It’s a difficult thing to process, Nathan Cowdry’s Shiner — on the one hand it’s not a terribly complex narrative, despite the fact that’s it’s ridden with flashbacks, fever dreams, and less-than-reliable Ps OV. Really, I’m not kidding, the whole thing fits together in near-meticulous fashion even though by all rights it probably shouldn’t. But there’s so much simmering below the surface that it’s well-nigh impossible to determine how you feel about it even after two, three, or (in my case) four readings. Can I definitively state that I “like” this comic? I’m honestly not sure. I can, however, state without hesitation that I’ve found it impossible to get it out of my head, and that alone makes it worth talking about in some detail.

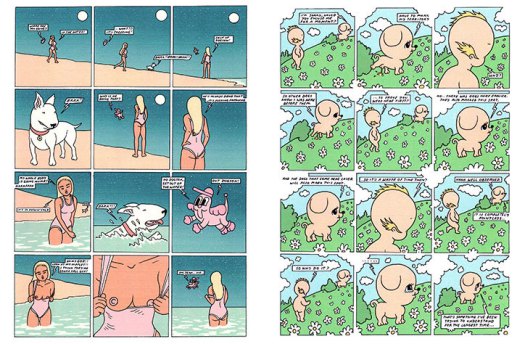

There’s something unsettling and potentially dangerous about Cowdry’s obsessions — like fellow Japan-obsessed Brit Trevor Brown, he blurs the lines between sex and violence, albeit in a far more borderline-genteel manner. Indeed, he skirts around the edges of various “forbidden fruits” without (crucial difference from Brown here) ever explicitly claiming any of them as his own — but he sure drops in plenty of knowing winks sufficient to clue even semi-attentive readers in. He’s got his tongue so firmly in his cheek that, who knows, it may all just be, as they say across the pond, one big “piss-take” — but it may not. And that’s equal parts intellectually and aesthetically stimulating — and frankly at least a bit worrying.

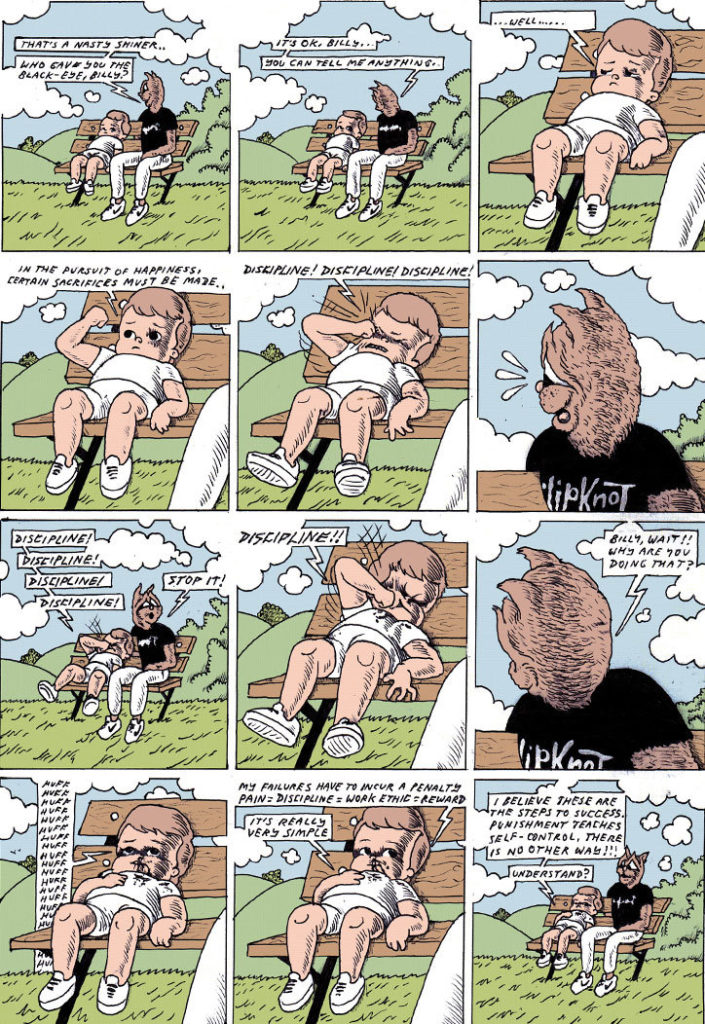

Our dual protagonists are Billy, an infant who looks more like a doll than an actual kid and seems to have a (fairly) fully-developed adult intelligence, and Kat, an anthropomorphic — well, you already know — in a Slipknot t-shirt who sees Billy punching himself over and over again in the eye (hence our title) and asks to sit with him, promising him that he’s “not a pedophile.” Which, thankfully, he’s not — but that doesn’t mean he’s well-adjusted by any stretch.

Cue the bizarre but compelling reminiscences that fill in the various “blanks” of each character, and take aim at any number of malignant presences floating about the contemporary cultural zeitgeist. Billy, for instance, confesses to being an internet “troll” who is afraid people might think he’s “alt-right” because, well, he sure sounds like he is, while Kat, for his part, dumped his last girlfriend when she became a 9/11 “truther” and wouldn’t stop haranguing him about Building 7 and the like. Sound like people you’ve encountered online? I’m betting it does.

Both characters are remarkably frank, especially for two “people” who have only just met, and here’s where Cowdry really pulls off a pretty remarkable feat : despite the fact that Kat’s obsessions flirt with being more overtly sexually violent, Billy comes off as the far more unlikable of the two, as he’s shown to have been — prior to his newfound penchant for self-abuse (and by that I do not mean masturbation) — hopelessly shallow at the best of times, downright narcissistic at the worst of time. And, like most “alt-right” assholes, he has a way of making himself out as the victim at all times. When he starts in about the love that he “lost,” for instance, Cowdry gleefully sets things up to make you believe the (very) young lady died, only to reveal that she became a he and Billy cut tail and ran — and has been lamenting his “loss” ever since.

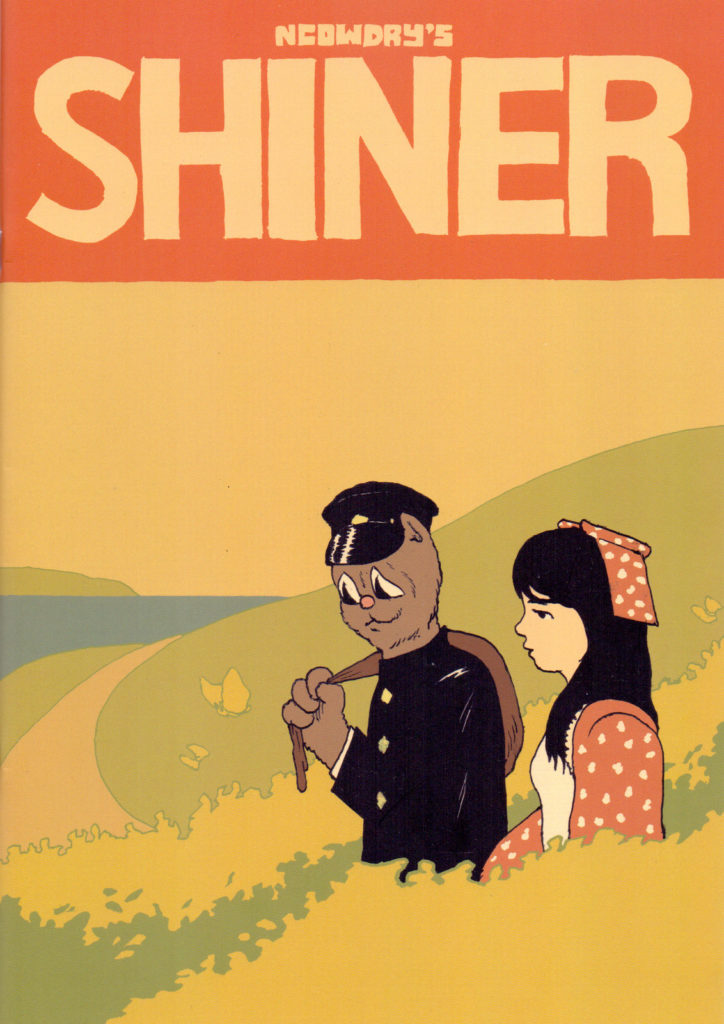

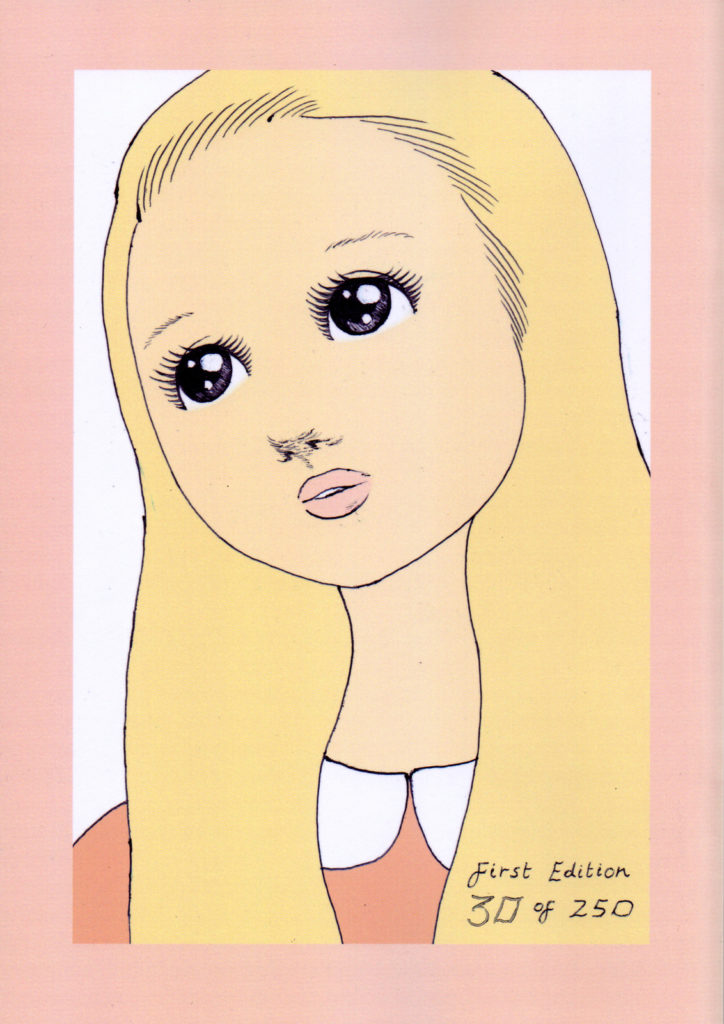

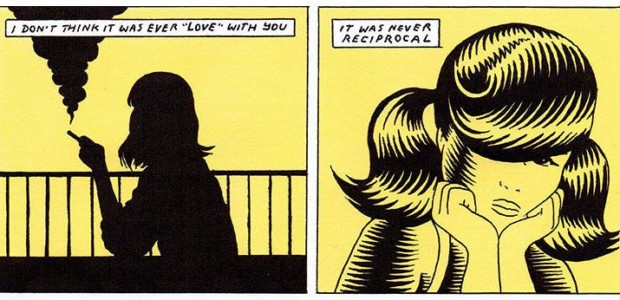

It’s not just Cowdry’s story that conveys a steady sense of unease, though — his overall visual aesthetic is one of innocence enshrined and corrupted simultaneously. Even someone as “manga illiterate” as I am can see the clear early-period shojo influence on display here, particularly in Cowdry’s female faces, and his lush and idealized pastoral physical settings (check out that cover!) literally scream that all is nowhere near as peaceful and idyllic as we hope it at least could be. This effect is compounded by his amazing use of 12-panel grids throughout — at first glance it seems rigid, formalized, but Cowdry’s utilization of clouds as a recurring visual motif has the effect of “bleeding” panels together and re-assembling the individual parts into a larger whole. There are pages that can literally be looked at as either a series of distinct images or a single, full-page illustration fragmented into single narrative/temporal moments. It all flows in a manner that can most accurately be described as “serene” (aided and abetted in no small part by Cowdry’s lush, borderline-pastel colors), but again — it feels transitory, fluid, at times even unsafe. There’s a definite brilliance at work here, but brilliance in service to what, exactly?

Comparisons to the films of Todd Solondz are probably not inappropriate here — the two seem equally fixated on mutability, nihilism, pre-teen sexuality, and the idea that “goodness” is a lie, for instance — and while Solondz’ work is also peppered with examinations of his Jewish faith while Cowdry takes time to espouse some rather conventional (but no less entirely sensible for that fact) arguments in favor of atheism, I feel like there’s a lot of “connective tissue” stringing Shiner together with films like HAPPINESS, PALINDROMES, and DARK HORSE.

And if you’ve followed along thus far, the last flick I name-dropped probably seems to stand out like a sore thumb given that it’s so remarkably different to anything else in the Solondz oeuvre — but I stand by its mention because, as was the case with that film, Cowdry does a rather stark 180 on Shiner‘s final pages and delivers a wistful and contemplative ending, replete with self-examination and regret that the first 90-plus percent of the book seemed downright incapable of, and rather than feeling the sense of whiplash you’d probably expect to, you realize that he’s been subtly, ingeniously, setting this up all along. That it took violence, misogyny, transphobia, and cultural appropriation to get to this moment of quiet (and sure to be wasted) revelation may be tragic, entirely appropriate, deeply cynical, or some/any combination thereof, but whatever the case may be, there’s no denying that it works.

And that could well be this comic’s nearest thing to a saving “grace” or “virtue.” It’s many things, and will no doubt elicit any number of disparate reactions from readers, none of which I would be willing to tarnish as being “wrong.” If you absolutely love it, I get it — and if you absolutely hate it, I get that, too. But there’s no arguing that Cowdry has created an almost singularly effective work here, one that is provocative, confrontational, and that instantly gains a foothold in your consciousness — whether you want it hanging around there or not.

******************************************************************************

While clearly not for all tastes, if challenging (or, as the case may be, forcing) yourself to contemplate decidedly uncomfortable realities of human nature and inter-personal (or, hell, inter-species) relationships is your bag, then the lavishly-presented (oversized, high-quality pages, heavy cardstock covers, full color throughout) Shiner can be ordered directly from cartoonist/publisher Nathan Cowdry at http://ncowdry.bigcartel.com/products

Tags: Comic Books, Comics, Nathan Cowdry

No Comments