIGHTRIDERS, BRUISER is a direct look into the director’s psyche. But where KNIGHTRIDERS is overall a hopeful film about art maintaining a shaky but useful relationship with commerce, BRUISER is a dark and cynical movie about a man who snaps after years of being under-appreciated and taken advantage of. Given the way Romero was disrespected and ripped off following DAY OF THE DEAD, it’s hard not to see the film as wish fulfillment.

To Romero’s credit, BRUISER is not just a movie by a filmmaker with an axe to grind. While it is violent and absurd at times, it does hold up as a nifty thriller with a very wide streak of humor to it. If it had been made in the ’80s or the late 2000s, it might have even spawned a franchise out of Henry (Jason Flemyng) going around in his creepy white mask taking his revenge. As it stands, it is probably just as well that it was a one off film.

While not as powerful as Romero’s work in the ’70s, BRUISER is just as energetic, subversive, and flat out mean at times. It was also his final really good independent film and feels like the proper place to end this list.

Looking back at the films in this piece, it becomes even more painfully clear just how important of a voice Romero was in American filmmaking. He inspired generations of independent filmmakers to pick up a camera and create something instead of waiting around for someone to hire them to do so. As great as his films are and as much as he has been ripped off in the last fifteen years, his greatest legacy will always be the inspiration he served to every aspiring filmmaker who was blown away upon their first viewing of NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD.

Tags: brian de palma, Bruiser, Christine Forrest, Creepshow, dario argento, Dawn Of The Dead, Day of the Dead, Ed Harris, Edgar Allan Poe, George A. Romero, Grindhouse, Jan White, Jason Flemyng, John Amplas, john carpenter, knightriders, Land of the Dead, Larry Cohen, Martin, Michael Stewart, Monkey Shines, night of the living dead, Resident Evil, Season of the Witch, Stephen King, The Black Cat, The Crazies, The Dark Half, The Facts in the Case of Mr. Valdemar, The Mummy, There's Always Vanilla, Timothy Hutton, tom savini, Two Evil Eyes

No Comments