Over the course of the past few years, I’ve been of a mind that Simon Hanselmann should dump Megg, Mogg, Owl, and the rest of the gang and do something different. Move forward. Push himself to expand his horizons by letting go of the familiar.

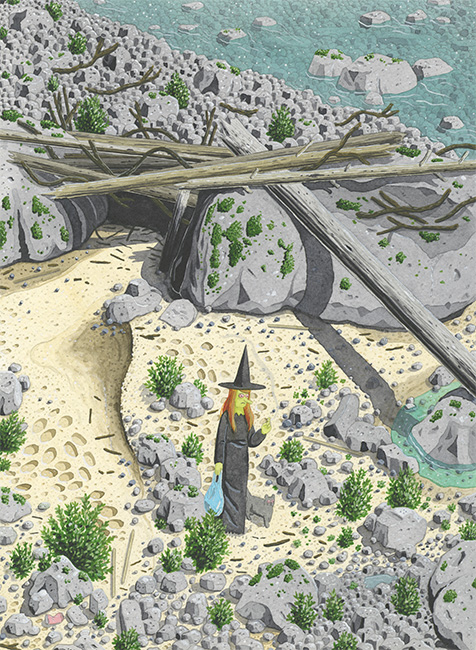

On a purely technical level, he’s definitely been honing his craft — his cartooning has become more precise and refined, while his painting has graduated from the “impressive” to the “magnificently rich and detailed” — but in a larger sense, I felt that he’d been every bit as stuck as his ensemble cast, all this aesthetically-proficient work wasted on dead-end narratives about characters who, by design, were never going to amount to shit. Sure, Megahex was masochistic fun, but Megg And Mogg In Amsterdam was largely more of the same, only in Amsterdam, while One More Year was, well, one more year. I get that his work is focused on the exploits of people (and animals) for whom lethargy isn’t just a “way of life” but is life itself, but let’s be honest — going nowhere is more interesting to read about when it doesn’t seem like the author of a “go-nowhere” narrative is following suit in their real life.

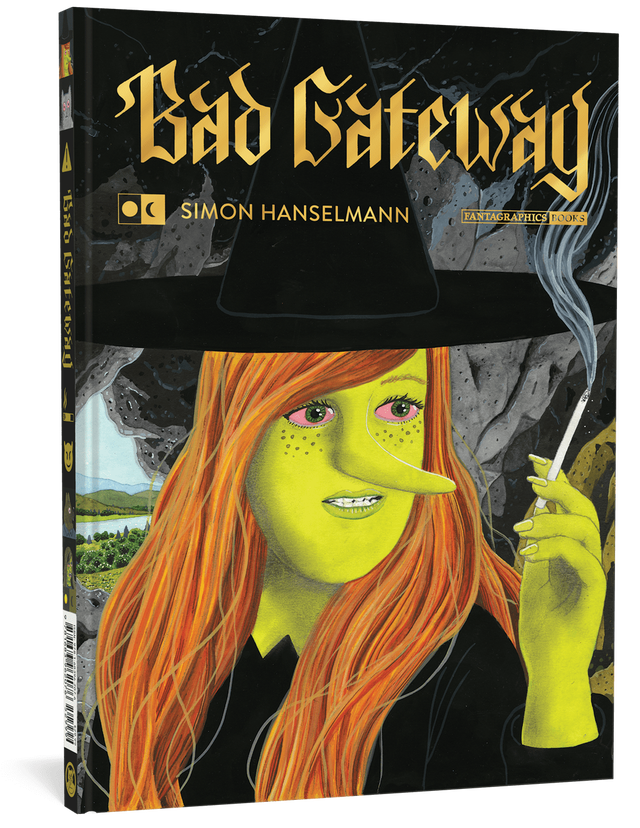

With the release of Bad Gateway a couple of months back, however, all that seems out the window. The physical format itself announces that we’re venturing into new territory with this one, publisher Fantagraphics abandoning the compact size of earlier volumes in favor of an embossed-cover hardback of Eurocomics album dimensions complete with black-as-night gilding on the pages — but that’s just a reflection of the sea change for the darker that’s awaiting readers within.

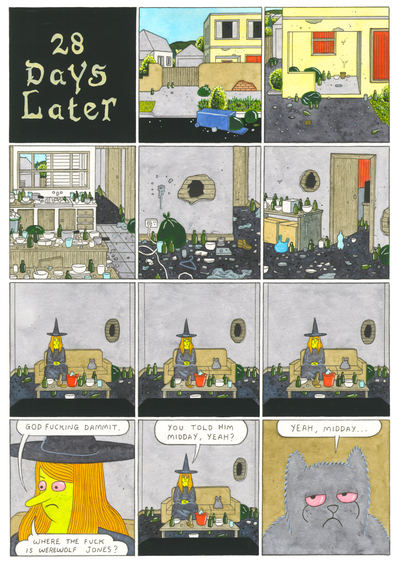

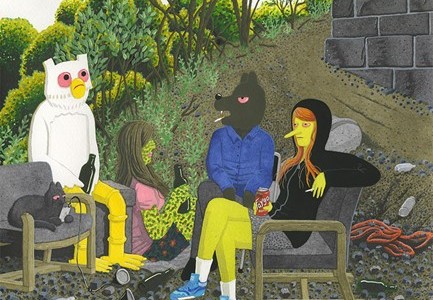

With the long-suffering Owl having finally, and entirely reasonably, decided to fly the coop and his room being being taken over by low-rent dope dealer Werewolf Jones, as well as just the inevitable passage of time, the consequences that Mogg and, in particular, Megg have narrowly been avoiding for so long as they continued their self-destructive downward spiral begin to knock harder at the door. The time has come to grow the fuck up, no matter how poorly prepared these characters are for it — and by choosing to go down this road, Hanselmann has proven me dead wrong. He can, in fact, push himself forward as a cartoonist by sticking with these folks — and if one chooses to view the body of his work in its totality, those last couple of “more of the same” books that I started this review bitching about may have been entirely necessary to set the stage for this one.

Also coming into clear focus is Megg’s status as stand-in for her creator. In the past I’ve viewed Hanselmann’s openness about his mother’s drug addiction and his troubled childhood as almost a cynical “selling point” in much the same way as the egomaniacal-yet-undeniably-talented James Ellroy has exploited the tragic murder of his own mother as a kind of superhero “origin story” to imbue his past with the quality of legend, but when Hanselmann transposes his familial drama onto his characters, the end result is a raw, open, festering wound that leads not so much to any particular moment of catharsis as it does a kind of uneasy and hard-arrived-at resignation. I’d probably prefer to have known nothing about Hanselmann’s upbringing going into this and to have found out about it purely through his art, but hey — it’s his life, and how he chooses to address the issues that shaped him into who he is today? That’s his call.

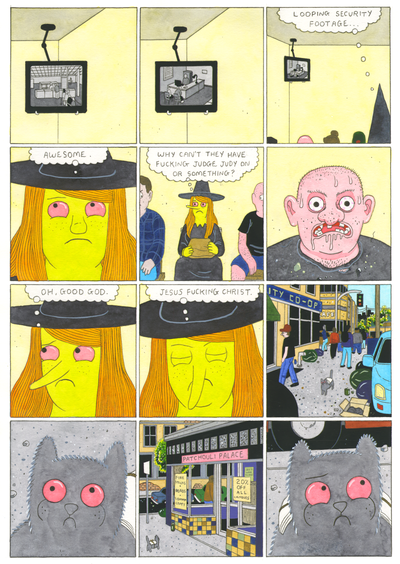

Even with his own “backstory” firmly established in the public consciousness, however, this is still a tough read. Yeah, the juvenile humor is still present and accounted for, but in this new, more expansive context it crosses the threshold from “lame” to “sad,” and the constant question on readers’ minds — “why the hell don’t these losers just get their shit together already?” — is replaced with a deep and unsettling understanding of why they haven’t, sure, but even more crucially why they can’t. And yet…

Like it or not, they don’t have much choice in the matter, and truthfully never did. There’s some emotionally difficult flashback material to Megg’s past on offer here, but more intriguing and ultimately consequential are the hints about the future interspersed throughout that make it clear that this book is in no way the end of the road but, rather, represents the opening of a new and necessary chapter of these lives that we only thought we knew all too well. Some may jump ship at this point, but Hanselmann’s moving beyond the “cheap laughs” crowd and may, in fact, be moving beyond the crowd who are coming into his work looking for any sort of laughs at all. That takes some guts — more, frankly, than I thought he had — and the end result is a book that is both exciting and crushingly depressing in the same way that artists in other media such as Todd Solondz and Hubert Selby, Jr. were once able to simultaneously achieve.

It remains to be seen whether or not all is lost for Megg, Mogg, and their “friends,” but years of self-abuse always come with a price attached, and in Bad Gateway the bill comes due. How they pay it and whether or not they incur another are questions we don’t completely know the answers to yet, but this comic, against all expectation, has me interested in sticking around to find them out.

Tags: Columns, Comic Books, Comics, Fantagraphics Books, Simon Hanselmann

No Comments