Since the publication of FIRST BLOOD in 1972, John Rambo has occupied a strange space in pop culture. The most reductive — but somewhat true — narrative paints a familiar arc of a character with humble, unassuming beginnings that became twisted into something completely different with each new iteration. The John Rambo of David Morrell’s FIRST BLOOD is a far cry from the John Rambo in RAMBO: LAST BLOOD, largely because shifting political winds and audience whims have carried the character through vastly different approaches and eras, even with Sylvester Stallone remaining steady at the helm. At this point, Rambo is more synonymous with its star than the author who created him, and this cinematic journey has especially contorted — and possibly even distorted — our cultural memory of the character.

Given Rambo’s star-spangled stature in pop culture, it’s sobering to remember that FIRST BLOOD is less a bombastic action picture and more a rugged, intimate thriller where Stallone’s tortured vet spends a lot of time trying not to kill people. The John Rambo of the original film is an avatar for the forgotten victims of a phony war: the American soldiers who returned home harboring trauma and loss, unable to acclimate back to a society that largely tried to forget they even existed. FIRST BLOOD depicts this new domestic war in stark, remarkably anti-establishment terms. Rambo is a wayward veteran trying to track down a fellow soldier, only to discover that his body was eaten up by cancer following exposure to Agent Orange. He eventually runs afoul of a local sheriff who mistakes him as a vagrant hippie and banishes him, an order Rambo defiantly ignores, touching off a small-scale war between the vet, the police force, and the National Guardsmen called in to track him down.

Most of FIRST BLOOD feels like a dispatch from the waning days of a counterculture that pointed its finger at America’s hypocritical moral rot. It’s a film where the war has come home, positioning Rambo is a boogeyman for the right, an agitator who combats authority and dares to insist he deserves the same privileges as anyone else, vagrancy be damned. More frightening, he’s a reminder of the lost war and how the soldiers burdened that loss more than everyone else. Released two years into a Regan presidency dedicated to restoring America’s place as a shining city on a hill, FIRST BLOOD pumped the brakes on notions of restored glory, reminding audiences of the country’s enduring shame.

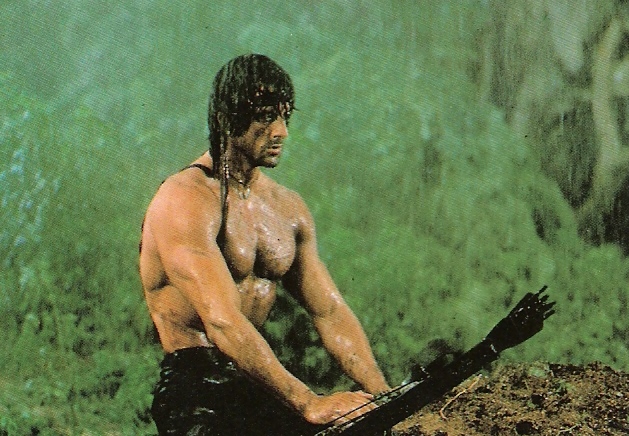

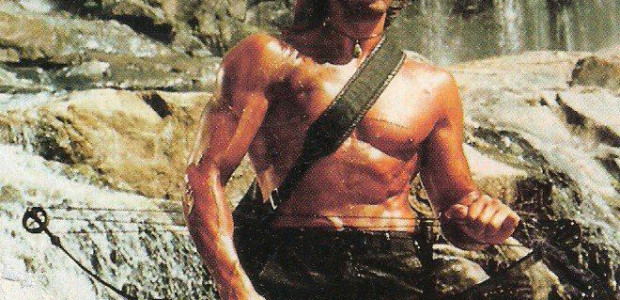

Stallone’s body is not the vanguard of American military might it would become but rather a comparatively wiry vista of torture and trauma. In one of the film’s most audacious scenes, director Ted Kotcheff visually unites the police force’s treatment of Rambo with Viet Cong torture techniques, blurring the lines between America and the Other. Likewise, the sight of a cog in the American war machine leveling an American small town because he “can’t turn it off” — just as he must have done to countless Vietnamese villages — is one of the most confrontational images in ’80s mainstream cinema.

It’s not until Rambo’s climactic speech — when he reaches across the aisle to echo right-wing talking points — that FIRST BLOOD wavers in its staunch anti-establishment position. Here, he rants about the apocryphal anti-war protestors spitting on returning vets and insisting that “somebody wouldn’t let us win,” a pivotal moment where Rambo ceases being a boogeyman and begins to conjure up other boogeymen. It’s not that the war was bad, actually — it’s only bad that bureaucrats made us lose and that some people dared to have a conscience about the war’s very existence. Frankly, it’s a weird turn that somewhat blunts the daring edges of FIRST BLOOD by deflecting the blame from America’s imperialistic complicity to this mythical notion that the country should (and could) have won, moral implications be damned. There’s the sense that Rambo — and by extension, America — might not have become broken if they had just let him win, damn it.

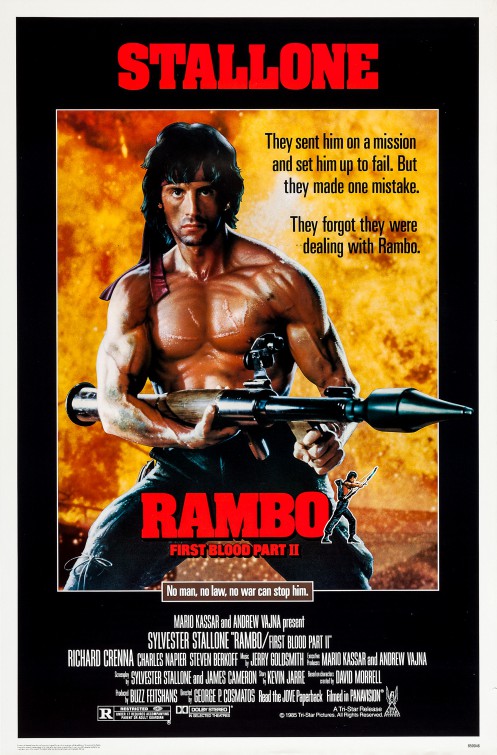

This climactic moment represents the first step in that pivot that would be completed three years later with the Memorial Day weekend release of RAMBO: FIRST BLOOD PART II. Arguably the epoch of the era’s fascination with cinematically re-litigating the Vietnam War, this follow-up takes direction from its predecessor’s climactic rant and little else in the way of tone or style. Rambo, now serving in a prison labor camp, is granted a second chance when Colonel Trautman (Richard Crenna) arrives with a proposition. If Rambo returns to Vietnam and confirms the location of some POWs, he’ll be granted his freedom and possibly even a presidential pardon. Rambo leaps at the opportunity, seeing it not only as a moment of personal redemption but as a national do-over: “Do we get to win this time?” he asks, speaking on behalf of a Moral Majority that craved a chance to bomb Vietnam into oblivion, if only on the silver screen.

FIRST BLOOD II obliges with 90 minutes of sheer carnage, barely any of it guided by the thoughtfulness and conviction of the original. It’s a Regan era fantasy of unhinged “peace through strength” violence visited upon its “rightful” place — abroad, in a Communist nation, where Vietnamese armies conspire with Soviet forces for nefarious purposes, giving Rambo a chance to win the Vietnam War and the Cold War in one fell swoop. Practically a caricature of the man audiences saw in FIRST BLOOD, Rambo grunts his way from one admittedly thrilling action sequence to the next, the unmistakable barbaric yawp of American imperialism echoing with each gunshot and rocket blast. Director George P. Cosmatos’s camera swoons over Stallone’s absurdly chiseled musculature, here fully confirmed as a symbol of American superiority, like a golem carved straight from Plymouth Rock.

Stallone’s script (a heavy rewrite of James Cameron’s draft) pays lip service to Rambo’s tortured psyche via brief exchanges with intelligence liaison Co Bao (Julia Nickson) that allow him to brood about being an expendable, blunt instrument of war. These musings and the relationship he forces with Co speak to a more thoughtful, interesting character work lurking somewhere in the weeds of FIRST BLOOD II, at least when it’s not preoccupied with just blowing shit up in spectacular, jingoistic fashion. On the surface, the transformation from FIRST BLOOD’s conscience-ridden drama to its sequel’s unrepentant violence is complete.

But an interesting subplot emerges when Rambo and Trautman discover that this entire mission is a scam. Rambo is serving at the behest of Marshall Murdock (Charles Napier), a government official trying to placate concerns about stranded POWS. Giving face to those phantom bureaucrats that wouldn’t let America win the first time around, Murdock orchestrates what’s supposed to be a smoke-show: Rambo isn’t meant to actually find POWs on this mission but simply report back that they don’t exist. At one point, Trautman likens the mission to Vietnam itself: a lie that’s put innocent men in peril, a stunning admission from a supposedly right-leaning piece of populist entertainment. For a brief moment, FIRST BLOOD II confronts America’s moral failings in Vietnam, even if it’s talking out of both sides of its mouth while doing so. No, perhaps America shouldn’t have waged this war, but it damn well could have won it if not for the likes of Murdoch. FIRST BLOOD II vanquishes all of the boogeymen at once: the Vietnamese, the Soviets, and the snakelike bureaucrats.

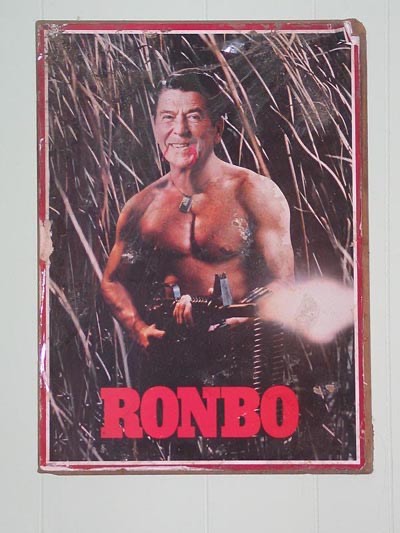

The bureaucrats hint at some discontent over the governmental subterfuge and treachery that flourished during the scandal-ridden Reagan administration. A portrait of Reagan himself prominently beams in Murdock’s office, possibly implicating the president himself in all of this, a notion that undermines the narrative that’s surrounded RAMBO for the past 35 years. What if FIRST BLOOD II is an example of an icon being claimed and co-opted by a group that didn’t know they were actually the film’s villains? While it’s humorous to imagine the 40th president having a “are we the baddies?” moment, we know that Reagan himself enjoyed the film, so much so that he quipped about taking foreign policy direction from it. You have to wonder if he willingly ignored the sight of his own mug nestled right in the viper’s nest of government bureaucrats that serve as one of the film’s villains. Then again, maybe we’re not meant to presume that America itself is somehow broken: it’s just that Big Government — the sworn enemy of Republicans whose mission to drain the swamp apparently involves filling it with more vipers — is bad. Eliminate this middle man and FIRST BLOOD II shows you that one American soldier is more than capable of decimating Vietnam and Russia all at once.

Whatever conscience or anxieties FIRST BLOOD II might posture at seem to be swatted aside so the film can rewrite history through sheer action movie id. Rambo becomes a boogeyman to the Vietnamese, assuming the same guerrilla tactics of the Viet Cong before eradicating them the American way: by guiding a big fucking helicopter into one of their camps and laying waste to it with an infinite supply of machine gun rounds and missiles. No longer an avatar of the aggrieved vet, Rambo is now canonized as an American avenger, one torn himself from the cross of mental and physical torture to wreak havoc on his country’s sworn enemies.

And make no mistake: Rambo is still doing it for his country here. Look no further than the film’s final exchange, where Trautman insists Rambo shouldn’t hate America for selling him out again. It’s quite the contrary, Rambo insists: he’d still die for his country but won’t return home until it loves him and as much as he loves it. Again, you have to wonder how the flag-waving “love it or leave it crowd” ever took to Rambo, an action hero who definitively loved it and left it. America might be great, but one of its most decorated veterans would rather live in exile with Buddhist monks. It’s one of those paradoxical moments that reflects the strange politics of FIRST BLOOD II, a film that simultaneously fulfills right-wing fantasies and highlights its hypocritical penchant of wielding troops as a jingoistic cudgel.

The former obviously resonated more than the latter with contemporary audiences, who made it the third-highest grosser of 1985, but I can’t help but see this as an instance of life imitating art. Just as the American government twisted John Rambo into a killing machine for its own ends, Rambo as a character has become a misunderstood icon in some ways. Those first two sequels especially are wrapped up in such ’80s excess and remain such platonic ideals of the era’s action movies that it’s no surprise that history remembers Rambo as a machine-gun toting, rocket-launching cinematic ambassador of the Reagan administration.

And to be completely fair, FIRST BLOOD II especially doesn’t exactly disavow itself of this notion unless you dig deep enough to realize that Stallone somehow sees Rambo as an apolitical player in a highly political theater. As such, he’s either a victim of America’s disastrous military complex and foreign policy, or he’s a national exorcist for America’s boogeyman-du-jour depending on which sequel you’re watching. Most of the movies surrounding John Rambo may have become American hagiography starting with FIRST BLOOD II, but the character himself has always been more fascinating and complex than his reputation suggests. The ultimate soldier of misfortune, John Rambo has spent his post-war life fighting only when his moral compass suggests it’s right to do so, which is more than can be said for both his on-screen superiors and most of the audience that misappropriated him as a military mascot. Maybe Rambo is ultimately a symbol of the American paradox: a country that wants to be a city upon a hill but has spent much of its existence engaged in violence both at home and abroad. The war can never end for either when violence and a desire for peace are both intertwined in their DNA.

Tags: Buzz Feitshans, Charles Napier, David Morrell, George Cheung, george p. cosmatos, Jack Cardiff, James Cameron, Jerry Goldsmith, Julia Nickson, Kevin Jarre, Mark Goldblatt, Mark Helfrich, Martin Kove, Richard Crenna, Steven Berkoff, Sylvester Stallone, The 1980s

No Comments