The connective tissue linking music and memory is very strong indeed — most of us can remember fairly clearly where we were and/or what we were doing the first time we heard a favorite song; hearing one we haven’t heard in years often takes us right back to what was going on in our lives during the period when it was in heavy rotation; feelings attach themselves to songs permanently, inflexibly, the record in question causing at the very least faint echoes of the same particular mood or frame of mind again and again and again.

But there’s a lot more to it than “that song always cheers me up” or “oh my God, this one makes me think of (insert former lover’s name)!” Melody and memory are so inextricably entwined that Alzheimer’s and dementia patients often respond to songs from their younger years while words and even tactile sensations have no effect on them. The union of the two is so powerful, in fact, that it might even be argued to be primal in nature — so the idea that a cartoonist would tell the story of her or his life (or a part of it, at any rate) by means of musically-anchored reminiscences seems like a natural. And there’s probably no one better qualified to make such a conceit work than Summer Pierre.

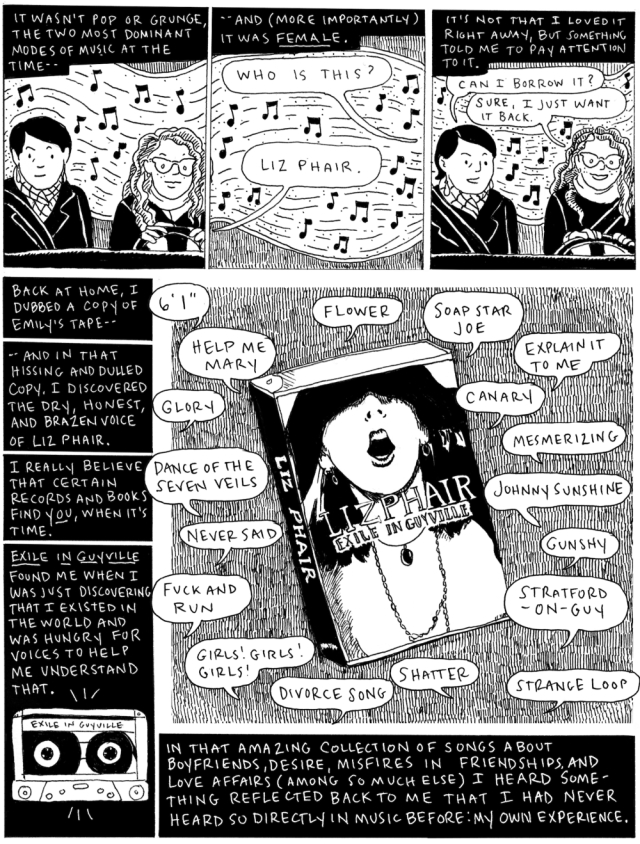

The auteur behind Paper Pencil Life hails from a musically-rich family background, and is no stranger to singing, songwriting, and guitar-playing herself, but her own personal musical journey isn’t precisely what her 2018 debut full-length graphic novel, the Retrofit/Big Planet-published All The Sad Songs, is about. Rather, it’s about how music has shaped her life on the one hand, how her life has shaped her shifting taste in, and relationship to, music on the other — and how the two have become symbiotic halves that make up the whole of her identity and existence.

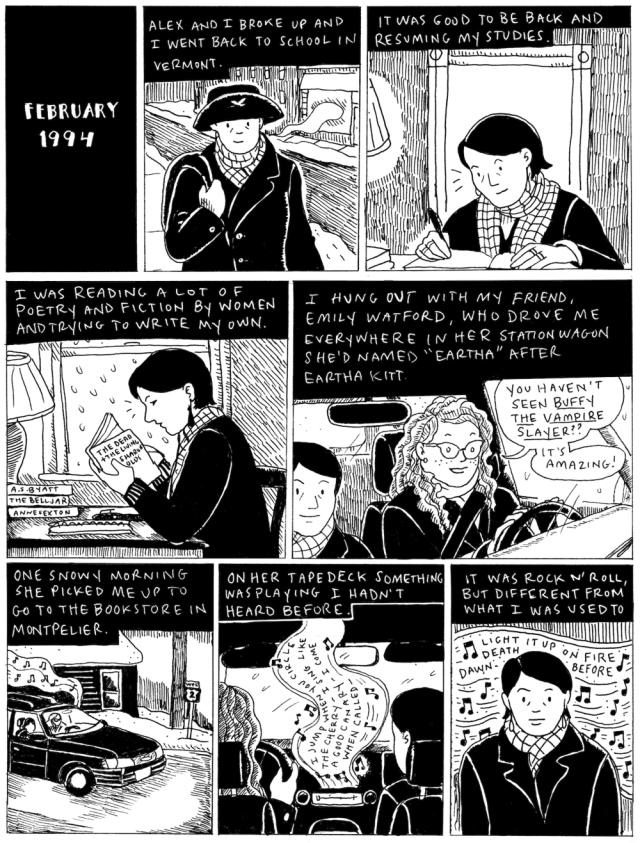

Put like that it probably sounds more grandiose than Pierre ever intended it to be, but this is truly an ambitious and innovative graphic memoir about her life in the early 1990s, a period that saw her move from California to Boston, follow her musical inclinations into the city’s open mic “scene,” and subsequently attempt to navigate her way through a series of interpersonal relationships that largely sprung from it. Nothing, perhaps, terribly ground-breaking on paper, but it is the method that is key here.

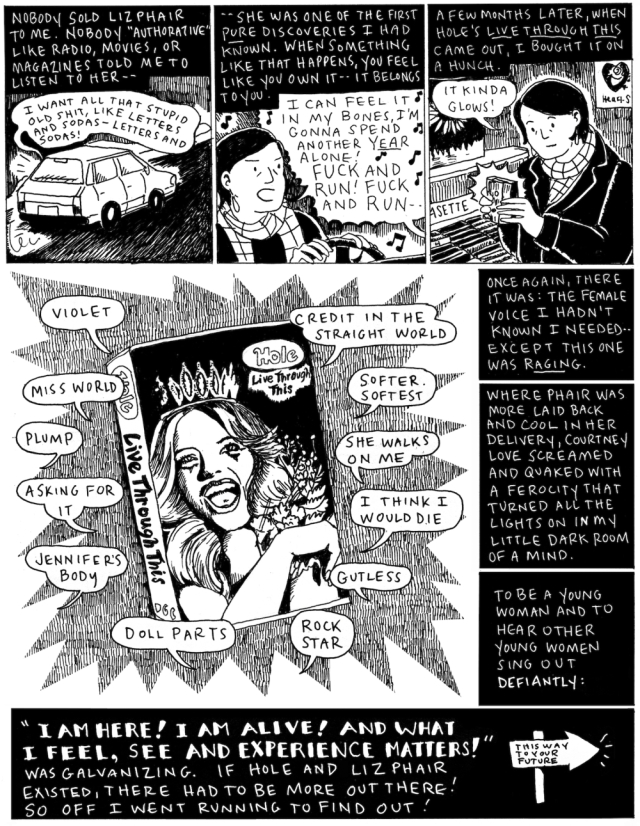

It’s not only her own music that informs these proceedings, you see, far from it : Pierre also affixes events in time in around albums that were contemporary with them and, even more interestingly, she extracts rich veins of memory from the mix tapes that she made for people she knew (for you youngsters out there this is how we used to do it in the days before slapping together a playlist for someone — it took hours, and was often a genuine labor of love) and the ones that they, in turn, made for her. She has many of these tapes to this day and literally remembers people through music, while also remembering songs in relation to the people who introduced them to her.

I made brief mention of the relationships Pierre forged while part of the Boston folk milieu, and much of this book’s dramatic tension stems from the fact that, it has to be said, not all of them were entirely healthy — and it’s one particularly tumultuous one that not only leaves her suffering from PTSD, but re-evaluating her relationship with music altogether, eventually setting her on an entirely different path of creative expression. There’s a wistful tone to this work on the whole, as one would expect given its subject matter and essential character, but this de facto “break-up” with something woven so deeply into the metaphorical “DNA” of her being — hell, of her soul, if you prefer such a term — borders on the harrowing, and whether or not she makes it through with a new, healthier perspective or ends up a shadow of her former self seems very much an open question for a time.

It’s probably not “spoiling” things to say that it all works out in the end, but it’s a difficult and painful period that’s communicated with admirable, even disarming, emotional honesty — and keep in mind this is a comic that places readers pretty deeply inside the cartoonist’s mind and heart more or less from the outset! So, yeah, like all lovers worth remembering, music puts Pierre through the wringer.

Her new medium of choice is sure proving to be an inspired one for her, though, it must be said — Pierre is one of those rare artists who uses every last millimeter of space in every panel to communicate information visually, her detailed cross-hatching, thick black shading, and precise rendition of minor details forming a highly emotive backdrop for her naturalistic figure drawings, and the candor and un-pretentiousness of her narrative tone is mirrored perfectly in the faces of her characters, each a truly singular individual with expressive reactions and mannerisms utterly unique unto them. Even the folks we meet briefly make an impression — go ahead, say it, just like a lot of songs.

I’ll be the first to admit that the fact I’m roughly the same age as Summer Pierre may go some way toward explaining why this book resonated so deeply, even indelibly, with me — I remember these times, I was young then myself, and there’s a character and ethos to the “slacker” or “Generation X” years that simply can’t be communicated with any sort of authenticity by someone who wasn’t a part of it. But you know what? None of the music Pierre was into was anything I could even remotely stand. I was heavy into black metal and post-industrial stuff back then, with a smattering of misanthropic “power electronics” on the side. I fucking hated “grunge” (except for Nirvana) as well as the popular acoustic singer-songwriters of the time — and I still do. Yet All The Sad Songs still knocked me for a loop, and not just for the overwhelming sense of nostalgia it engendered — nope, I was (and remain) in awe of the work of one of the very best cartoonists in the here and now, one who is fully arriving into her own and knows how to make every one of her pages sing.

Tags: Columns, Comic Books, Comics, Retrofit Comics, Summer Pierre

No Comments