Cormac McCarthy wrote The Road.

Before that, he wrote the novel No Country For Old Men and before that, The Border Trilogy, among several more modern classics of sparse style.

Either due to the popularity and success of the Coen Brothers’ version of NO COUNTRY FOR OLD MEN or due to the popularity and success of the novel The Road itself, the book was a sure bet to be headed to the multiplexes as a cinematic adaptation.

(We’re not going to talk about his original script for THE COUNSELOR here, or the movie that resulted from it, only because I could do that all day if I started.)

Reading The Road, you get the sense fairly quickly that this is real literature, that forty years from now (if we’re still here), that kids will be reading this in English class, and that dumb kids like I was in high school English may not even realize that it’s a cool story, just because of the inescapable fact that their teachers are the ones making them read it. But it is cool, and so far beyond cool.

Even to this day, the best way to draw a guy like me in to read high-minded literature is to set it in a post-apocalyptic wasteland. That’s Cormac McCarthy’s masterstroke. The Road is genre enough for the freaks, and high art enough for the straights. It’s got a universality to it, more of an accessibility than some of his earlier works, which is an odd way to describe such a blunt, unsparing piece of business.

Here’s what it is: At the outset of the story, something abominable has happened to the America we know, coating it in wreckage and ash. We’re never told exactly what destroyed the country, though there are some sign posts.

In a way, the “what” doesn’t matter – the story is primarily about the relationship between a man and his young son, whose mother has been gone for years, who has been dead since not long after giving birth to him. The man keeps the pretense of hope going in order to help his son survive – the boy keeps hope going because he more genuinely has it. They walk a ravaged interstate highway, the titular road, in order to find warmth and food. Along the way, they have to evade the few fellow survivors of the apocalypse – mostly thieves, wretches, and cannibals.

And that’s mostly it. It’s a pretty simple story, but simplicity is deceptively difficult to accomplish in writing. It takes a true master to depict an entire world in few words. Just look at the first sentence, which sums up the entire story –

“When he woke in the woods in the dark and the cold of the night he’d reach out to touch the child sleeping beside him.”

Bang. That right away brings you into the story as it will come to unfold over the next couple hundred pages. It evokes the barren, stark loneliness and danger of the world that has become, and the tenderness and warmth represented by the still-at-least-a-little-bit-innocent son whose continued wellbeing the man must try so desperately to maintain.

McCarthy, as he generally does, writes here without quotation marks or contractions. The effect of this is immediacy. Once you get used to the unconventionality of the practice, it speeds your eyes along the page at a quicker rate than most writers are able to achieve. He’s directing your eyes. This is an important tactic in several scenes in particular, where certain horrific atrocities witnessed by the man and boy come up so quickly that they have the same blunt, visceral impact on the reader that it would have on the characters. And make no mistake, there are some hideous images in this book — i.e. a baby roasting on a spit, which is upsetting even to type here — though they are not at all included for exploitation or entertainment. They are of a piece with the author’s intent, of the honest portrayal of a chaotic, hopeless earth.

Also noticeable and telling in the writing style is the fact that character names don’t exist. The man and the boy are the man and the boy, not even capitalized, and are not, to my memory, described in much more detail than that. The other characters in the book might be more specifically physically described, but they aren’t given names either, which is honest – you wouldn’t learn a stranger’s name unless they trusted you enough to tell you.

In the case of our two protagonists, this decision on the part of McCarthy gives us an all-important sense of universality. Either subconsciously or overtly, male or female, old or young, we are led to envision a piece of ourselves or our loved ones in the roles. We picture our own fathers, our own sons, our brothers or grandfathers and so on. This, plus the childlike, innocent effect that writing without contractions might evoke, makes us feel warmly towards the two. It brings us right into caring about them and hoping that they are able to transcend their ordeal.

All that said now, I would have wondered about the point of filming something so intimate and lyrical and not all that plot-heavy. But if they were going to do it anyway, at least they made the right choice of director, in my opinion. The filmmaker who adapted THE ROAD, named John Hillcoat, is the same one who made THE PROPOSITION, the colonial-Australian-set Western released back in in 2005, which was written and scored by Nick Cave with all the properties and quirks of a classic Nick Cave song. In THE PROPOSITION, lawman Ray Winstone captures and forces outlaw Guy Pearce to hunt down an even worse outlaw, his brother, played by Danny Huston. It’s the simplest, most biblical of premises: Brother forced to hunt his own. And the movie contains all the tough-mindedness (and horror) which that set-up implies. THE PROPOSITION also carried some memorable visual poetry. That’s a friendly way of saying that, like the novel version of The Road, it wasn’t too big on plot or characterization either, but also like The Road, it clung to the ribs all the more for it. The movie is about the story, sure, but also it is entirely not about the story. It’s like a poem – a poem about violence.

I was also a huge fan of Hillcoat’s 2012 film LAWLESS, which I reviewed for this site at the time. LAWLESS, stemming from real-life events later collected in a book by the actual descendant of some of the characters portrayed, is by nature more plot-oriented and character-based than THE PROPOSITION, but it’s a hell of a good time, with a textured feel for period detail and some truly memorable performances from some great actors, one of whom being regular Hillcoat collaborator Guy Pearce (who last year headlined another post-apocalyptic yarn, David Michôd’s THE ROVER).

Though not everyone I know shares the same level of admiration about these movies, they all would probably concede that Hillcoat has a way with cinematic imagery, atmosphere, and the direction of gravelly, stubbly character actors. So personally, I came to John Hillcoat’s adaptation of THE ROAD. with great anticipation.

Anticipation was probably the wrong emotion to bring to the film, it turns out — not that this isn’t a production mounted with quality, professionalism, and feeling, but because it’s a shock to the system, like being doused with ice water.

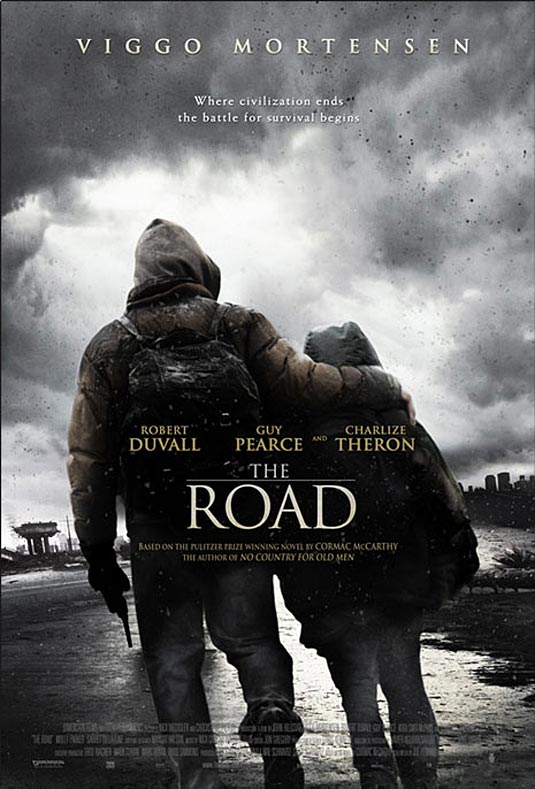

Viggo Mortensen plays the lead role of the man. An actor with a timeless profile, that Nordic-hero look that made him so perfect in THE LORD OF THE RINGS movies, he has the soul of a character actor, having been so interesting and unusual, from his early appearances in Tony Scott movies to CARLITO’S WAY to EASTERN PROMISES to A DANGEROUS METHOD and beyond. Here the physical and emotional commitment Viggo brought to his role was apparent, transformative and extraordinary. All of the heroic strength and vigor is chiseled away, leaving not much recognizable beyond the eyes and that distinctive, even peculiar voice, here rarely heard above a whisper. The character doesn’t have the energy for much more, and that’s eminently believable. If for nothing else, you must see this movie for Viggo Mortensen’s performance.

He’s also great with his young co-star, Kodi Smit-McPhee, who was affecting in LET ME IN, the as-good-as-it-possibly-could-be remake of LET THE RIGHT ONE IN, and who basically played the same role, a bit older, in last year’s post-apocalyptic primate drama DAWN OF THE PLANET OF THE APES. It’s rare to see a child actor who is neither precocious nor pretentious, who brings a tenderness and vulnerability to the film — the kid has a fragility, beyond the fact he’s a child. That’s effective but also limiting; Kodi Smit-McPhee has an unusual face, which makes him interesting on camera but makes him more of a distinctive presence. In other words, he’s not an every-kid. It’s a compliment everywhere else, and it is one here, but if there could be a criticism of the film THE ROAD at all, it’s that it lacks the universality I mentioned that the novel has. Mortensen and his young co-star are supremely excellent here but they cast a more distinct face onto a previously faceless work of art.

That’s not to play the same old refrain, “The book was better than the movie.” No, they’re different art forms. The book was different than the movie. Books do different things than movies do. Cormac McCarthy’s novel was brilliant, yes, and there are intimate, lyrical moments in the book that no movie can come close to capturing. But damned if director John Hillcoat (The Proposition) and his brilliant crew of production designers, cameramen, and costumers didn’t make something comparably special. THE ROAD as a movie is brutal and uncompromising and the only reason it didn’t hit me harder than it did is that it was so loyal to the book, incident-wise, that I knew what was coming in the end.

THE ROAD is a two-person show, and the rest of the cast is sparsely parceled out throughout the film’s running time. Frequent Hillcoat collaborator Guy Pearce, a man who knows how to maximize however much screen time he’s given, shows up in a small but pivotal role, as does the venerable Robert Duvall and the under-sung Molly Parker (Deadwood). Character actors Michael K. Williams and Garret Dillahunt make brief but indelible appearances also, but perhaps the briefest and most indelible performance comes from Charlize Theron, the biggest quote-unquote star who provides the faintest glimmer of light to a resolutely dark story. She isn’t around much, but where she is, she makes an impact upon the two lead characters and upon the audience, and where she isn’t, she makes an impact also.

That’s the heart of truth that THE ROAD gets at, that loved people affect the people who love them when they are present, and also when they aren’t. That’s as universal as truth gets. It’s a worthy statement for a story to make, no matter what medium the story arrives in.

— JON ABRAMS (@jonnyabomb).

- [THE BIG QUESTION] WHAT’S YOUR FAVORITE FEMALE ENSEMBLE IN MOVIES? - July 22, 2016

- [IN THEATERS NOW] THE BOY (2016) - January 24, 2016

- Cult Movie Mania Releases Lucio Fulci Limited Edition VHS Sets - January 5, 2016

Tags: Charlize Theron, Garret Dillahunt, Guy Pearce, John Hillcoat, Kodi Smit-McPhee, Literature, Michael K. Williams, Post-Apocalyptic Cinema, Post-Apocalyptic Films, robert duvall, Viggo Mortensen

No Comments