There’s no doubt about it: The post-apocalyptic world isn’t what it used to be. Somewhere, somehow, we swapped out THE ROAD WARRIOR for THE ROAD, and the whole idea of living in an irradiated wasteland, well — it started looking like a lot less fun.

Which, of course, is a change in favor of the decidedly more accurate — yet when the whole idea was fun, nobody had more fun with it than the Italians, who made a veritable industry out of cranking out low-budget MAD MAX knock-offs like ENDGAME, WARRIORS OF THE WASTELAND, or my personal favorite of the bunch, EXTERMINATORS OF THE YEAR 3000. Cartoonist Gipi has apparently chosen to ignore this, let’s face it, less-than-proud tradition of rip-roarin’ adventure set after world’s end laid down on celluloid by fellow countrymen Joe D’Amato, Enzo G. Castellari, Giuliano Carnimeo, and others, and instead is giving us the straight dope: No souped-up muscle-cars, battles over gasoline, and scantily-clad women in cages for him — rather, the vision he lays out in his 2016 graphic novel Land Of The Sons (translated into English for the first time by Jamie Richards and released last month in hardback by Fantagraphics) is decidedly bleak, as isolated individuals and family units (hence our title) dredge swamps and lakes either for basic sustenance or “goods” with which to barter to achieve same. Mutant survivors still roam this hellscape, of course, but they don’t compete in “survival of the fittest”-style bloodsports for the entertainment of those marginally less monstrous (physically, at any rate) than they are, they keep slaves chained in the barn. Larger groups of people band together on occasion and live inside fortified encampments, but they’re under the thrall of neo-religious zealots rather than psychotic would-be “top dogs.” About the only thing Gipi’s post-apocalypse has in common with, say, Castellari’s is that the concept of education seems to have been done away with altogether and nobody can fucking read anymore.

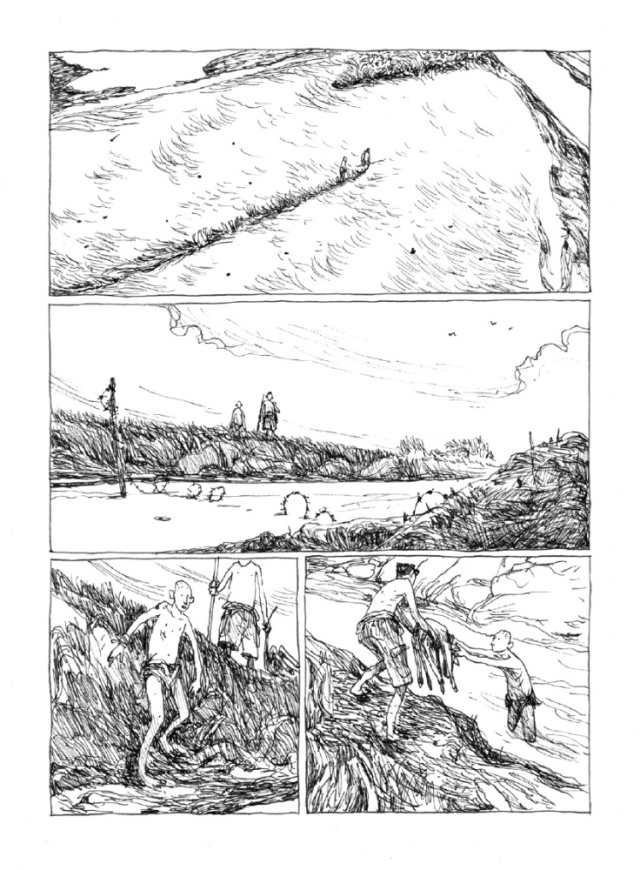

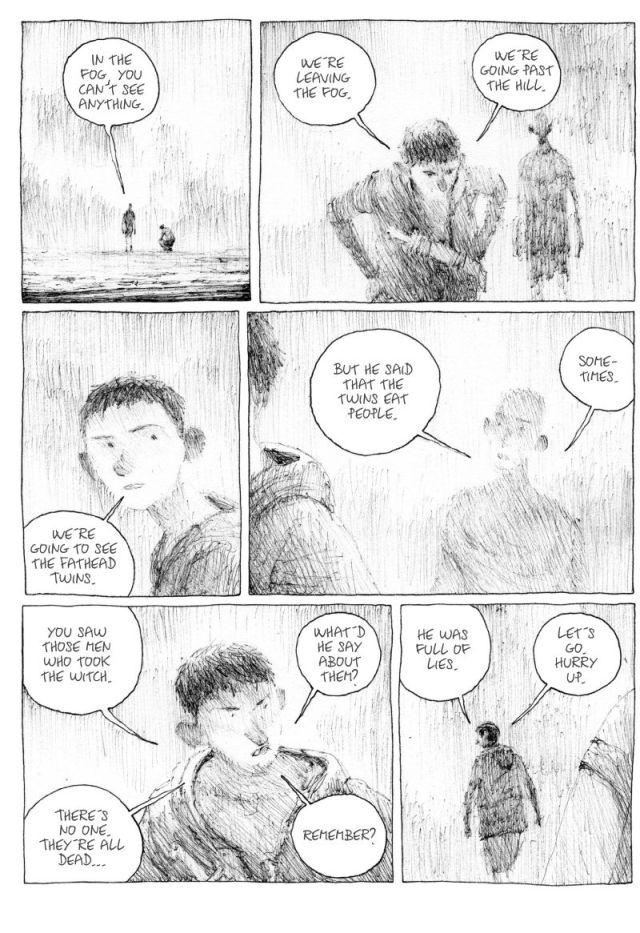

Our “sons” in question here desperately wish they could, of course, as their domineering father keeps what they assume to be a highly-detailed journal not only chronicling the rigors of their day-to-day lives, but also his reminiscences of what things used to be like before the world went to shit, and upon his (slight spoiler alert) demise, their quest to have the book’s contents related to them leads them into harrowing encounters of the type just described, as well as some others — allies prove frustratingly hard to come by as they venture beyond the small confines that represent all they’ve ever known, as does anything remotely resembling peace and quiet, but you know how it goes: when you’re on a quest, you’re on a quest, and if you’re worth you’re salt, you’re not gonna let any obstacles, no matter how dangerous, stand in your way.

Our “sons” in question here desperately wish they could, of course, as their domineering father keeps what they assume to be a highly-detailed journal not only chronicling the rigors of their day-to-day lives, but also his reminiscences of what things used to be like before the world went to shit, and upon his (slight spoiler alert) demise, their quest to have the book’s contents related to them leads them into harrowing encounters of the type just described, as well as some others — allies prove frustratingly hard to come by as they venture beyond the small confines that represent all they’ve ever known, as does anything remotely resembling peace and quiet, but you know how it goes: when you’re on a quest, you’re on a quest, and if you’re worth you’re salt, you’re not gonna let any obstacles, no matter how dangerous, stand in your way.

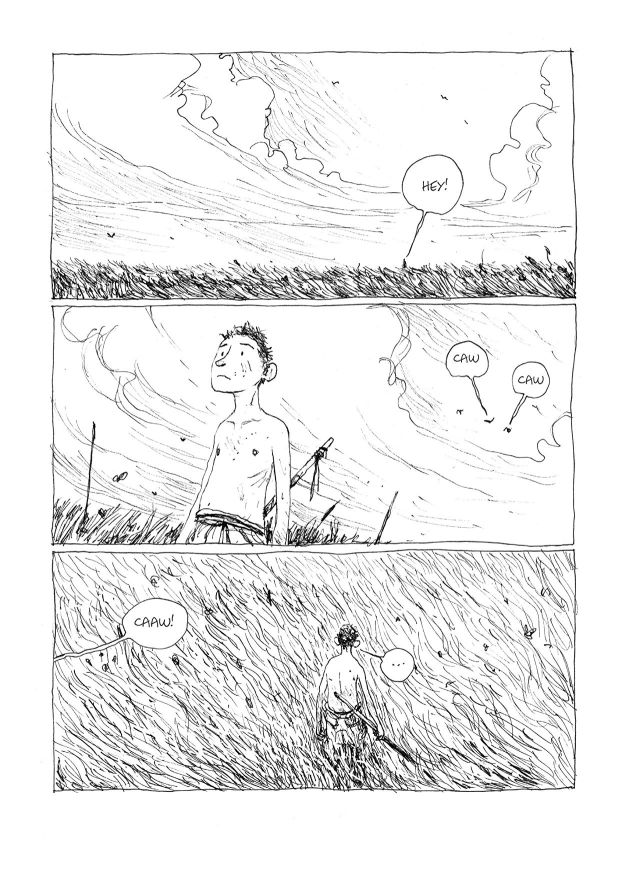

And yet, for all that, this isn’t an adventure story first and foremost, despite it having all the requisite trappings of one. Instead, Gipi — who illustrates the proceedings in a style awash with delirious contradictions best summed up as lush yet sketchy, expressive yet loose, detailed yet scratchy — opts to utilize well-worn tropes in service of examining things stemming from everything left unsaid between parents and their children, throwing into stark relief the ultimately fragile bonds that hold us together even after the one we’re bonded to is gone. What it means to be a father, a son, and even a man? These are the open questions he intuitively feels, rather than intricately plots, his way toward answering, and in the end, no firm conclusions are to be gleaned — all we can do, any of us, is try our best to figure out why we are the way we are, what we’re doing here, and where we’re going.

This task is made all the more difficult, of course, if we have no real idea of where we came from, and that’s no easy thing for our two protagonist brothers (whose names, curiously, we never even find out until nearly the end of the book) to even wrap their heads around, much less eventually come to terms with, but a kind of resignation to inevitability appears to be tentatively achieved by the time all is said and done — and while it’s just human nature to want to see characters we’ve come to invest something of ourselves in get what they want (or, in this case, feel they need), Gipi’s decision to opt instead to have them try to figure out a way forward without having realized their goal feels a lot less like a “cheat,” and much more like something truly, perhaps even achingly, authentic.

If narrative “payoffs” are important to you, then, Land Of The Sons may come up as short, as do the siblings themselves. But I think such a surface-level reading misses the point of what Gipi was aiming for all along: This is a story about losing your one chance to find out who you are, only to find the answer was within yourself the whole time.

Tags: Columns, Comic Books, Comics, Fantagraphics, Fantagraphics Books, Gipi, Italy, Jamie Richards, The Post-Apocalypse

No Comments