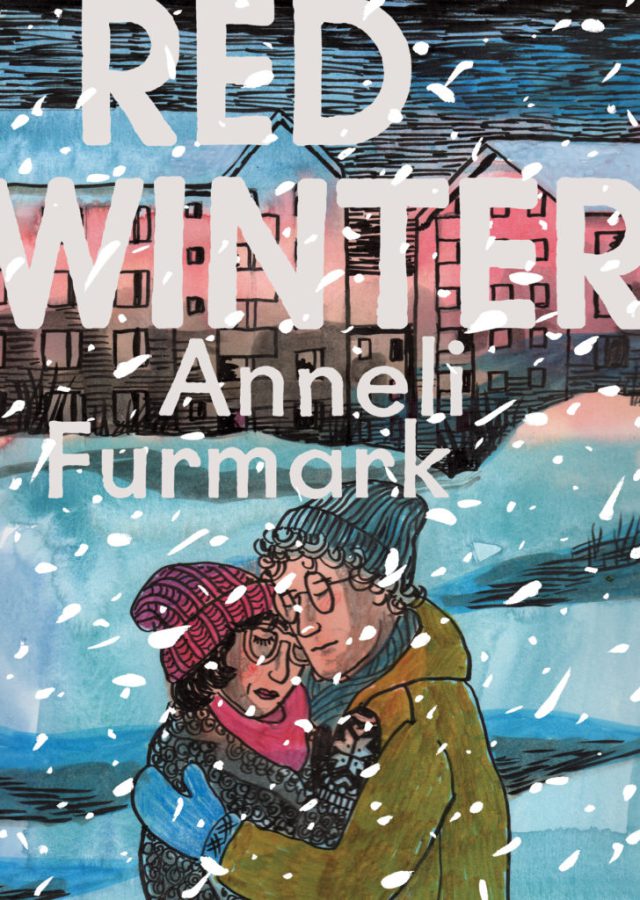

Like love itself, there is a poetry and beauty to Swedish cartoonist Anneli Furmark’s 2018 graphic novel Red Winter (the first of her works to be translated into English, courtesy of its North American publisher, Drawn+Quarterly) — but it’s often understated, unobtrusive, a “part of the scenery,” if you will, that necessarily informs all people, places, and things touched by it. Which isn’t to say that the particular parameters that necessarily “wall in” the love affair at the center of this story aren’t as electrified as the cliched “third rail” — they most certainly are, given one of the paramours is married — but, as with all things Scandinavian, even if and when the shit hits the fan, the consequences will, to one degree or another, be sublimated, put in something like their “proper” place, smoothed-over to fit into a new status quo.

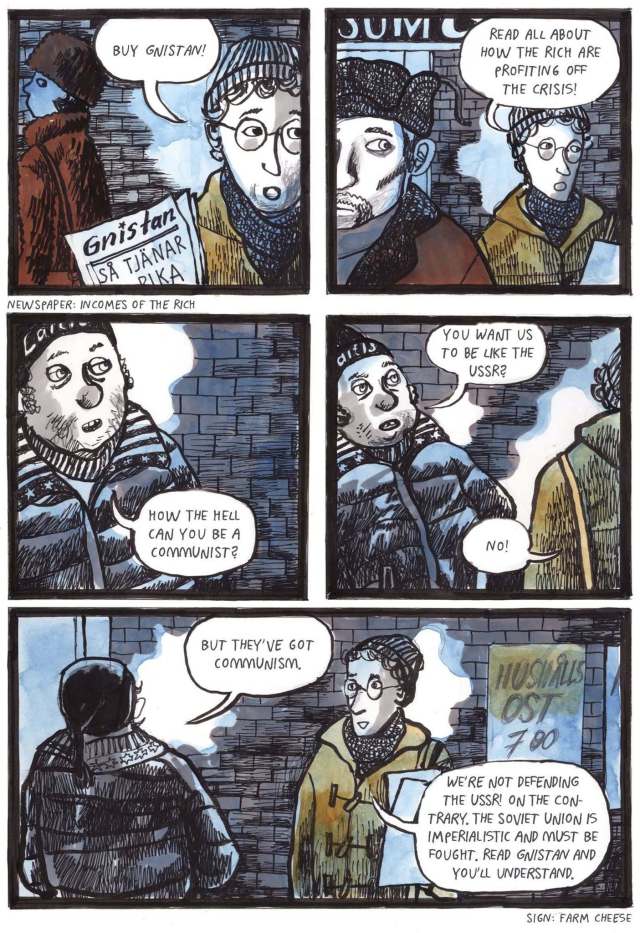

First, though, protagonists Ulrik (young, idealistic, Communist factory worker) and Siv (a mother of three 14 years his senior who works for/with the just-deposed Social Democrats) have to survive a politically and socially turbulent late-1970s Swedish winter in the isolated northern village that she’s lived in most (perhaps all, it’s never exactly clear) of her life, and which he’s just been effectively “deployed” to by his ostensible SKP (a Maoist political party) “superiors.” Who, then, fears discovery most — who perceives themselves as having the greatest amount to lose — is one of the richest veins of narrative tension that Furmark has at her disposal to mine.

Siv would be the most obvious choice, of course — she’s the one with the family, after all — but Ulrik’s comrades are fucking zealots of the sort that make even a Marxist-leaning individual like yours truly feel a little bit nervous. The structure of their organization is decidedly hierarchical, bordering on the downright tyrannical, and if you think a bunch of hard-liners who micro-manage their junior charges to the point of counting up how many party newspapers each manages to sell standing on street-corners on any given day are going to simply “go with the flow” if and when it’s discovered that one of said acolytes is involved with a rather milquetoast Socialist who doesn’t share their views and ideals, well — I’ve got a bridge to sell you. And it spans a frozen river in Sweden.

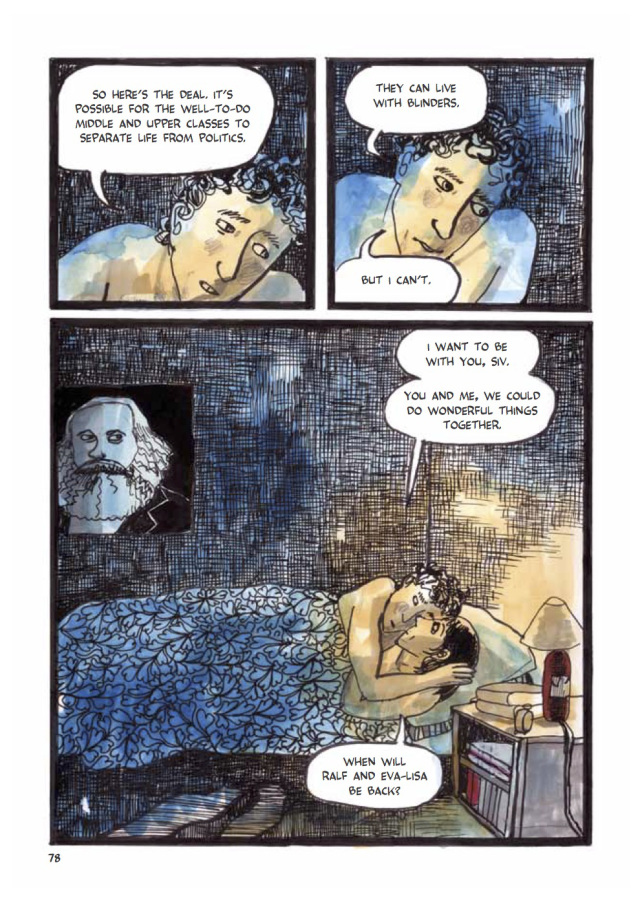

Told by means of a series of linearly-structured vignettes from the point of view of several individual characters (including Siv’s kids, which makes for some seriously interesting reading), for what is undoubtedly a love story first and foremost, Furmark’s book definitely has the thematic flavor of a thriller to it — but it’s a subtle one, a sympathetic one, a humanistic one. The affair is already well underway on page one — a wise choice that establishes the previously-mentioned pattern of things taken as a given right from the outset — and the passion the two have for each other is at obvious as it is unyielding, but the tensions limning it in are immediately present and accounted for, as well: ideology, responsibility, routine. The “tender traps,” as it were.

Furmark’s approach is remarkably frank and free of judgment, though, but not without passion — she simply doesn’t hit you over the head with a flood of manipulative scenarios designed to tug your heart strings in one direction or another. She has too much faith in the ability of her readers to figure all that out for themselves, it would seem, yet that doesn’t mean she isn’t keenly aware of the emotional power of every exchange from the warmest embrace to the most fleeting and furtive glance — or, for that matter, that she doesn’t understand, and communicate, the small little “soul death” that occurs when one lies to their partner; to their children.

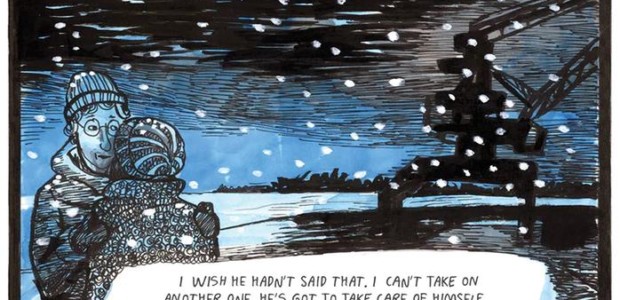

Is this, then, a doomed love? Logic would dictate that it absolutely must be — but since when does logic enter into the equation when it comes to affairs of the heart? Furmark’s lush, expressive, detailed cartooning — awash as it is in nigh-on lyrical, but never any less than appropriately dim and, dare I say it, “wintry” watercolors — has the look and feel of true passion to it, but more crucially of a passion as “under wraps” as most other strongly-held emotions in the icy Swedish hinterlands. To that end, then, perhaps just as great a threat to this love’s ability to endure comes from within as from without — forget the husband, the kids, the Maoist true believers, and ponder the question of whether or not Siv and Ulrik can find a way to make this thing work if they can’t even make sense of it themselves.

And since we’re tallying up a list of open questions, an equally big one you’ll have to puzzle out on your own is whether or not you, as a reader, think they should keep their affair going. Not whether or not you want them to, that’s another matter entirely — there’s definitely something real and true and even necessary that binds them together, but is this the sort of love story that will work best for both if it becomes a (sorry to be blunt, but) “full-time thing,” or would it be better for it to be a brief-but-passionate fling that they each remember fondly, even glowingly, for the rest of their lives? Because, let’s face it, we all need those, too.

After two readings of Red Winter, I admit to still having no firm answers as to how I feel about Siv and Ulrik’s situation beyond liking them both a whole lot and wanting the best for them, whatever that may be. Do they get that, in the end? It’s hard to say, and I don’t want to go down the “spoiler” road because this is a book you should feel your way through — as opposed to merely “read” — for yourself. I do know, however, that Furmark’s resolution, to the extent that she provides one, feels as true-to-form and authentic as all the events, large and small, that lead up to it, and that she has crafted an extraordinarily smart and heartfelt story that will no doubt endure as a personal favorite for many years to come.

Tags: Anneli Furmark, Columns, Comics, Drawn+Quarterly, Sweden

No Comments