“There is another woman, and I’m going to find her.” —Baron Frankenstein, Frankenstein (1931)

Femininity and FRANKENSTEIN are inexorably intertwined. Hatched by the daughter of one of England’s most radical feminists, Mary Shelley’s novel savages the hubris of Man with a capital “M” by relaying the tragic tale of Victor Frankenstein, one specifically misguided man who transgresses the laws of nature, victimizing multiple women in his wake: poor Justine Moritz, a servant girl framed for the murder committed by Frankenstein’s abandoned creation; the Monster’s mate, hacked to death before it can be given life; Victor’s beloved Elizabeth, strangled to death by the Creature as revenge. You don’t exactly have to dig too deeply to see FRANKENSTEIN as a sterling example of yet another woman embracing the gothic genre to explore the horrors inflicted upon her gender.

Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley

In the years following its publication, however, Shelley’s novel passed through the hands of several men, including Richard Brinsley Peake, a playwright whose stage adaptation went into production just five years after the book’s publication, and Richard Henry, who transformed the novel into FRANKENSTEIN, OR THE VICTIM’S VAMPIRE. A burlesque take on the novel, Henry’s play represented the novel’s last 19th-century stage production before the burgeoning film medium would take over the reins in solidifying FRANKENSTEIN’s place in popular culture, with men at the forefront of each production, from Thomas Edison to James Whale, whose landmark 1931 adaptation remains the epoch of the tale’s pop culture dominance. Often lost in this, though, is the presence of the other pivotal woman in FRANKENSTEIN history: Peggy Webling, whose play FRANKENSTEIN: AN ADVENTURE IN THE MACABRE was adapted by John L. Balderston for an unproduced Broadway production that caught the attention of Universal.

Peggy Webling

The rest, as they say, was history, especially for Webling, now doomed to be a footnote despite her prolific career as a playwright and novelist. Before she tackled Shelley’s tale, she wrote several novels, plays, poetry collections, and even children’s books. But it was that fateful play for which she’ll always be remembered, at least by those who take a moment to note her name in the credits of the Universal film. Remarkably little is known about such an intricate piece of the FRANKENSTEIN puzzle: despite running for several years and garnering critical attention, the text of the play itself remains unavailable and obscure, known only via second-hand accounts such as Steven Earl Forry’s HIDEOUS PROGENIES, a crucial text charting the novel’s journey to the stage and the screen whose veracity has come under scrutiny in recent years. We do know that the play wasn’t exactly a hit with the London Times, whose critic insisted Webling had “unquestionably succeeded in bringing the monster to life; but the play in which she exhibits this wild beast is as flimsy as a birdcage.” Likewise, Balderston dismissed it as “illiterate” and “inconceivably crude,” which perhaps explains why so many of Webling’s flourishes didn’t survive the translation to the screen.

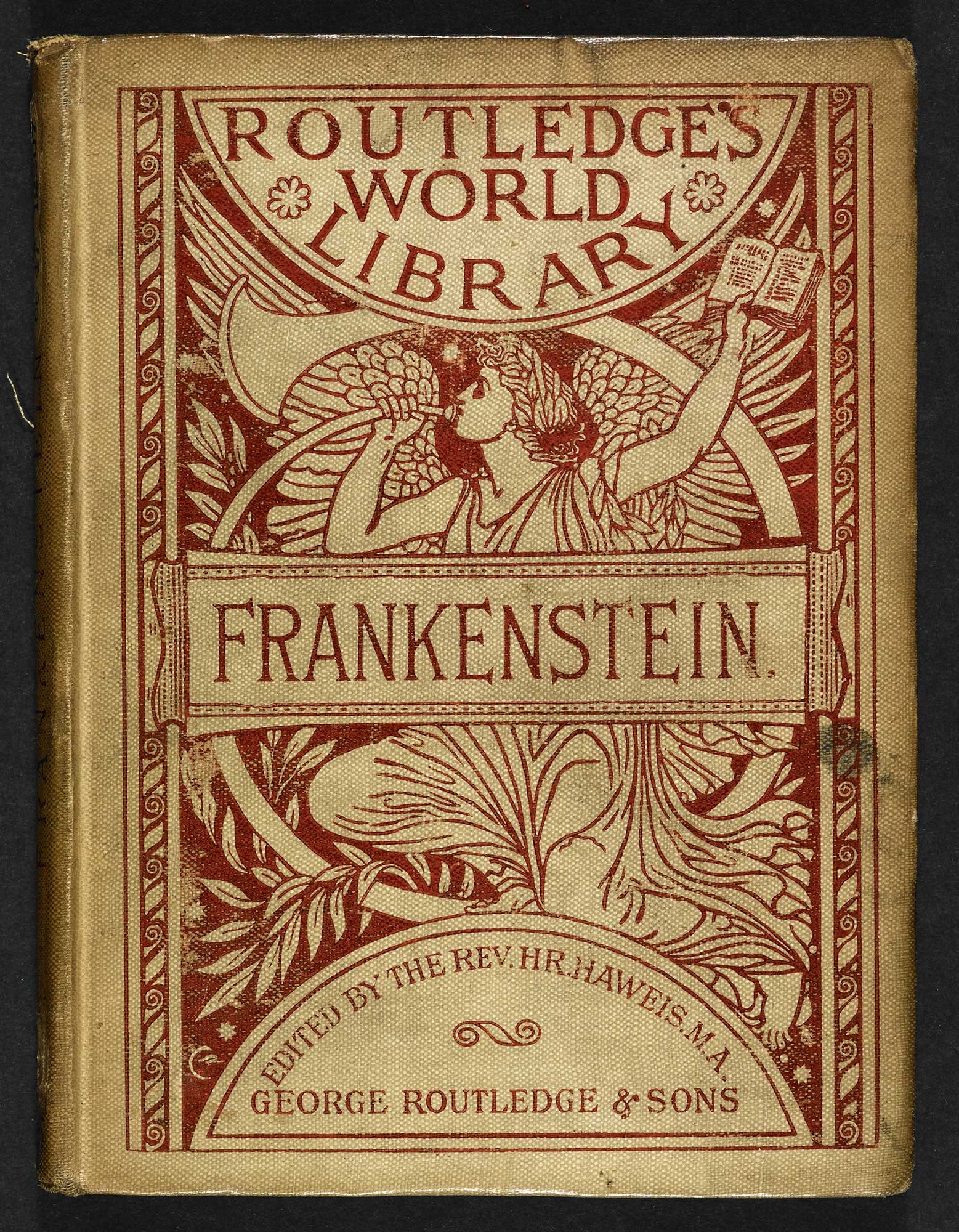

1886 Edition

We also know that Webling’s play was quite a departure from Shelley’s novel, as it finds Henry Frankenstein employing a pair of professors to craft his creation (the film would replace the duo with Dwight Frye’s bumbling Fritz, an import from Peake’s original play—fittingly, the Universal film is a Frankenstein monster in its own right, stitched together from various sources). Instead of the humming, whiz-bang scientific implements that animate the Monster, the play leans on an alchemic “elixir of life.” Professor Waldman—a supporting figure who encourages Victor in the novel and assists him in the Universal film—takes on an even larger role than he has in the eventual film when he connects with and attempts to teach the Monster. Other diversions include the presence of Henry’s extended family, including his mother, father, and a younger sister (rather than the ill-fated younger brother William from the novel) that the Monster drowns off-stage. Much like the infamous drowning of little Maria in the eventual film, the drowning is a tragic misunderstanding; unlike the film, Webling’s play ends with the Creature fleeing for the mountains, where he shares a metaphysical conversation with Waldman before destroying himself, a resolution that admittedly comes much closer to matching Shelley’s original ending than the film’s eventual climax.

Webling’s portrayal of Henry Frankenstein and his creation as doppelgangers—achieved on-stage by having actors wear similar costumes—is also a stark difference, one that may have taken inspiration from Edison’s 1910 silent film. While that production didn’t have the actors sharing wardrobes, it achieves its doppelganger effect by having the Monster appear as a literal reflection of its creator in a mirror. While Webling’s play doesn’t seem to be as symbolic or metaphysical in this respect, it’s interesting to note how both it and Edison’s film may have contributed to the now widespread misunderstanding of the Monster’s identity. The play is a clear culprit here, as it has Henry explicitly name his creation “Frankenstein,” further underscoring Webling’s doppelganger approach. Indeed, as scholar Bruce Graver has noted, her play imagines the duo with a Jekyll and Hyde dynamic, with the Monster representing Henry’s darkest impulses, a notion that didn’t quite make it to the Universal film. Instead, Whale presents Henry and his Monster as a twisted father and son duo, highlighted by Baron Frankenstein’s (Frederick Kerr, whose comedic take on the character has its roots in Webling’s play) obsession with welcoming a son to the house of Frankenstein, tragically unaware that it’s already happened in horrific fashion.

Frederick Kerr

Colin Clive & Boris Karloff

Indeed, had more of Webling’s play survived its various adaptations, the Universal classic as we know it today likely would have been much more different. Whether it would have caught the public’s imagination in the same manner and still help to usher in this era of Hollywood horror will always be debatable. What isn’t debatable, however, is that Webling’s play provided a crucial spark for launching Shelley’s text back into the public consciousness. It’s fitting that Webling’s spark of inspiration has a Romantic slant that Shelley would have appreciated: she was simply walking down the street one day, “turning over in [her] mind the subject for a new play,” when she recalled FRANKENSTEIN, a book she had read years before. Though she initially considered the idea to be “absurd,” she ultimately went with her gut instinct to adapt the novel for a play, unwittingly starting a chain of events that would lead to the story’s most iconic adaptation nearly a decade later.

Unfortunately, it’s also all too fitting that Webling became another woman victimized by FRANKENSTEIN, this time in the form of the virtual anonymity that followed in the years after Universal’s success. Unlike Shelley herself—who published the novel anonymously but later took credit—Webling didn’t garner the acclaim befitting her feat. Of course, Balderston, Whale, and the quartet of screenwriters who solidified that vision deserve all of the credit they’ve garnered—it’s just that none of it likely happens if Webling’s play hadn’t played on a double bill with the stage version of DRACULA that Universal would also adapt. Thankfully, scholars like Graver and Dorian Greenbaum have insisted on highlighting Webling’s role in recent years and restoring her place in a cinematic legacy that has endured for 90 years now. Celebrations are obviously in order for such a momentous occasion, but let’s not forget about Webling, not just as another woman but as the other woman in the FRANKENSTEIN legacy: a woman who had an accomplished career before and after the play that should have made her name as immortal as those who carried her torch.

Tags: Books, boris karloff, Colin Clive, Dwight Frye, frankenstein, Frederick Kerr, History, Horror, John L. Balderston, Literature, Mary Shelley, Peggy Webling, science fiction, Universal Pictures

No Comments