While I consider myself a sentimentalist, and something of a romantic, one of my few concessions to a sense of machismo is that I’ve never been a fan of love stories. It’s not that I consider them too “feminine,” or think that watching them will somehow make me “girly.” I’ve just never quite clicked with them. That said, I’m not wholly averse to romantic films; I’ve just always had a weird sensibility about which ones I really engage with. With rare exception, I tend to gravitate towards — and really connect on a deep emotional level with — the ones where somebody dies at the end.

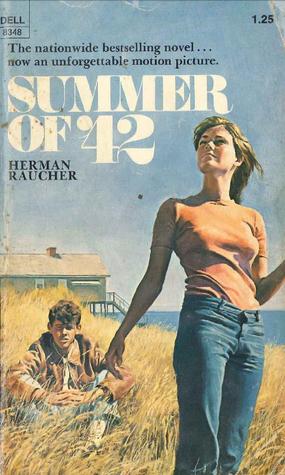

Now, I’m not some sort of sadist; I don’t get a thrill out of seeing two people fall in love and then watching one of them die horribly. I just find it strangely cathartic. My own early romantic relationships were pretty consistently defined by various traumas, so I suppose I see something of the lost possibility of my own youth in them; too, the movies I do tend to watch on the regular are either blood-soaked horror spectaculars or bleak tough-guy exploitation cinema, so tragic romances allow me to get in touch with my own inner softie without venturing too far afield. NOTTING HILL is sweet, sure, but, I’ll probably be watching SUMMER OF ’42 instead.

Looking back at the history of romantic cinema, it would seem I’m not alone in this peculiar fascination with love and death — how else to explain the career of Nicholas Sparks? In honor of our cultural fixation on the courtship of Eros and Thanatos (thanks for that one, Pennie), I’d like to take a look today at some of Hollywood’s great doomed romances.

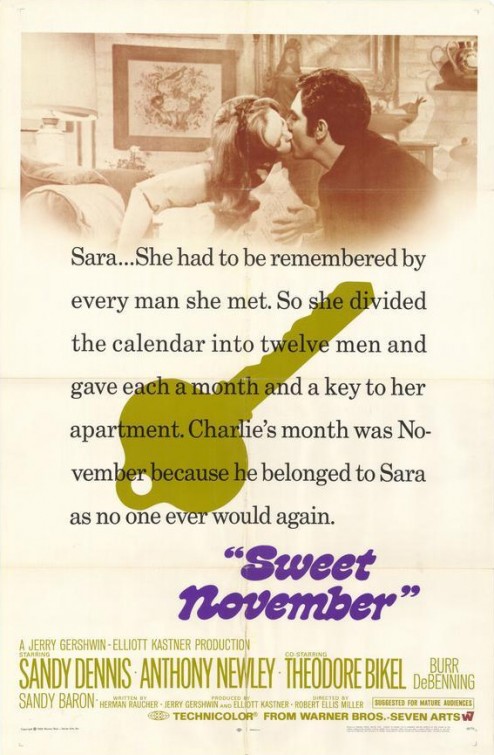

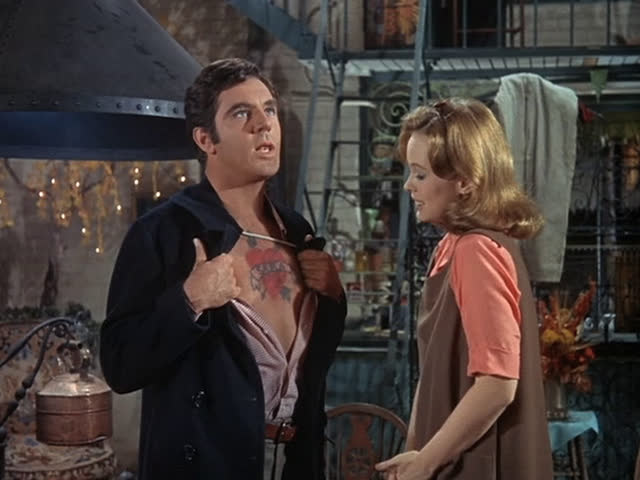

SWEET NOVEMBER (1968)

THE COUPLE: Boho chick Sarah Deever (Sandy Dennis) and insufferable posh bastard Charlie Blake (Anthony Newley)

WHICH ONE DIES: She does

I’ve written about SWEET NOVEMBER at length before, so I won’t run through the gamut again, but no list of post-war tragic romances is complete without it. While it may not have been the box office phenomenon its progeny would prove to be, it was a quiet cult hit that especially took off with the Vietnam generation. I’ve found several reminisces online either from veterans or the wives/ex-girlfriends/widows of veterans recalling going to see this before they were deployed, leading me to believe that going to see SWEET NOVEMBER before getting shipped off was a brief but powerful tradition. That the film’s template would be repeated for decades also leads me to believe that, although they may not have known it, this was the movie that influenced the course of romantic dramas for generations. Sarah is the proto-manic pixie dream girl, an eccentric, free-wheeling bohemian who lives in a wacky loft apartment with wacky neighbors. Charlie is the proto-male lead in any given romantic drama, a tightly-wound, terminally uptight, emotionally constipated dude who needs to learn how to let loose and just love, man. Their story is the proto-romantic drama: Sarah succeeds in her quest to teach Charlie how to enjoy love, but in the process discovers herself learning a few things, as well — too bad she’s got a terminal illness and will drop dead any day now. Most subsequent movies of this stripe don’t end with the guy happily walking away so the girl can hook up with some random dude, but the broad strokes of the story undoubtedly laid the groundwork for dozens of films to come.

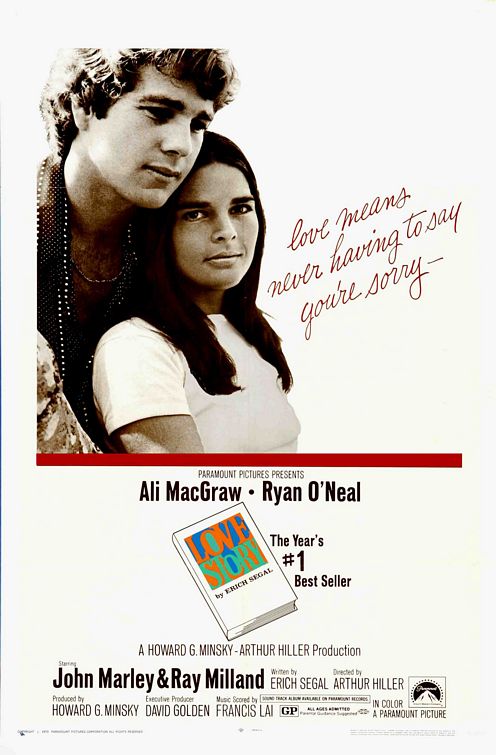

LOVE STORY (1970)

THE COUPLE: Boho chick Jenny Cavalleri (Ali MacGraw) and insufferable preppie bastard Oliver Barrett IV (Ryan O’Neal)

WHICH ONE DIES: She does

Though SWEET NOVEMBER may have laid the foundation for our popular post-Vietnam conception of tragic cinematic romances, LOVE STORY is the movie that built a grand and glorious temple on top of it. In many ways, it’s essentially SWEET NOVEMBER but with coeds and WASPier protagonists (Ryan O’Neal somehow manages the feat of coming off whiter than Anthony Newley, who was born in England). Were it not for the fact that author Erich Segal —formerly a college professor — loosely based the leads on a pair of his former students, audiences familiar with both films could be forgiven for assuming that this was a cash-in. Again, we’ve got a boho-girl lead in the form of Ali MacGraw’s Jenny, a quick-witted, foul-mouthed, sarcastic-but-sweet working-class girl who preaches atheism but refuses to take off the cross that her mother gifted to her before passing away. Again, our male protagonist is an upper-crust, up-tight, up-his-own-ass guy, this time a preppie grad student named Oliver. Again, they fall in love and teach one another things about life; and, again, she buys it from an unnamed terminal illness that’s probably cancer. Apparently, love means never having to say you’re sorry and a tragic romantic drama means never saying what your heroine is dying from. While SWEET NOVEMBER was a cult success, this one was just plain a success. Like many subsequent films to follow, LOVE STORY was a critical whipping post but a cultural touchstone. While Harlan Ellison called it “shit,” Newsweek called it “contrived,” and Judith Christ called it “Camille with bullshit,” audiences flocked to it in such droves that, adjusted for inflation, it’s still one of the highest grossing movies in history. (Notably, the only popular figures comfortable with voicing their love for the movie were Roger Ebert and, improbably, Richard Nixon; take from that what you will). This is the movie that Nicholas Sparks will forever be indebted to.

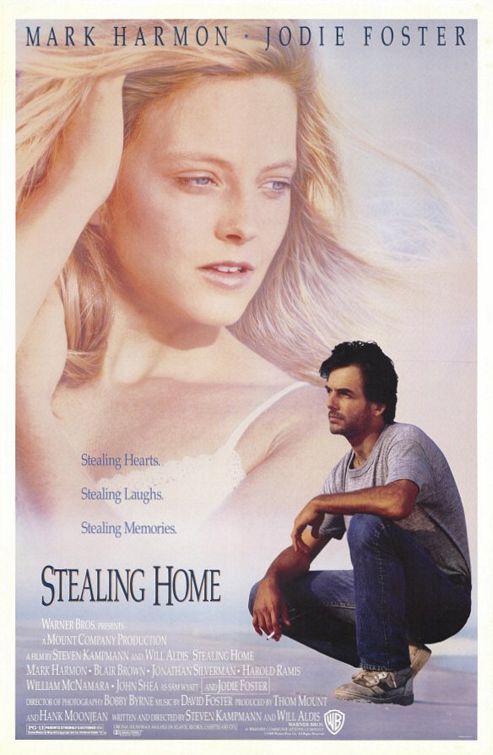

STEALING HOME (1988)

THE COUPLE: Free spirited older-girl Katie Chandler (Jodie Foster) and baseball-playing everyman Billy Wyatt (William McNamara)

WHICH ONE DIES: She does

I’ve got complicated feelings about this one. For much of its running time, STEALING HOME is as bland a coming-of-age movie as you could ask for: In the 1980s, washed-up baseball player Bill Wyatt looks back on his childhood in the 1960s, leading us into a series of AMERICAN GRAFFITTI-esque stock-episodes culled from every Boomer nostalgia movie ever made, including hanging out with his buddies, playing ball, and losing his virginity in a ludicrously complex set piece that comes off like an unfunny porn parody of Three’s Company. It’s the parts that focus on Billy’s relationship with older girl Katie Chandler that set the movie apart, though, and make it worth a second look. While this is, ostensibly, a love story, the relationship between the two begins — and largely remains — a friendship, with Katie mentoring Billy through the tumultuous waters of adolescence and acting as a pillar for his mother when her husband dies in a car accident. The hint of romance only emerges briefly as Katie prepares to leave town for good, and the pair’s one-night-stand doesn’t come across so much as the sexual fulfillment of a long-burning attraction but as more of a physical and spiritual affirmation of their agape love (though that subtext is sharply undercut by the use of what’s possibly the worst ’80s pop song in the history of cinema; people who wanna shit on “We Built this City” ain’t never heard “And When She Danced (Love Theme from Stealing Home)”). Where the movie most succeeds, though, is in looking at the potential dark side of the manic pixie archetype: Katie is free spirited and headstrong, but she also makes some really bad decisions (like encouraging Billy’s mom to get drunk and hook up with a stranger a few days after the funeral) and, as the movie progresses, we begin to realize that a lot of her bravado is covering up deeply seated insecurities and probably undiagnosed clinical depression. When the film finally returns to the ’80s for its last act — a tour de force of “lost American” storytelling that could be an Arthur Miller one-act — we get the jarring revelation that Katie committed suicide after two decades of abusive relationships, drug addiction, and disappointment. Indeed, the real spiritual and narrative meat of the movie emerges in the final third, as Bill learns that Katie entrusted him with disposing of her ashes in her will, figuring that he was the only person left on earth who really cared for her. It’s the sort of grownup assessment of middle age, loss, and compromise that movies usually eschew for cheap platitudes about starting over and coming to terms with the past. The culmination of the movie, in which the adult Bill attempts to perform some task to properly honor Katie’s memory, is beautiful in its conception if not its execution — if there’s a movie on this list worthy of a remake, it’s HOME.

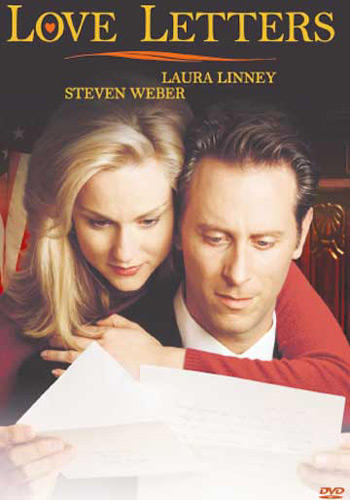

LOVE LETTERS (1999)

THE COUPLE: Ambitious career-preppie Andrew Makepeace Ladd III (Steven Weber) and plucky hot-mess Melissa Gardner (Laura Linney)

WHICH ONE DIES: Take a wild guess

The only entry on this list to have serious literary credentials (its source play won the Pulitzer for drama), LOVE LETTERS is an interesting culmination of the previous’ thirty-years worth of romantic dramas in that it borrows so much from what’s come before it while doing something entirely new. Like LOVE STORY, our male protagonist is a privileged, elaborately named preppie, although in the hands of Steven Weber, Andrew is a much more relatable, human, and all around nicer than Oliver. Melissa, meanwhile, is the spiritual successor to STEALING HOME’s Katie Chandler — a happy-go-lucky, imaginative and free-spirited young woman whose vivaciousness is partially a cover for deep-seated unhappiness and undiagnosed mental illness. Uniquely, the pair almost never interact face-to-face. The title comes from the pair’s relationship developing exclusively through the correspondence they share over the years, beginning with a thank-you note after a birthday party that turns into pen-pal letters from separate prep schools, postcards from Summer camp, and eventually professions of love as Andrew becomes a successful attorney (and later Senator) and Melissa endures a loveless marriage, alcoholism, and worsening depression. Though the pair finally meet for a full-blown affair when they’re both well into their thirties, Andrew’s public life and Melissa’s crumbling life mean the clock is already ticking down to tragedy, and the last scene finds Andrew penning a condolence letter to Melissa’s family following her suicide. The quiet, final lines of the movie — “Thank you,” spoken by Andrew’s imaginary manifestation of Melissa — are subtly moving in a way that more elaborate speeches and professions in other movies of this ilk can only hope for, and finally give a well deserved, heretofore unknown dignity to all those dead bohemian women.

Tags: Ali MacGraw, Anthony Newley, Arthur Hiller, Emily Hampshire, Erich Segal, Harlan Ellison, harold ramis, Helen Hunt, Jennifer O'Neill, Jodie Foster, John Marley, Laura Linney, Love, Mark Harmon, Ray Milland, Richard Jenkins, Richard Nixon, Romance, Ryan O’Neal, Sandy Baron, Sandy Dennis, Stanley Donen, Steven Weber, Theodore Bikel, tommy lee jones, William McNamara

No Comments