Every good film is a miracle.

That may not be the single best word for the extreme unlikelihood of the end result, and it may be a generous way to look at it, but still. Think about it: A good film starts with an idea. One person has it, then that person shares the idea with more people. The idea becomes a screenplay. The screenplay is the movie’s foundation. It has to be strong for the movie to be any good. Anyone who’s ever put pen to paper or finger to keyboard knows full well that good isn’t easy.

Then the people with the script have to go convince the people with the money to fund the enterprise. If that works, a whole crew of craftspeople are hired. For the finished movie to have a chance of being good, all of these people – directors, set designers, cinematographers, costumers, prop masters, sound recordists, stuntpeople, armorers, drivers, actors, production assistants – all of them, all of them, all of them have to be doing their jobs well. Think of all the factors that can get in the way: The money runs out, the human element leads to friction, the weather gets rough, life, death, nature itself. Just making a movie is an ordeal, a beat-the-clock endeavor.

Then, once it’s in the can, a million more things can go wrong during the post-production process. With or without cynicism, this is the truth: The odds are against a good movie making it through. A good movie is a miraculous quantity. Maybe it’s a small miracle, like a spider walking upside down on a ceiling, or a sparrow in flight.

A good film is a miracle. A great film is a larger one. It’s a matter of scale. Having only seen it a handful of times so far, and not wanting to damn it down with expectations no popular entertainment can bear, I’m not yet calling MAD MAX: FURY ROAD a quote-unquote great film, or an instant classic, or yeah “a miracle,” but I’m getting there.

If you love movies, you believe in miracles, or you want to. That’s why you keep going back for more. One person had an idea a long time ago, and a lot more people put in a lot of hard work to get that idea to your eyeballs and your earholes and your brain. On those terms it’s sort of awesome, in the linguistic sense of the word.

It takes an audience two hours to watch a movie, and it takes a critic probably some time more than that to compose a thoughtful review, but it takes a platoon of filmmakers of all trades, living with the movie for months or years, to make the thing a reality, and the more one keeps that in mind, the more literally amazing an achievement it becomes.

MAD MAX: FURY ROAD, written by Brendan McCarthy, Nick Lathouris, and George Miller and directed by George Miller, is at the very least a very good movie. Sometimes these things are objective. I’ll argue it’s a great deal better than just “very good,” but that’s where subjectivity comes in. You want to haggle over letter grades or stars, we can do that. But this is superlative work by any measure or standard.

MAD MAX: FURY ROAD can be looked at as a self-contained story on its own, and in that light it is an efficient, inspired triumph of craft and storytelling. In context, as the fourth film featuring the adventures of the character of “Mad Max” Rockatansky, it’s a fair deal more impressive.

As a filmmaker, George Miller exploded onto the international stage with 1979’s MAD MAX, a brisk, nasty tale that introduced future movie star Mel Gibson as the title character, a highway cop in a lawless, post-apocalyptic Australia who turns to revenge when a band of criminals run down his wife and child. “Mad Max” is both mad in the sense of being made very very angry, and mad in the sense of being driven insane by grief and anger. The film is far more of a thrilling and visceral exploitation film and a stunt showcase than a character piece, but the character’s very literal madness has distinguished him from the very start. For the good and more recently for the bad, Mel Gibson was great in the role. His best films have always made good use of his rare talent for projecting torment, viciousness, and anguish onscreen, and his three films with George Miller are certainly among his very best films.

THE ROAD WARRIOR came next, in 1981. Larger in scale than its predecessor, but comparatively simple and direct amongst the company of the great action films, THE ROAD WARRIOR is a masterpiece of momentum and mounting tension. This movie alone proved that George Miller is one of the greatest action directors in the world. There aren’t many who can build an action scene with such clarity and efficiency, and of the few who can compare, even fewer are willing to really go for broke with the abject weirdness. THE ROAD WARRIOR has characters like The Feral Kid, a little Eddie Munster of the wasteland, and Lord Humungus, a bodybuilder in a hockey mask who might recall Jason Voorhees with a better vocabulary. And there again is Max Rockatansky, and his dog, and the dog is just about the last sign of any empathy in Max. This is where the ethos of the character becomes even clearer; the events of MAD MAX and whatever horrors in between have made Max just this side of a total misanthrope. Most people slow down to rubberneck at a car accident – Max has seen so many he doesn’t even consider pumping the brake.

In THE ROAD WARRIOR and in the next two installments of the series, Max is called upon to help various nomadic societies on the fringe of a hostile post-apocalyptic hell. The key to Max is that helping strangers is the last thing he wants to do. Many wannabe tough-guy movies play at nihilism but outside of Clint Eastwood in THE OUTLAW JOSEY WALES, you won’t find a less sentimental protagonist, and Josey Wales was clingy by contrast. Max Rockatansky has been so traumatized by the world that he can’t afford to care. That George Miller and company manage to indicate the subtle internal shift in THE ROAD WARRIOR, to edge Max towards the decision to aid the ones who could use a hand, is what gives it the power it has, beyond the fierce action scenes – but the fact that the same note is played again in MAD MAX BEYOND THUNDERDOME and again in MAD MAX: FURY ROAD is truly impressive. Time and again Max doubles back on his resolve to forge ahead alone, and four times now he’s set off into the desert on the solo by movie’s end, but the marvel of these movies is that it feels right and new every time.

Then again, MAD MAX: FURY ROAD really is something new. It arrived here in America nearly thirty years to the day after MAD MAX BEYOND THUNDERDOME did in 1985. The most obvious difference is that Tom Hardy has replaced Mel Gibson in the role of Max.

Mel Gibson and the character of Max Rockatansky grew far apart in the span of thirty years. For better or worse, we collectively know more about Mel Gibson now than any of us likely want to. A lot of us have gotten drunk and said things we regret. Fewer of us, hopefully, have ever said to a woman, “Shut the fuck up! You should just fucking smile, and blow me! ‘Cause I deserve it!” Unless Max Rockatansky, a man who loved his lost wife and grew to grudgingly respect the magisterial Auntie Entity, somehow became warped enough in intervening years to transform into a virulent misogynist, Mel Gibson was no longer good casting for that role. There is, however, another role in FURY ROAD he could have played. But for Max, George Miller needed to recast.

Tom Hardy was an intriguing choice. Always compelling to watch, Hardy appears happiest in demented character roles which either distort or disfigure his appearance. He can play madness, as he did in BRONSON, but not in the traditionally heroic way the role of Max requires. When Tom Hardy plays madness, he goes all the way. (Max is an unusual hero, but still a heroic archetype.) When Tom Hardy plays a more traditional hero, his characters are notaby taciturn – see him in LAWLESS or THE DROP for examples of what I mean. Those characters are quiet men with a great capacity for physical violence, and that’s more in line with what he accomplishes here. It’s the right choice, but we’ll get more into that in a minute.

The title card for the movie reads “Tom Hardy as Max Rockatansky” and “Charlize Theron as Imperator Furiosa.” His name is higher up, but her name actually comes first, unless you’re Japanese or Hebrew and you read right to left. That’s the first cue you get: This is her movie.

Something I thought about on my fourth or fifth way through the movie is how the modern moviegoing experience affects the initial viewing of the film, by which I mean by the time most of us come to see FURY ROAD for the first go-round, not only do we have a solid idea of who Max Rockatansky is, having seen or at least heard about the previous films, but we also probably know a fair amount about Imperator Furiosa. Cinemaniacs like you or I have devoured every piece of press and reportage about this movie, thrilled to know it’s on the way, and we’ve seen and read interviews of Charlize Theron and Tom Hardy describing Furiosa, in general terms at least. Even laypeople have seen trailers. We know she’s somebody who Max meets along the way and who he maybe scraps with before she becomes an ally. But imagine you came to this movie totally cold! “Imperator Furiosa” would be a fantastic name for a female archvillain. Could she be a successor to Auntie Entity, running an all-new Thunderdome? Without a doubt, Charlize Theron could have just as easily been the main antagonist of FURY ROAD, and we the audience would have had to worry for Max, since by 2015 Charlize Theron was already firmly established as a redoubtable screen presence, and objectively a bigger star at that point than Tom Hardy.

I remember the first time I saw Charlize Theron on screen. It was in a trailer for a movie called 2 DAYS IN THE VALLEY, where she plays a femme fatale. The movie was sold heavily on her physical beauty. It was her first major role and she was only 21. Many stars are stars right out of the gate. After that movie, she appeared in smaller roles in THAT THING YOU DO! and TRIAL AND ERROR, two movies I saw upon release. She registered, but it was in her next movie, THE DEVIL’S ADVOCATE, in 1997, just a year after her debut, where it became clear that her looks, which trailers and magazines fixated on, were only bait, and here was an actor of devastating emotional precision. That’s the switch. Keanu Reeves was the nominal star of that movie, and Al Pacino gave a historically campy performance, but Charlize Theron is the actor to remember there. This is five or six years before MONSTER, the one that demanded everyone else notice the force of her. That movie was directed by Patty Jenkins, who since proved decisively that she knows how to present a woman as a worldwide action star. Also note how Charlize Theron worked with another female director, Karyn Kusama, on AEON FLUX, her first action film as the sole star. I’m going to argue that Charlize Theron remains undervalued for her contributions to action cinema and to pushing it forward towards the future (even though as a straight white man, that argument is one I’d relinquish to female writers who can surely make it better). ATOMIC BLONDE and THE FATE OF THE FURIOUS, whether or not one loves those movies, are important steps further in this progression.

By the time of FURY ROAD, Charlize Theron had been in movies for almost two decades and had rocketed past weightless ingenue roles to demand better. She hadn’t always had roles and films to suit her talent, but she had the gravity of a star and the canniness to subvert the expectations that still somehow kept being thrown at her for looking the way she does. In retrospect, George Miller would prove to be the perfect collaborator, though it might not have been so obvious at the time to observers and though according to this recent oral history at the New York Times, it wasn’t always an easy job for either of them.

To backtrack a moment, but to illustrate the brilliant crafting of this movie, the first character we see is Max. Specifically, Max has stopped his Pursuit Special just long enough to get out and urinate into the open desert. Not for nothing, though almost surely coincidentally, this is nearly precisely how another film of the apocalypse, WATERWORLD, begins.

In that film, the peeing is plot-based – Kevin Costner’s character is going to purify and reuse the urine so he can drink it, a campy depiction of how rare water is in that… world. In FURY ROAD, the peeing is character-based, and more importantly, part of the thematic concerns of the film. Water is scarce in this world too, but Max isn’t going to collect his pee to drink it for its water. There’s not that much thought involved. A primal urge is being revealed. Public urination in films, understandably not discussed often by serious thinkers, is nonetheless telling. It’s a borderline aggressive act, animalistic. It’s almost always men doing it. It’s not so much about marking the territory as it is a statement that all the world is our territory. We’ll piss on it because we have to. Max is a junkyard dog – he’s a good dog, but untamed. He’s still a man, and this is the nature of men.

And with that, the film begins, and once it’s in motion, FURY ROAD barely stops.

Since FURY ROAD was first announced, and I cannot even remember when I first heard about it, it had always struck me that George Miller, absolutely one of the finest directors of violent action in the world, had not actually been making violent action movies for a while. After THUNDERDOME in 1985, the then-final appearance of “Mad” Max, Miller made THE WITCHES OF EASTWICK in 1987, proving he could deftly work with stars and their personas, and he made LORENZO’S OIL in 1992, proving he could orchestrate sincere emotion on screen as well as he could carnage. And then, in 1995… he cowrote and produced BABE, an ingenious childrens’ film which combined real animal actors with visual effects. He took over the directing duties for 1998’s BABE: PIG IN THE CITY, an insanely overlooked film even taking into account its growing cult status. 2006 saw the release of HAPPY FEET, a computer-animated childrens’ film about penguins who talk and sing, and 2011 brought its sequel. I’ve only seen the first, and allowing that I wasn’t the target audience, I will say it’s charming but not entirely remarkable – but that isn’t to say it wasn’t valuable. For twenty years George Miller was making VFX-heavy kids’ movies, and now here comes FURY ROAD. I think most people were so happy to be getting a new MAD MAX that they didn’t bother with apprehension, and rightly, but I do think something interesting is sometimes missed that all those years in the trenches with talking pigs and dancing penguins were the perfect “Danger Room” for FURY ROAD, which after all has a couple thousand shots involving visual effects. For all we talk about the brilliant performances and practical stunt work of FURY ROAD, we often forget what a seamless orchestration of technology it is.

Those visual effects enhance the already sumptuous look of the film, which was shot by the legendary Australian cinematographer John Seale in something describable as John Ford meets John Woo. Seale had worked with Miller once before – on LORENZO’S OIL, not THE ROAD WARRIOR. He has a prestige-picture filmography primarily. To examine just one chunk of it, from 1985 to 1986 Seale lensed WITNESS, CHILDREN OF A LESSER GOD, and THE MOSQUITO COAST – but during that time he also shot THE HITCHER and isn’t it fun to think that was probably the most applicable experience from the résumé to FURY ROAD? Seale is now in retirement. What a boss film to go out on FURY ROAD is.

I dwell on each of the major credits on this film as part of my thesis; that every craftsperson in the cast and crew is equally responsible for its success. If any one element wasn’t up to the superlative quality of the rest, you’d notice, and if you were noticing flaws, then you wouldn’t be raving about the cumulative awesomeness of this movie. Of all the credits on any film, maybe the least understood is that of editor. As it’s been said ad infinitum, if you’re noticing the editing choices in a film, the film probably isn’t working. I spent a year in post on a feature film (getting coffee, but nobody was better), and I got to see one of the most successful editors in American film at work, and I still admit I don’t entirely appreciate this art. I do know that Margaret Sixel’s work on FURY ROAD is masterful, because I never notice it, even barely when I slow the film down to study scenes. Sixel is Miller’s wife, but that’s only relevant in how it suggests how important an editor is to the filmmaking process that a great director like Miller wanted to have the person he probably trusts most in the world to spearhead that phase of its creation. FURY ROAD is almost 100% forward momentum. That is because of Miller’s directorial choices, and because of the propulsive score by electronica-producer-turned-film-composer Junkie XL, and because of the fast cars and the furious performances, but what brings it all together, what ensures that all these disparate pieces form one cohesive full-speed whole, is the editing, the choices made with the footage supplied from the work done on set. Film writing focuses on the action on set, the performers, because as I said, it’s easier for people who haven’t done it to comprehend, but also because it’s more inherently dramatic than people sitting around in a room, endlessly playing and replaying footage, connecting it all together bit by bit. But that work is unbelievably essential.

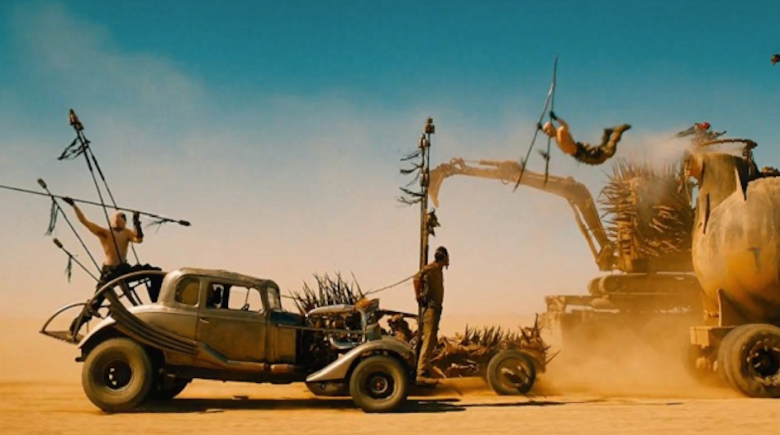

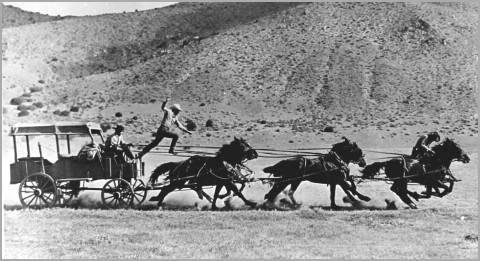

It’s also very possible that having a female eye in the editing room bolstered the effectiveness of the movie’s aims. FURY ROAD is essentially a chase movie. It’s a race through enemy territory, a plot at least as old as STAGECOACH (1939).

MAD MAX: FURY ROAD starts out to be a very male movie. It was written by men. It is directed by a man, with a man directing photography. The film is seen through male eyes. Its male star is the first actor you see on screen.

When Furiosa enters the film, its entire trajectory changes. Again this is one reason I do regret the “First Look” culture of movies. The look chosen for Furiosa by Charlize Theron and costume designer Jenny Beavan is startling. Her head is shorn, with soot as war paint over her eyes. She has an intimidating-looking prosthetic arm, enough to bring down Sylvester Stallone in OVER THE TOP should he dare to arm-wrestle. We see the prosthetic removed more than once before the final moment where it’s ripped off in battle with her mortal enemy. Try to imagine that the moment you sat down to watch MAD MAX: FURY ROAD in the theater back in 2015 was also the very first time you saw Charlize Theron as Imperator Furiosa.

It’s immediately iconic and a unique presentation of femininity, but one that’s many, many, many miles away from the presentation of Charlize Theron in her debut in 2 DAYS IN THE VALLEY, wearing that low-cut skintight white bodysuit. It’s still many miles away from PROMETHEUS and A MILLION WAYS TO DIE IN THE WEST and DARK PLACES, the three movies in which she appeared directly prior to the release of FURY ROAD. A cynic could argue that surely there’s got to be some semi-obscure post-apocalyptic flick from Italy in which there was a bald woman with an arm missing, but it’s not just the look – it’s the fact that a huge-budget action film with a glamorous worldwide star decided to take the risk of making her look this way, and more, the fact that she had agency in that choice. It’s bold as hell. It’s awesome, in the sense of the definition of the world, not its colloquial use (but that too).

Furiosa is capable and fierce and determined and decisive. She is the engine of the plot. Both she and Max get beaten to hell in this movie, but the emotional traveling is all done by Furiosa. We had Max coping with the death of his wife and child all the way back in 1979. That story has been told. No need to look back. This movie is moving forward. In that spirit, Furiosa takes over the narrative fairly quickly in FURY ROAD. It’s Furiosa who goes from a reluctant employee of the tyrannical Immortan Joe, to a defector and a rebel, who liberates Joe’s captive wives. She’s the one headed to her homeland, and agonized to find it gone.

This is the equivalent of Max’s wife and son being run down on that highway. If Furiosa hadn’t already been fully forged in the fires of trauma, she is here. But in MAD MAX, grief led to vengeance. Yes, in FURY ROAD, Furiosa will ultimately topple her arch-enemy (and Joe is hers, not Max’s), but her story isn’t ultimately about the destruction of the villain, but the hope of rebuilding a better world once he’s gone, potentially as its leader. There’s no place for a guy like Max there, and he knows it.

What’s maybe most unique among action movies about FURY ROAD is not even that it introduces a ferocious and mega-charismatic new heroine, but how it coronates her. After their initial disagreements, Max quickly recognizes how capable Furiosa is. As much as he is. Maybe more. Definitely more. When Max realizes there’s a shot he can’t make, he doesn’t just hand her the rifle, he offers his shoulder as balance to steady it. The big tough action hero, the guy whose name is the front half of the title of the movie; after a point, when he notices the potency of his costar, he doesn’t argue. He submits. This is where you have to give Tom Hardy some credit. Can you imagine Mel Gibson doing that?

Furiosa is a character so strong that she’s an eclipse. Her name is evoked by the title of the movie. “Furiosa.” “FURY ROAD.” It’s not subtle, but neither is it immediately obvious, not until you see the movie and get to the end. The movie was MAD MAX: and even mid-title, it allows the FURY ROAD. It’s a revolution in real time. At the end of the movie, the crowd chants for Furiosa and the ex-wives. They chant, “Let them up!” It’s the last line of dialogue you hear, and with any luck, it’s still echoing in your own head as you leave the theater, as you turn off the TV set, as you finish reading this article. “Let them up!” is the final line of the movie for a reason that’s even bigger than movies.

It’s crazy to think that fans waited three decades for a new MAD MAX movie, and now that it’s finally here, the question isn’t even: “Is there going to be another MAD MAX movie after this one?” It’s “Can we please get another IMPERATOR FURIOSA movie?” I don’t know if I’d call that a miracle, exactly, but it’s one hell of a bait-and-switch.

“Furiosa” by @AfuaRichardson.

– JON ABRAMS.

- [THE BIG QUESTION] WHAT’S YOUR FAVORITE FEMALE ENSEMBLE IN MOVIES? - July 22, 2016

- [IN THEATERS NOW] THE BOY (2016) - January 24, 2016

- Cult Movie Mania Releases Lucio Fulci Limited Edition VHS Sets - January 5, 2016

Tags: Abbey Lee, Action Film, Australia, Brendan McCarthy, Cars, Charlize Theron, Classics, Courtney Eaton, Dean Semler, George Miller, Hugh Keays-Byrne, Jenny Beavan, John Howard, John Seale, Josh Helman, Junkie XL, mad max, Margaret Sixel, Mark Sexton, Megan Gale, mel gibson, Melissa Jaffer, music, Namibia, Nathan Jones, Nicholas Hoult, Nick Lathouris, Nick Zinner, Post-Apocalyptic Cinema, Post-Apocalyptic Films, Quentin Kenihan, Richard Carter, Riley Keough, Rosie Huntington-Whiteley, Sequels, Stunts, The Post-Apocalypse, Tina Turner, Tom Hardy, Tom Holkenborg, World Cinema, Yakima Canutt, Zoe Kravitz

No Comments