If someone put a gun to my head and forced me to name my all-time favorite Jack Kirby story, on most days I think I’d have to go with the two-parter from issues #5 & 6 of 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY known in fan circles by its short-hand title, “Norton Of New York.” This pair of comics has anything and everything you could ask for — high drama, deep philosophical questions (specifically in relation to the subjects of individuality, the heroic ideal, the ever-fragile male ego, and the ever-deepening flight of huge segments of the populace into realms of pure fantasy), superb cosmic artwork, dystopian existentialism, even something of an unrequited love story. We’ll get to all of that (and more, I promise) in due course, but first a little bit of backstory for those not steeped in comic book history —

With the near-unprecedented success of Marvel’s STAR WARS film adaptation and spin-off series (which, as it turns out, may very well have saved the company from bankruptcy given that their cash-flow was extremely tight, despite their dominant market-share position at the time, thanks to a series of questionable business decisions), the so-called “House Of Ideas” revealed that they had a dearth of precisely those and actively went searching for other cinematic properties, specifically of the science fiction variety, to exploit in the funnybook pages. The problem was that, unlike these days, there just weren’t that many “blockbuster” films ready-made for mercenary licensing opportunities in the late ’70s — so they had to go back a few years. Thus was born the rather unlikely marriage of Marvel Comics and MGM Studios, who worked together to come up with a deal to publish a “Treasury Edition” (basically a larger, thicker comic with heavy cardstock covers) adaptation of Stanley Kubrick’s legendary film 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY (based, of course, on Arthur C. Clarke’s equally-legendary novel), to be followed by a monthly series — and with Jack Kirby recently returned to the fold, there was probably never any doubt about who the perfect choice to helm this particular four-color ship would be.

Kirby’s “Treasury Edition” film adaptation is breathtaking stuff that makes brilliant use of every extra inch it’s given in order to literally overload readers’ senses with mind-boggling outer space imagery that sears its way into the visual cortex, but I think it’s fair to say that the follow-up comic series takes a little while to find its feet, given that each story, whether told in one or two parts, tells a separate and disparate tale vaguely informed by, but not overly chained to, the film and novel. The first four issues are perfectly fine reads with some amazing artwork, with Kirby wisely concentrating his creative energies on portraying various and sundry situations where the iconic Monolith would act as a kind of cosmic “critical mass” or “wild card” and push a situation (usually of the evolutionary or developmental variety) forward rather than going the dull and unimaginative route of, say, directly continuing the story seen in the film and letting us know “what happened” to Dave, HAL 9000, etc., but it wasn’t necessarily all that clear where The King Of Comics was going with the whole concept.

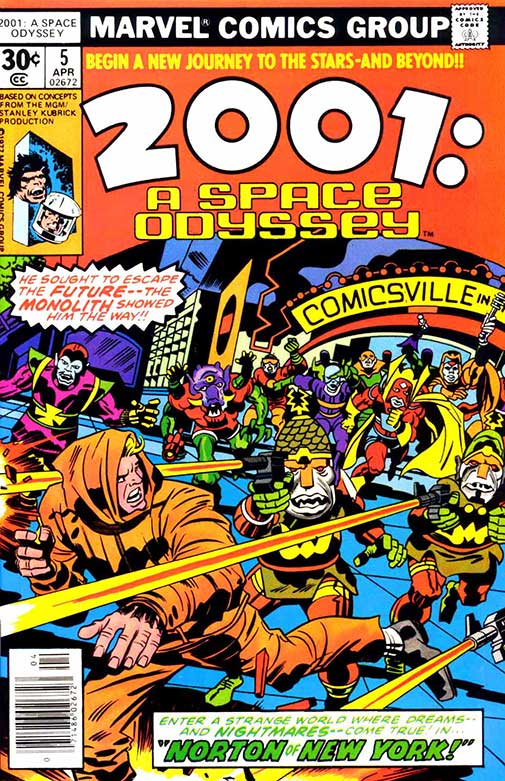

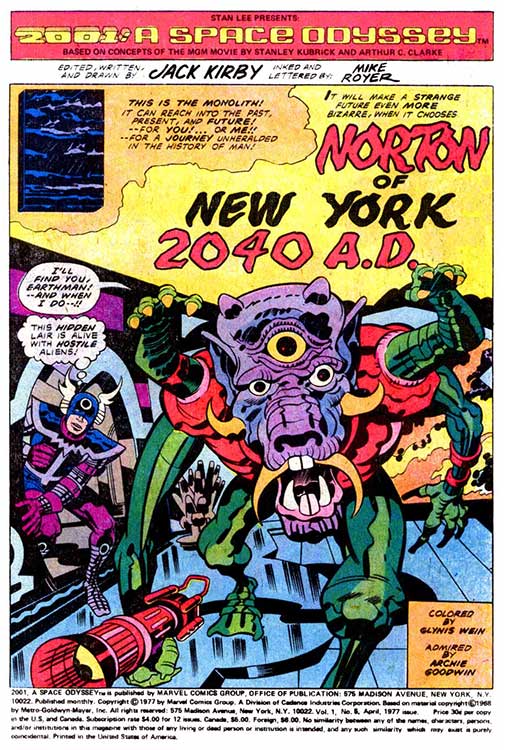

Until issue number five (cover-dated May, 1977 and bearing the story title “Norton Of New York, 2040 A.D.”), that is, when the answer became clear: Kirby was taking us much farther than we ever could have hoped to expect.

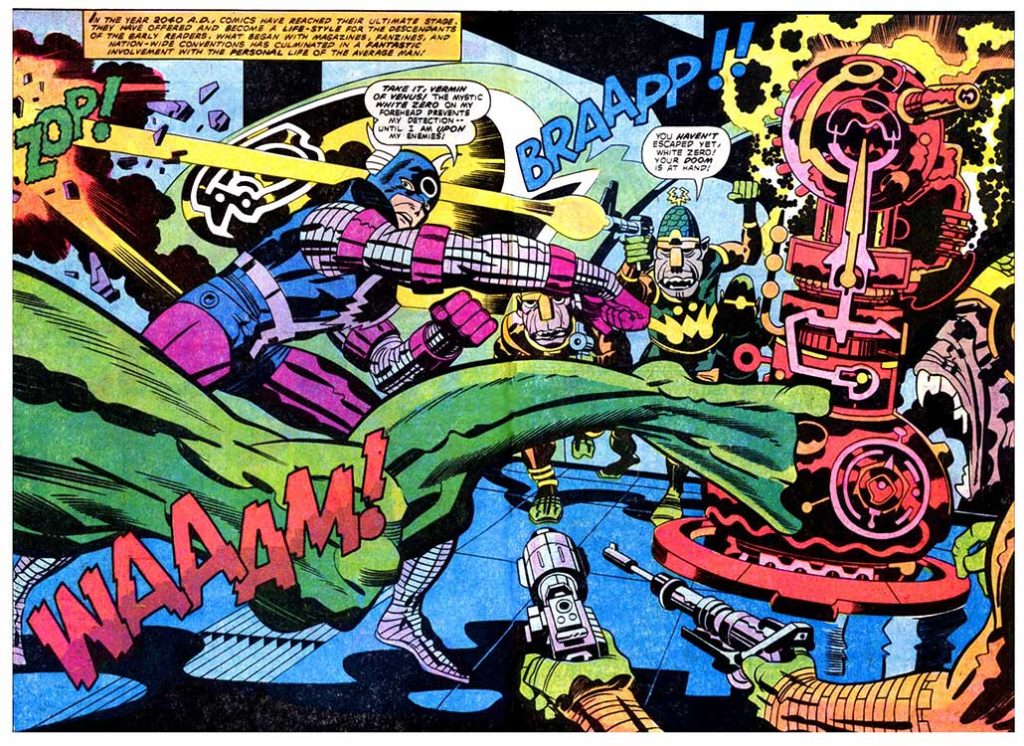

Our saga begins with an ostensible super-hero who calls himself “White Zero” taking on a horde of space monsters in order to save a captured princess, but in a move that some may consider tipping his hand a bit too early, Kirby makes it clear that the whole scenario is a cheap charade — a paid afternoon’s entertainment for bored aficionados of the fantastic at a theme park known as “Comicsville.” The King’s abilities as a Cassandra are well-known, and here he accurately predicts everything from so-called “cosplay” to indoor paintball games to the pathetically immersive nature of today’s various fandoms decades in advance. “Comics have reached their ultimate stage,” the narrative caption-boxes inform us, and “what began with magazines, fanzines, and nation-wide conventions has culminated in a fantastic involvement with the personal life of the average man!”

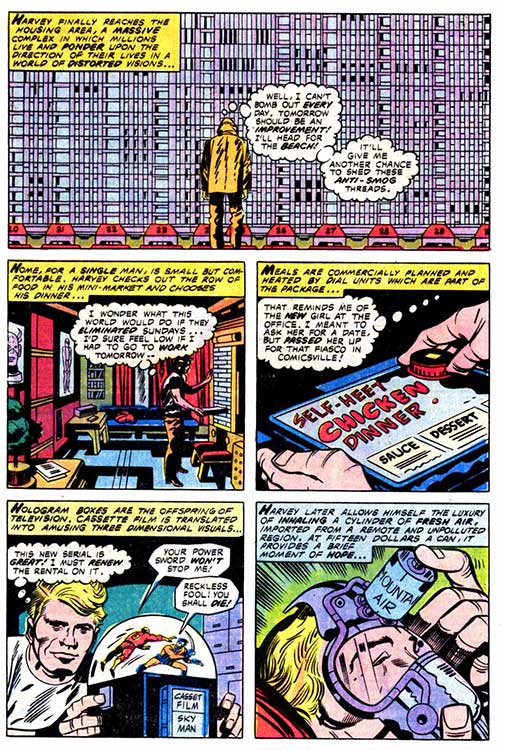

All of which leads one to suspect that the life of “the average man” in the year 2040 is a particularly empty and vacuous enterprise — and so it is. “White Zero” is, in actuality, Harvey Norton, an interchangeable office drone who yearns for more than his post-industrial world has to offer (and has something of a shallow and superficial streak, as his reaction to the “princess” shown below demonstrates) — a yearning that’s exacerbated by his first brief encounter with a Monolith within the confines of his pseudo-heroic “interactive” narrative — but at the end of the day, he still inhabits a New York that’s the logical end-result of soulless consumer capitalism : atomized, isolated people with little to no connection to each other transported, zombie-like, on over-crowded subway trains through a city covered by an “astrodome” and choked with smog to the point that everyone wears the same drab protective suits as they make their way from vapid escapist entertainment complexes like “Comicsville,”enclosed shopping centers, and vitality-sucking corporate workplaces to warehoused high-rise living quarters where they select pre-recorded serial programs (years before steaming services were “a thing”) and vegetate in front of their “hologram boxes” as they consume self-heating frozen dinners and treat themselves, if they can afford it, to doses of packaged “fresh” air.

Kirby’s visual depiction of this all-too-accurate future is equal parts breathtaking, harrowing, and visionary, and the following page communicates everything you need to know even minus its expertly-crafted wordsmithing:

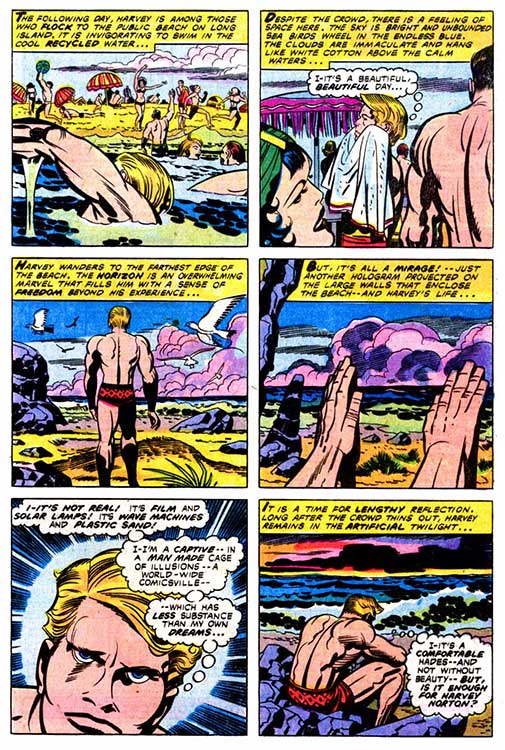

How, exactly, one can escape an edifice of pure spectacle and reach for something authentic that transcends artifice is a struggle that’s been exploited time and again within the science fiction genre, but let’s keep in mind, this is well before THE MATRIX or even THE TRUMAN SHOW, both of which borrowed liberally from the scenario Kirby outlines here. And yet there is still apparently a place for actual nature in the midst of all this, or so it would seem, as Norton is planning to spend his Sunday at the beach — which leads to what is, for my money, the most impactful and devastating sequence in this already-remarkable comic:

The beach, as it turns out, is no beach at all — “it’s not real! It’s film and solar lamps! It’s wave machines and plastic sand!” — but there is, in fact, something very real beyond the illusion: The Monolith, and once again it prods Harvey Norton forward in pursuit of something other, something greater, than the thoroughly homogenized, commodified, hollow world of 2040 has to offer. And hey, before you know it, our guy Harvey is in outer space!

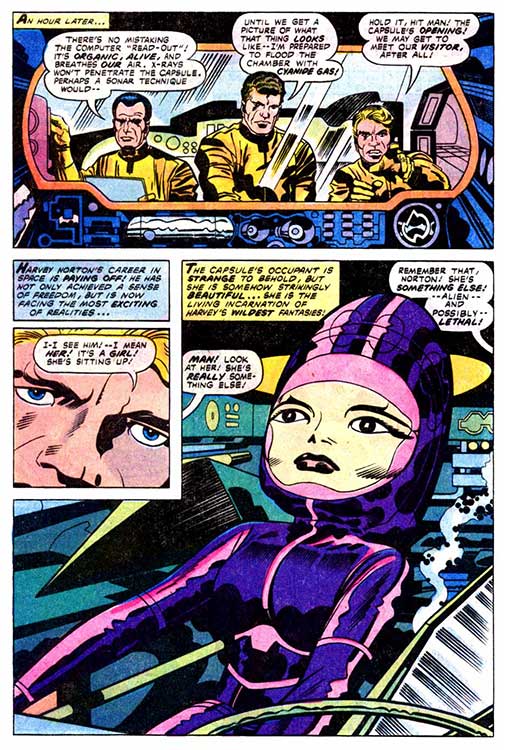

Kirby mentions briefly the two-year training program that his protagonist has to go through in order to earn himself a spot in the “space program,” but in a whiplash-inducing moment, we literally go from the Monolith at the “beach” to “1,000 miles above the planet Neptune,” where Norton and two fellow astronauts are reeling in a mysterious capsule of some sort that they find orbiting in the distant gas giant’s upper atmosphere. They manage to get in on board their ship, where it opens automatically in fairly short order, and within it, wouldn’t you know that they find —

That’s right! An honest-to-goodness “space princess!” And while the obese woman at “Comicsville” may not have been to Harvey’s tastes, this bizarre-looking alien female appears to be right up his alley, and transfixes him immediately. Still, he may not have much time to pursue the object of his affections, because no sooner does he set eyes on her than he and his crew-mates find themselves taking heavy fire by an unseen and unknown enemy! The barrage is short-lived — “a show of power, rather than an attempt to destroy us” — but it’s clear that the “giant battle craft” that has pulled up close to their vessel is populated by beings that have designs on the “princess” themselves. To say that the situation is “fluid” and “up in the air” would be an understatement of mammoth proportions, but as this issue closes, Norton knows that “whatever happens now can only fulfill my destiny!”

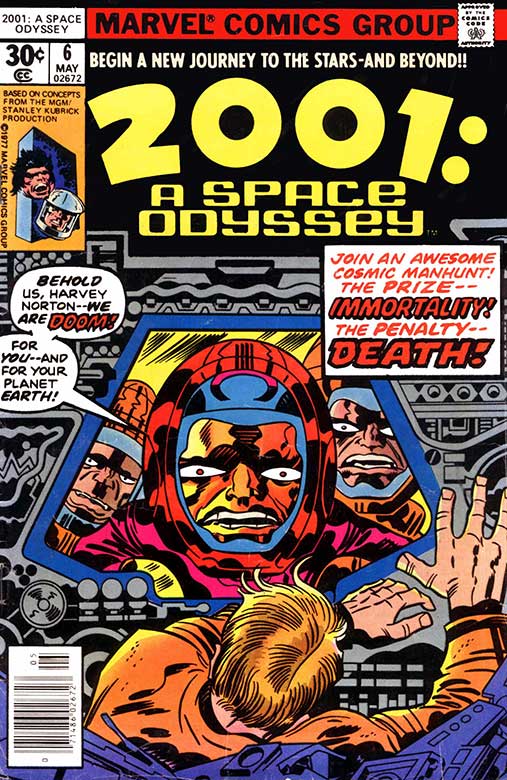

As issue six (cover-dated May, 1977 and titled “Inter-Galactica,” subtitled “‘The Ultimate Trip!,'”) opens up, the detente between the alien spacecraft and Norton’s proves to be short-lived — the cover demonstrates a level of communication between the antagonists that’s never actually achieved, as the spacemen’s language can’t be translated, but whatever — the one-sided firefight picking up steam again within a few pages, and heavier than before. To say that Norton’s head isn’t exactly “in the game” is probably a polite way of putting things, as even in the midst of battle he can’t help but comment that the monstrous ship firing at them is “a comic fan’s dream,” but what he lacks in social graces he more than makes up for in a sort of intuitive understanding of what’s going on that his colleagues clearly don’t share — he just knows, goddamnit, that it’s the “princess” those weird-looking fellas are after, and he’s got a plan to save everyone.

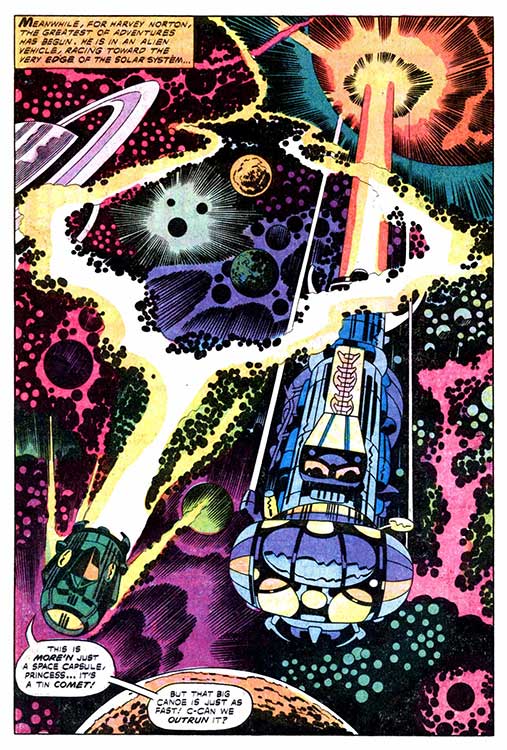

I’ll be the first to admit that what happens next is — how should I put this? — problematic. But as a logical extension of Norton’s so-called “character arc,” it does make perfect sense : with their ship heavily damaged and exposed to the vacuum of space, the three crew members desperately scramble to find their space suits, but in the confusion, Harvey, having figured out that the aliens have a “fix” on the capsule containing the “princess,” absconds with her in an attempt to both draw the aliens’ fire away from his (now former) vessel, and — uhhhmmm — get her to safety. It’s a risky strategy as well as an inherently contradictory one, but over and above all that, it’s also an act of desertion at best, possibly treason at worst. Fortunately for Norton, his fellow astronauts don’t see it that way — one exclaims that “he was a damned hero!” after he reads the hand-written note (no, I’m not kidding) that good ol’ Harv had the decency to leave behind — and the ensuing space-chase gives Kirby a chance to illustrate visionary and awe-inspiring starscapes for page after page, ensuring that kids (and anyone else) who bought this comic in 1977 got way more than their thirty cents’ worth.

As it turns out, the “capsule” piloted by the “princess” proves to be anything but, and Norton’s probably not too far off the mark when he refers to it as a “tin comet.” Still, their pursuers are relentless, determined, and better-armed, and as they reach the very “edge” of the solar system, the “bad guys” unleash “a mass of flaming energy” that Harvey says has “set fire to the universe!” Rather than dodging the inferno, though, the “princess” plunges their craft right into it, engaging the tiny ship’s “star drive” as she does so, which causes them to “leap” both “the solar system — and the galaxies beyond!” Following an incredible journey that sees “Norton’s senses desert him,” the pair finally emerges — well, somewhere. Specifically, here:

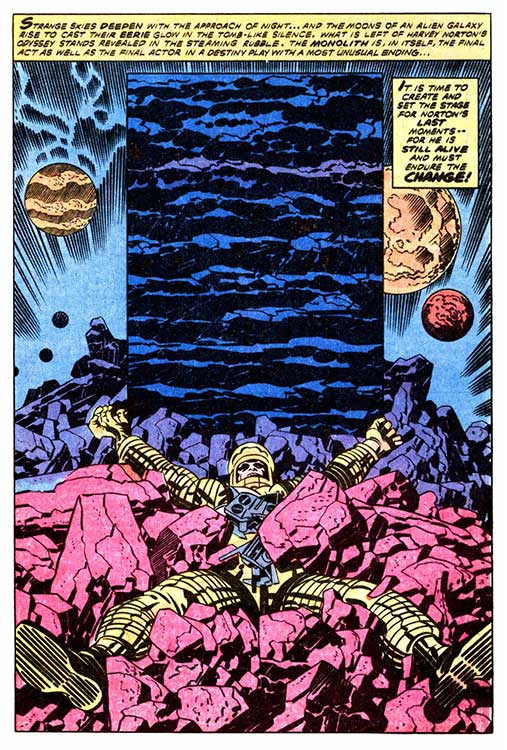

Wherever “here,” is, though, doesn’t seem to be a place where the “princess” is very popular, either — her compact craft quickly draws fire again, and a crash-landing leaves her injured and the two of them sitting ducks. As armed interlopers sweep down upon the apparently-helpless duo, Norton quickly learns how to handle an alien blaster/ray-gun and manages to get his charge to safety — or what passes for it, at any rate, as they enter a cavern that leads to a teleporter (or a “‘sending’ mechanism,” as Kirby terms it) — but if escape is to be had, it will have to be had separately. It’s not for lack of trying to say together, mind you — the “princess” beckons Norton to join in her disappearing act, and he makes it clear he’s eager to accompany her, even imploring her to not to leave without him — “but fate has planned differently for Norton,” and as another fierce blast shakes loose the cavern’s rocky walls, she disappears and something else comes into view behind Harvey as he lies prone and unconscious —

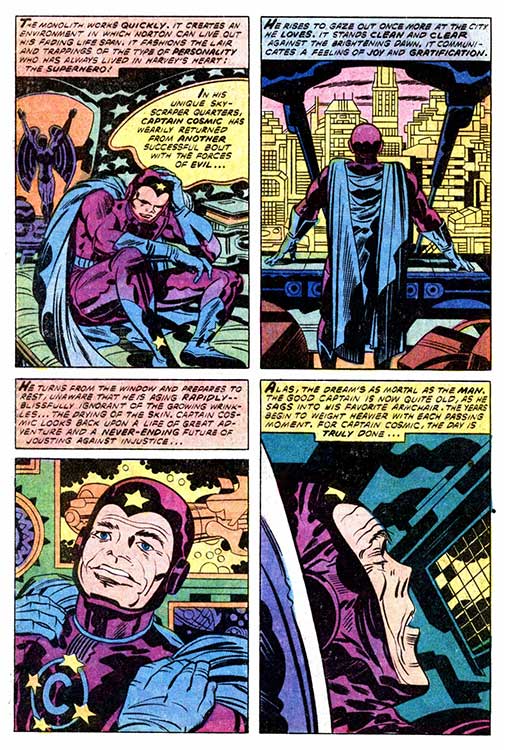

When our “hero” next “awakens,” he really is that — a hero — just as he’s always dreamed of being. His name? “Captain Cosmic.” His domain? A “unique skyscraper” that overlooks “the city he loves” — a city that “stands clean and clear against the brightening dawn,” as opposed to the grim reality of the New York he knows all too well. It appears that Harvey Norton’s deepest desires have all, finally, come true — but his triumph is to be a short-lived one, for, in a manner similar to the magnificent third act of Kubrick’s film, he is aging rapidly in preparation for the “change” that will see him re-emerge as a “cosmic fetus” traversing the universe until it finds the proper time and place to be born anew, a literal “child of the stars.”

What happens next? Well, shit — who knows? The “teaser” at the end of this issue strongly hints that the following month’s yarn, entitled “The Child,” will show the final fate of the Harvey Norton “Star Seed” — but as it turned out, number seven was about another, different, “upgraded” former astronaut altogether. I suppose it can be reasonably assumed, or at the very least intuited, that the reborn/reincarnated Norton had a similar journey, but any way you slice it, “Norton Of New York” is, strictly speaking, a two-part story.

And my, what a two-part story it is. Kirby’s art in 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY numbers five and six, with expert embellishment from his finest (in my view, at any rate) inker, Mike Royer, is bold, expressive, very nearly unbearably imaginative, and the very definition of “next level” stuff — but for my money, it’s The King’s writing that elevates this epic (in the truest sense of the word) tale to “legendary” status. Its flawed protagonist, as the logical extension of the very “fan culture” that his author/creator essentially gave birth to, is at once an easily-relatable “everyman” and a hopeless dreamer doomed to disappointment — until, suddenly, he’s not. And yet, just when it seems his “happy ending” is finally within his grasp, he loses it — only to get it, albeit temporarily, from a source even more unexpected than an actual “space princess.” This time, though, it’s in service of a purpose greater than his own ego gratification — one ultimately beyond his own understanding, and perhaps even ours. For what is one man in the face of a faceless, heartless monoculture? What is one man in the face of his own dreams and expectations? What is one man in the face of insurmountable, odds-stacked-against-him battle? What is one man in the face of an uncaring, but all-knowing, cosmos? These are the questions Kirby asks in “Norton Of New York” — and four decades later, I’m still puzzling out the answers. I heartily encourage you to read these two extraordinary comics and do the same yourself.

Tags: Arthur C. Clarke, Comic Books, Comics, Jack Kirby, Marvel Comics, Mike Royer, Stanley Kubrick

No Comments