Debut graphic novels are a tricky thing: publishers are going out on a limb by backing untested — and in most cases still-developing — talent, while said “talent” is often eager, perhaps even feels pressured, to make some kind of “statement” with their work in order to elevate it above its veritable army of competitors. Attention is a hard thing to come by in the crowded comics marketplace, and whatever you’ve gotta do to get it can almost be forgiven — at least on a logical, if not an artistic, level.

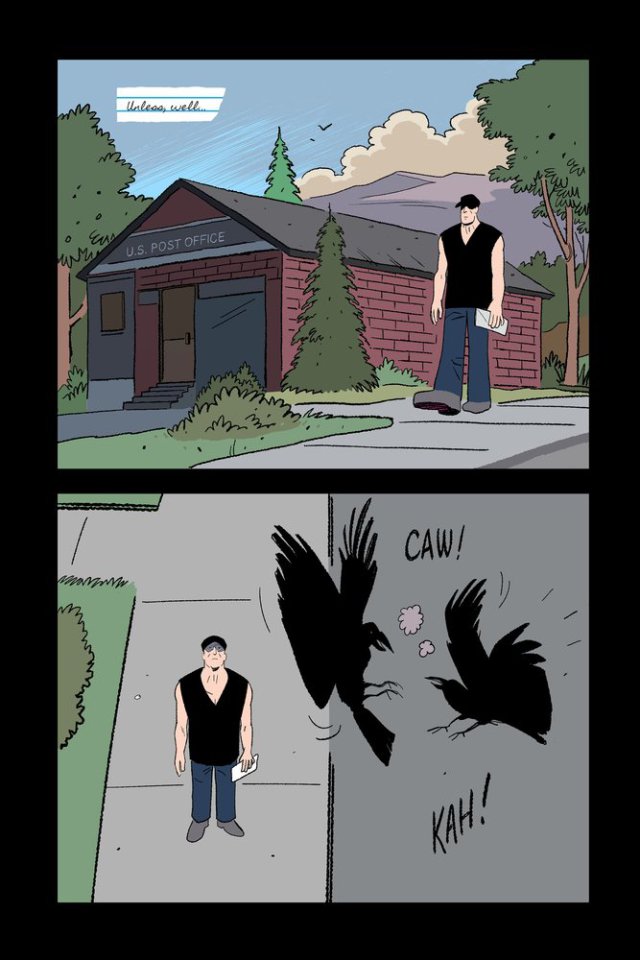

With all that in mind, then, cartoonist T.J. Kirsch is to be commended for eschewing the urge to make a big splash and instead telling a quiet, honest, heartfelt, and decidedly “non-flashy” story with his first book-length work, 2017’s NBM-published Pride Of The Decent Man. Clocking in at a lean 92 pages, a good many of which are of the single-panel “splash” variety, this is a book that tells a simple tale of hard luck and attempted redemption, that maintains a tight focus on its central character throughout, and that counts on clean, expressive illustration — extra points to Kirsch for his characters’ expertly-emoted (and deliberately, skillfully understated) facial and body language, as well as his deft placement of figures within space and their wistful movements through it — to do much of the heavy lifting given that said protagonist, Andy, is definitely what could generously be classified as a “man of few words.”

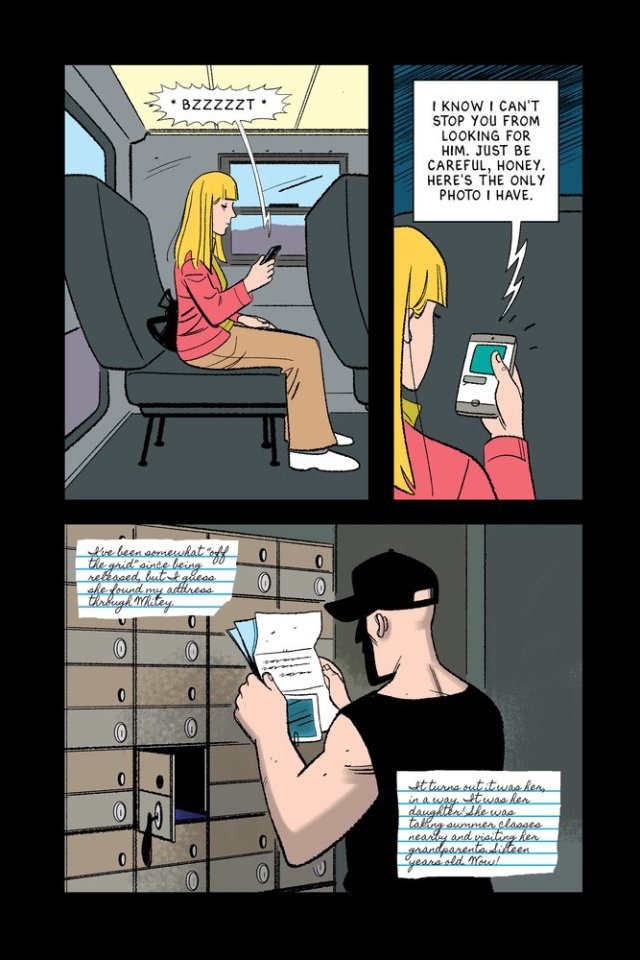

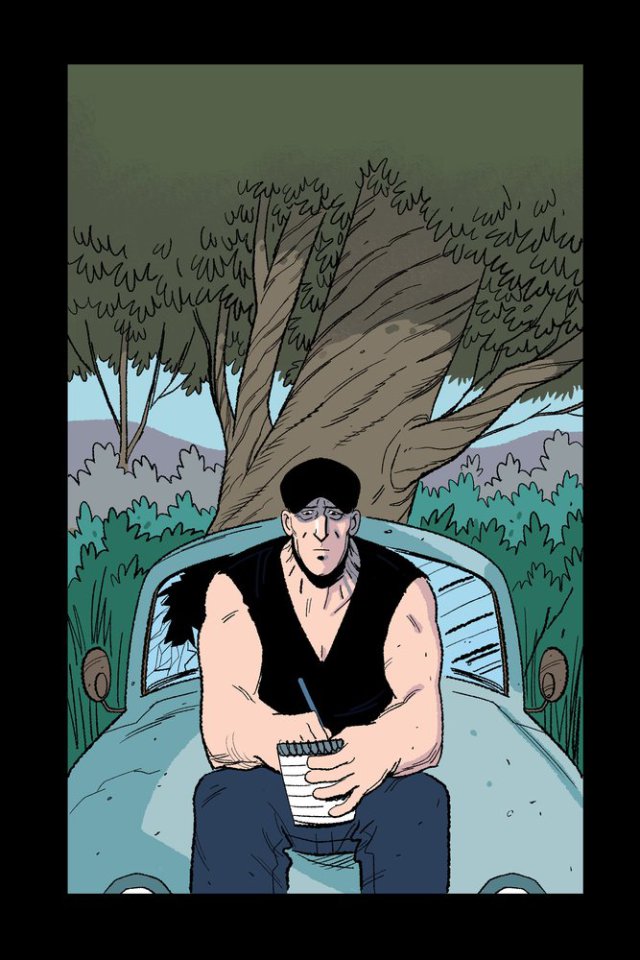

All of these are wise storytelling decisions on Kirsch’s part and establish a strong foundation for a work constructed with what, un-ironically, is also one of its primary narrative and philosophical concerns — integrity. There’s a lot of heart on display here, from the way Kirsch portrays the large, lumbering Andy as a man as physically out of step with his environment as his passive approach to decision-making (the episodic narrative sees him go from reluctant delinquent to even-more-reluctant criminal to ex-con) surely sets him apart from the socio-economic mainstream, to the way his journey to resolve his deep-seated alienation and strive for some sense of hard-earned inner peace is reflected in both his internal and external lives — the former being expressed by means of his journal writing, the latter in his tentative first steps toward establishing a relationship with the daughter he never knew he had. This is honest and earnest stuff, and mostly manages to avoid heavy-handedness — the key word there being “mostly.”

It’s no fault of Kirsch’s, but much of his narrative treads essentially the exact same thematic ground as Jeff Lemire’s concurrently-released Roughneck, but does so in a more austere, economic (and, I would argue, successful) fashion — but as is the case with Lemire’s book, Kirsch’s climactic final act yanks the rug he’s carefully placed beneath his feet right out from under them, but first consider how invested we become in our protagonist in fairly short order : in contrast to his “bad influence” best friend, Whitey, who could reasonably be seen as the source of all his woes, Andy never shirks his own responsibility for the messes he finds himself in, he lives with the consequences of his actions and never holds a grudge (against either Whitey, who gets off scot-free, or society), and he comes out the other end a thoroughly sympathetic character, a man of admirable simplicity and, as the title states, decency — a guy who deserves at least an honest resolution to his story, whether it’s a happy one or not.

Unfortunately, what he gets is the shaft.

Kirsch’s forced and contrived ending, seemingly pulled out of his as — errr, sorry, thin air — stands in such stark contrast to the naturalistic flow of the first 2/3 of his book that it’s downright whiplash-inducing. Andy is demoted from fully-realized, three-dimensional human being to mere chess piece in service to a pre-determined outcome. Unlike Rob Clough, a critic who’s probably more astute on his worst day than I am on my best, the tragic fate that Kirsch has cooked up for this guy we’ve come to admire and respect doesn’t bother me, but the way he gets there surely does: I won’t “spoil” anything in terms of specifics, but to say that it’s sudden and overly-choreographed and frankly not even all that believable is putting it mildly. Again, Lemire is just as guilty of this in his more-celebrated (chiefly because it was more publicized) book, but Kirsch handles it in much more clunky and awkward fashion. As a cartoonist, I believe he has a bright future; as a puppeteer — not so much.

Here’s the damn thing, though — and this should go some way, I hope, toward explaining why I just dropped that line about still being optimistic about Kirsch’s artistic career: just when I was ready to write this thing off as a loss (and a loss of $19.99 at that — “value for money” and “NBM,” once again, not residing in the same zip code), the last few, epilogue-esque pages very nearly redeem the mess made by the previous 10-15. The painfully cheap and ill-advised irony that sends Andy out the door, and that plays out as a veritable refutation of everything the bulk of the book had worked so hard to achieve, vanishes into the same ether it came from with just as little forewarning, and we are left with an entirely apropos, even quietly brave, finale that sees Andy’s daughter, at the very least, treated with the respect her old man deserved. Is it too little too late? I’m still in the process of deciding how I feel about that, but it at least leaves you closing the covers feeling generally good about most of what you’ve just read.

Final tally, then: 90% of Pride Of The Decent Man is so achingly, powerfully, and unassumingly human that it borders on the sublime, while only about 10% of it is anything less than magnificent. Unfortunately, that 10% is a lot less than magnificent, and it happens at the story’s most crucial point. I’ll be eager to see where Kirsch goes from here — and I have no doubt that this is a book that I’ll occasionally pick up and read through again. But there will always be a sense of “what could have been” associated with it, and hopefully we’ll look back at it as a tentative, flawed, but highly promising first work from a cartoonist who learned valuable lessons from it — both in terms of what he did right and what he did wrong — before going on to do truly great things.

Tags: Columns, Comic Books, Comics, T.J. Kirsch

No Comments