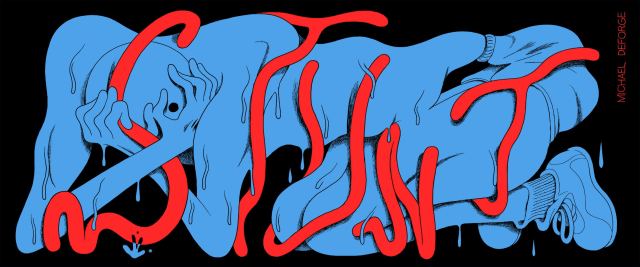

Annie Koyama’s “farewell tour” wouldn’t be complete without one more release from Michael DeForge before Koyama Press closes up shop, and while his latest, Stunt, may not qualify as a “book” so much as a stretched-out (in terms of its page count and physical dimensions) Chick tract, it’s certainly as thematically and conceptually dense as any of this one-time-ingenue cartoonist’s previous works, and further reinforces the almost giddily-obsessive nature of the psychosexual and physical terrors that are congealing and coagulating into something very much like a core “portfolio” of concerns at the heart of his overall artistic project.

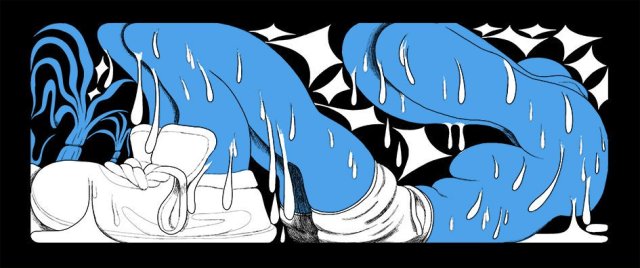

Roll call: Duality, the amorphous nature of identity, bondage and submission (both mental and physical), Cronenbergian body horror, fame and celebrity, overwhelming sexual need, personal apocalypse, and fluidity as the only constant.

Among other things, of course, but those are the big ones.

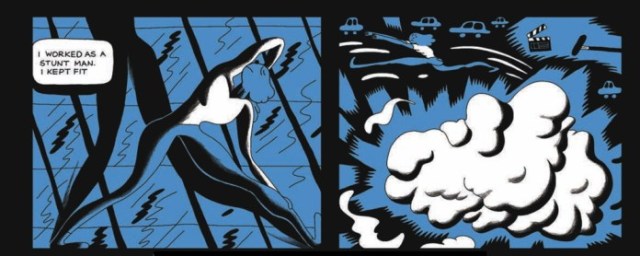

Rendered in blacks, whites, and blues that emphasize shape and motion while leaving stark identifiers such as features and faces deliberately ill-defined, as a study in art reflecting and consequently amplifying narrative, DeForge puts on a veritable fucking clinic with this brisk and disarmingly brusque read, our nameless stuntman protagonist voluntarily — hell, contractually — becoming the Hollywood star he doubles for gelling into reality before our unbelieving eyes with a kind of visual erudition that stands in stark contrast to, yet yins to the yang of, the disarmingly matter-of-fact scripting that disguises its sharp precision under a clever, and thin, membrane of sparse, clinical austerity. You know damn well there’s a lot going on in this comic — it never pretends otherwise — but it communicates its multi-faceted complexity in a manner that’s in no way taxing to your patience or perceptive faculties.

Peter Milligan and Duncan Fegredo’s criminally-underappreciated Enigma mined much of this same territory with a heavy dose of post-modern literary absurdism added to the mix, but DeForge’s shorthand take on it provides for a more immediate and visceral, if less “widescreen,” exploration of it all, although I may be dating myself with that reference — still, in for a penny, in for a pound, so let’s toss in this lyrical nugget that’s even older, but still sums up the proceedings here pretty nicely: “We walk and talk in time, I walk and talk in two — where does the end of me become the start of you?”

No, I’m not 50 yet, but it looms closer with every passing year, and with that in mind I have a kind of strangely intuitive understanding of why the movie star in this story wants to commit “career suicide” — chances to start over, to re-define one’s existence on one’s own terms, are all too rare, and his need to take that chance, paired with our ostensible “hero’s” need to assume the identity being left behind and take the “suicide” part of things more literally, is perhaps the most unique and painfully honest expression of the Cartesian principle you’re likely to come across in any medium.

Simple co-dependence is minor league stuff compared to the dynamic being limned herein, and indeed would almost present as a healthier alternative to the surrender of self that DeForge confronts us with, and about the only actual analogue I can draw is Genesis P. Orridge and Lady Jaye’s ultimately tragic, but at the same time desperately human, attempt to both transfigure and transform themselves into the same person, yet one that would also have been a product of their union — a third “life” that, theoretically, was to be both of their beings combined.

And yet even that is almost a more comfortable notion than the relationship portrayed in Stunt, given that Genesis and Lady Jaye, unconventional as their methodology was, still had continuation and survival, by means of a kind of de facto “procreation,” as their ultimate goal. DeForge offers no such concessions to the future, and presents us instead with need for its own sake — perhaps even “squared,” if you will, into the need to need. To fully subsume oneself into another, to end who you are, to sacrifice the entirety of your being and yet to still need to give up more? I wouldn’t call that love, that’s for damn sure — but I would call it the basis of perhaps the most challenging comic I’ve read this year.

Tags: Annie Koyama, Columns, Comic Books, Comics, Koyama Press, Michael DeForge

One Comment