I.

I have a recurring dream about a house.

My house, to be specific, but not really: There are extra rooms I’ve never seen before, large walk-in closets that my wife and I both wish we had but don’t, cavernous storage spaces with nothing in them — hell, one time I even discovered a massive interconnected underground aqueduct system that carried sewage (ugghhh) along in a canal but had sidewalks on either side that literally led to every other house in town; houses you could then enter unless folks had their cellar doors locked. Which, for some reason, they didn’t.

What can I say? Dreams are weird, but after a little bit of research, I found that mine are no weirder than most — dreams where your house is different than it really is, where the bus you take to work every morning goes somewhere entirely new, where anything familiar becomes decidedly less so — these are a dime a dozen. They’re as unsettling as they are near-universal, to be sure, and yet —

For all the films, TV shows, and comics that are focused on dreams, how many of them really capture the character of them in a way that feels well and truly authentic? The people in dream-land are always flying around, meeting dead famous people or relatives, re-living childhood experiences — they’re never discovering a hidden hallway in the home they’ve inhabited for 20 years, or finding rotten boards under their porch.

Maybe that sort of thing is simply too prosaic. We like to think that our dreams are adventurous and exotic, especially given that often our lives are anything but, and I get that: We want to feel like our flights of fantasy are well and truly fantastic — and by and large they are, but not in ways we’re necessarily comfortable with.

II.

Chris Reynolds gets it. Since the mid-1980s, he’s been self-publishing, from his home in the UK and to little or no fanfare, comic books set in a shared universe that he calls “Mauretania Comics” — and these stories are the closest thing to actual dreams on paper that I’ve ever seen. They play out in the exact same way that dreams do — there are elements that can’t adequately be described; key events are tantalizingly hinted at but never directly followed-up on; time moves entirely differently, more tethered to events that are happening than to an arbitrary and unforgiving clock; everything is oddly familiar but just a bit off. Nothing is as it should be in these comics, but that realization dawns upon you slowly and incrementally.

Legendary Canadian cartoonist Seth has long been a champion of Reynolds’ work, but to date, the only widespread exposure he’s received was way back in 1990, when Penguin Books issued his long-form story Mauretania in graphic novel format. Other than that, finding this guy’s books — especially on this side of the pond — has been a strictly “hit-and-miss” affair.

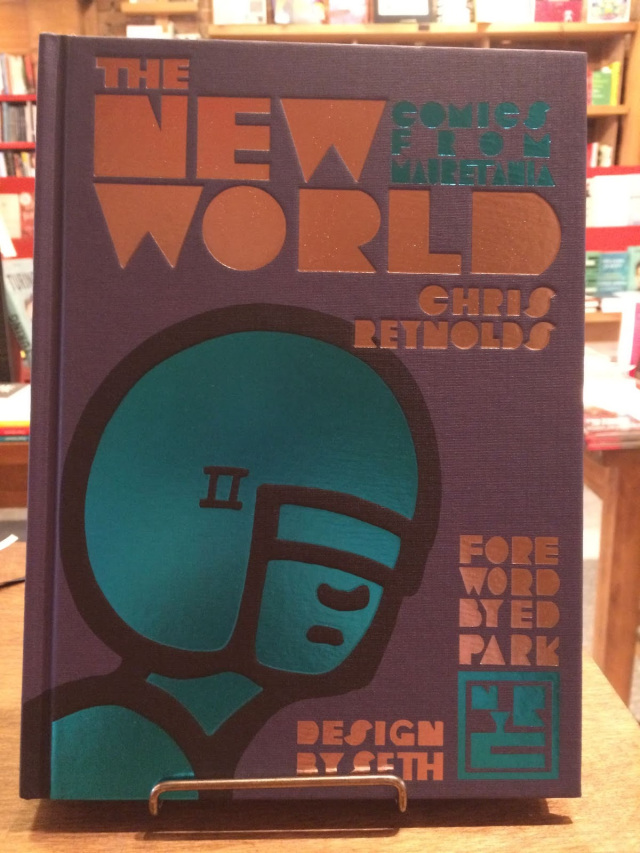

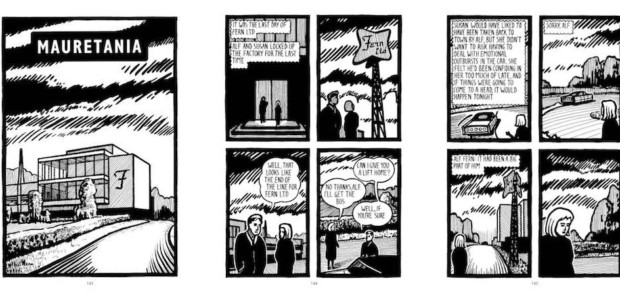

Midway through 2018, though, that all changed: New York Review Comics, with Seth on board as designer and editor and Ed Park along for the ride as author of an introductory essay, released a truly deluxe and fairly comprehensive collection of Reynolds’ print ouevre entitled The New World: Comics From Mauretania that features a gorgeously-embossed clothbound cover, thick, archival-quality paper stock, and crisp, clean art reproduction — most importantly, though, it boasts well over 250 pages of Reynolds’ singular, visionary comics.

The arrangement of stories here isn’t chronological, but that’s perfectly in line with the dream “logic” that Reynolds so skillfully translates and subsequently adheres to. First up is The Dial, a novella-length story that introduces not only the tone, but the various precepts and details that the rest of the stories play off and into (aliens control the Earth, a devastating war of some sort has recently concluded, cars can fly, secret police working for equally-secret masters are ubiquitous, a new religion that the aliens brought with them has supplanted Christianity, Judaism, and Islam, etc.), as well as the cartooning style that not only communicates, but exemplifies the pseudo-reality of this utterly alien, but disturbingly familiar, world: Simple figures illustrated with maximum proficiency but little fuss and muss go about their lives in front of backgrounds short on detail but laboriously accentuated with precise cross-hatching, linework, even shadows. It’s black-and-white, but with a heavy emphasis on the black — so much so that the most natural comparison that comes to mind is to woodcut artwork. But there’s only so much about these proceedings that can fairly be described as “natural.”

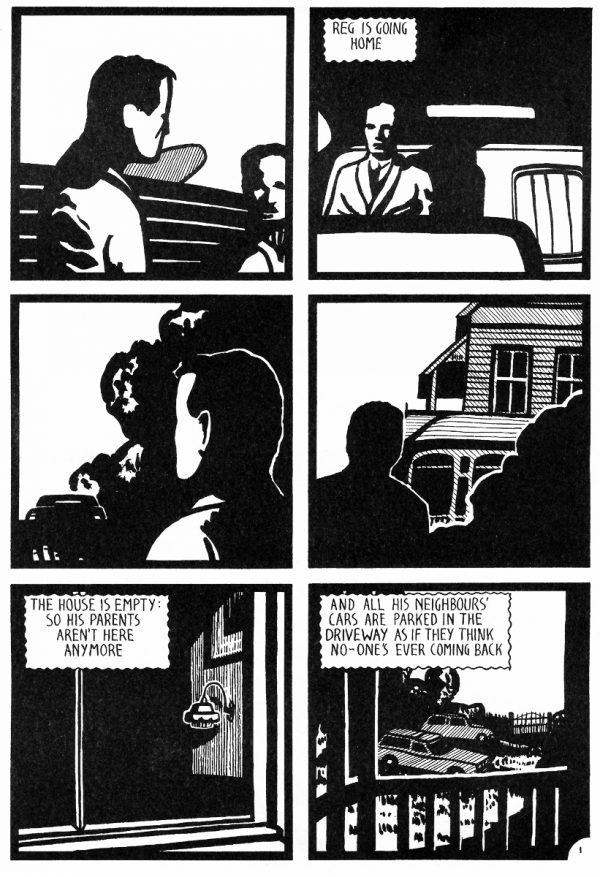

For my part, I’m going with supernatural — isn’t that how dreams always seem? Reg, the protagonist in The Dial, returns from the war to his family home to discover no one lives there any more, but everything else looks okay — until the next day, when he discovers the mining operation underway all around the home, extracting valuable minerals from the ground. Then he remembers the “old” mine works when he was a kid. Why had that slipped his mind previously? Then he meets the foreman, who informs him that they’ll do their best to keep disruption to a minimum, but hey, you gotta expect some inconvenience — and besides, the house is in kinda rough shape. Which it suddenly is. Then it’s off to meet the foreman’s boss, who’s supposed to pay him some money for the hassle his excavation has created for Reg, only this guy says sorry, no cash is coming your way, that house it falling apart, you just need to move and chalk it up as a loss — and when he goes home, wouldn’t ya know, the place has completely fallen to shit. Funny he never noticed that before. And from there on things get even more surreal — in the exact, dictionary definition of the term. Figures that weren’t there before appear in old childhood photos. The house isn’t empty after all, his sister is there. And then his parents. And then, and then — I think you get the idea.

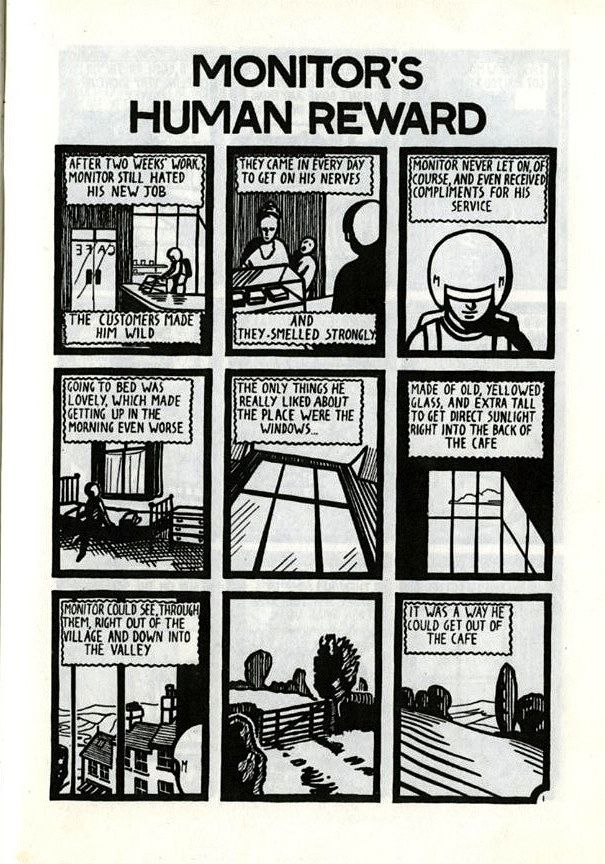

The selection of short stories that follow introduce us to on-and-off recurring characters such as the Cinema Detectives (so-called because they are private eyes who keep an office in a building that used to be a movie theater) and, crucially, Monitor, a helmeted figure of mysterious and undefined origin who seems to have a hell of a lot of friends and doesn’t really do much — but nevertheless appears to function, and not entirely unbeknownst to him, as a kind of living, breathing straw that breaks the camel’s back, a ball of “critical mass” if you will, in that wherever he goes, important things simply seem to happen, usually thanks to nothing more than some very subtle direction on his part.

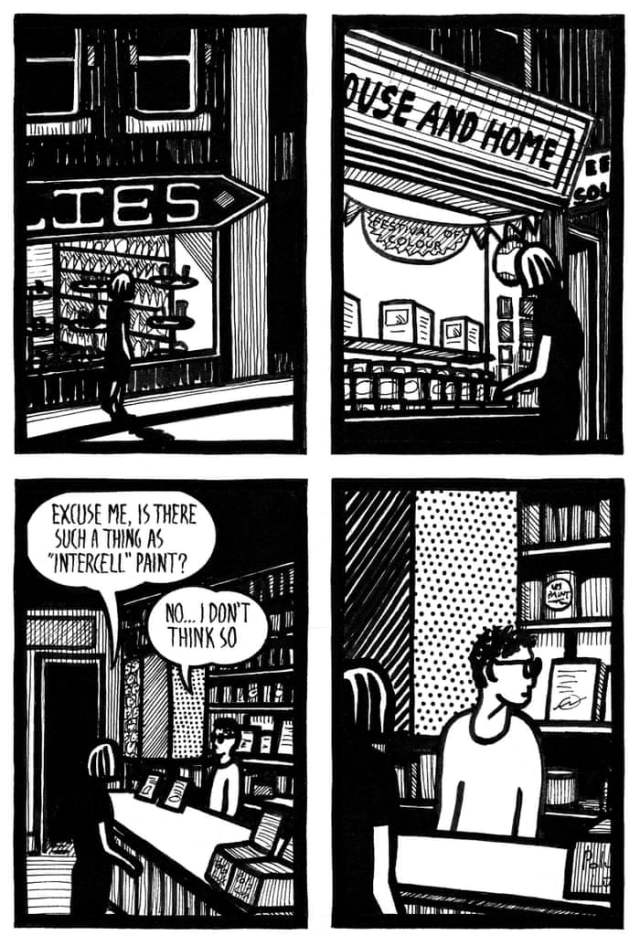

Finally, the back half of the book is taken up with the previously-mentioned Mauretania, a thematically ambitious, but tightly-focused, long form work that dispenses with the rigid six-panel grids of The Dial and nine-panel grids of the short stories in favor of a four-panel grid that gives the art a bit more “breathing room,” but doesn’t alleviate the sense that all this is playing out in a hermetically-sealed world of its own. Monitor’s place here is usurped by a young kid named Jimmy, who has taken up the mantle — sorry, helmet — of his idol (and perhaps, if certain oblique hints are to be believed, father), as well as his mission: He goes from town to town shutting down, by dint of no more than the occasional gentle nudge at the margins, companies that he has decided simply “shouldn’t be.” Not for any environmental or humanitarian reasons, nor on behalf of competitors as a form of industrial espionage, but simply because he’s decided their existence isn’t right.

Jimmy’s sole guide as to what the world should be is a series of unseen “nodal lines” — ethereal connections between places, times, and events that somehow tie them all together into a sort of spider-web grid. He’s opposed in his efforts by the agents of “Rational Control” — a so-called “trendy new police force” — who have even gone so far as to set up “front” companies, CIA-style, in order to monitor the actions of this self-appointed Monitor II. It’s heady stuff, even confusing, yet never difficult to follow — only difficult to fully decipher.

And what’s the point of that, anyway? Certainly mystery genre tropes abound here, but Reynolds never pretends to be going about the business of constructing some grand narrative that explains everything. Yes, there are “eureka!” moments to be had where pieces of the puzzle fall into place, where events dovetail in such a way as to answer certain lingering questions, but the major revelation, the missing link to tying everything up neatly with a bow — it’s always and forever just beyond our grasp, just outside our understanding. Again, much like in dreams.

III.

The Mauretania was a massive British passenger liner that was an engineering marvel of its day, but was scrapped nearly a century ago. Mauritania (note the slightly different spelling) is a sparsely-populated African country that runs from the continent’s southwestern coast right snack-dab into the middle of the Sahara Desert, its name extrapolated from what ancient Roman conquerors called the region. I can’t for the life of me discern what either has to do with Reynolds’ comics nor the imprint he published them under, but again — unsolvable mystery is the lifeblood of this body of work.

Could it be that’s an “answer,” of sorts, in and of itself? Sometimes, more than likely quite unconsciously, Reynolds seems to be utilizing his work to posit a theory that has been making the rounds among the more genuinely radical of anarchist theorists for decades now that some sort of resolution between dream and conscious reality is both possible and, ultimately, desirable — that our bifurcated consciousness is an unnatural development, a regrettable end result of domestication and civilization. I have a feeling that The New World: Comics From Mauretenia may be a work of art that comes from that very place, that Reynolds has somehow been able to reconcile the “real” and the “imaginary” in his mind, and to create stories that are a product of that unified consciousness. I could very well be wrong about that, though — there’s no proving it either way given that specific evidence, either for or against, remains, as always, frustratingly out of reach.

Tags: Canada, Chris Reynolds, Columns, Comic Books, Comics, dreams, Ed Park, New York Review Comics, Penguin Books, Seth, The UK

No Comments