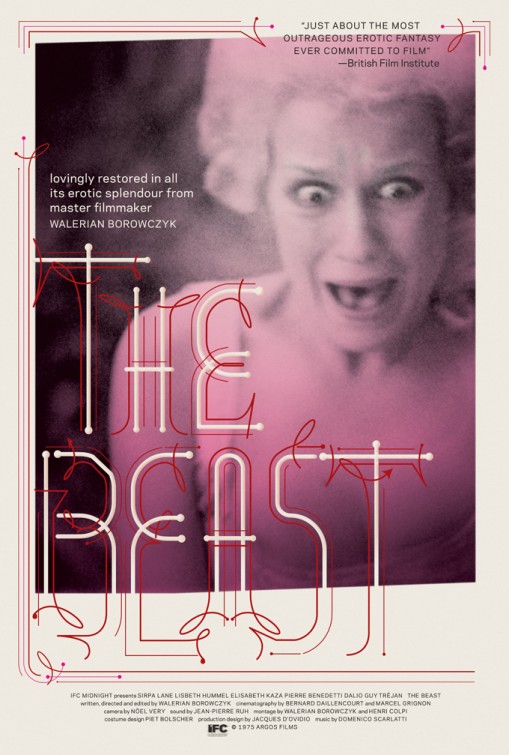

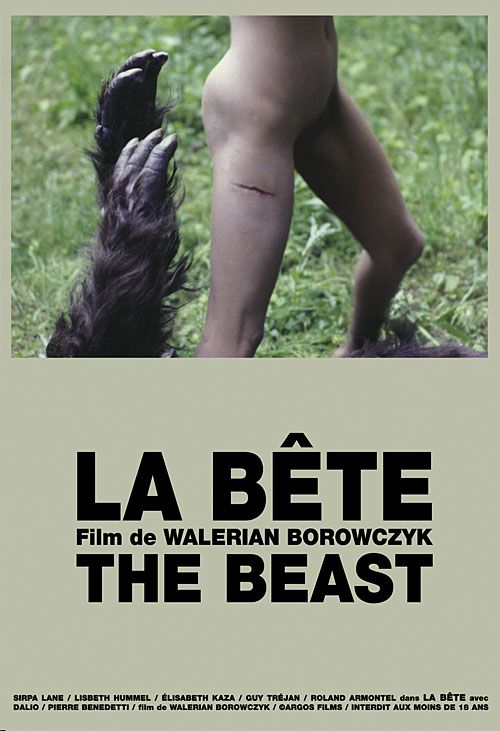

To say that the 1970s were a magical time for onscreen sexuality in France would be an understatement of the highest degree. Jean Rollin’s THE RAPE OF THE VAMPIRE (1968) kicked off the director’s spree of erotic horror films that would see eight produced over the next decade; people traveled all across Europe to come and see Bertolucci’s uncensored LAST TANGO IN PARIS (1972); and in 1974, Walerian Borowczyk released his erotic anthology Immoral Tales, consisting of four stories that each told an “immoral tale” dealing with perversions ranging from masturbation to incest. Met with box office demand upon its theatrical release, the film had already gained critical disdain when it had been presented as a work in progress at the 1973 London Film Festival; the disdain springing primarily from a contentious segment that crossed the lines of good, wholesome erotic tastes and entered into the realms of bestiality and zoophilia. Excised from the subsequent release of IMMORAL TALES, the segment appeared to have hidden its ugly head after the beating it took from the critics that undoubtably patted themselves on the back for protecting audiences from such filth. But they confused hiding with hibernation as the segment prepared to come back, not as a short, but as a feature length film: 1975’s THE BEAST.

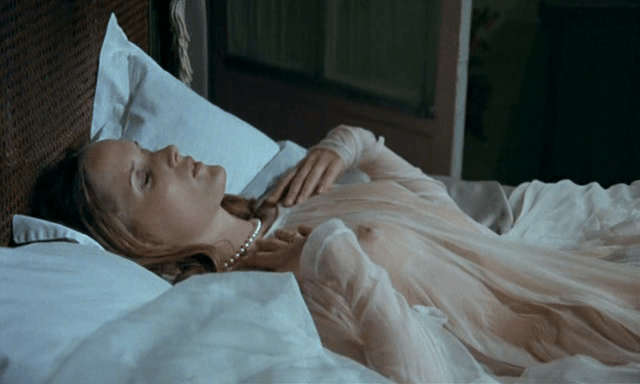

THE BEAST is a film of pure provocation from the opening credits, the title painted in sensual red as the sound of horses mating spill from the following scene, to the fantasy sequence comprised of the previously mentioned footage. Centered around the Marquis Pierre de l’Esperance’s attempts to marry his deformed son to Lucy Broadhurst, the daughter of the late businessman, Philip Broadhurst, who left a will stipulating several conditions that have to be met in order for the marriage to move forward. When a dinner between the two families goes poorly, everyone retires to their rooms; Lucy, having earlier been masturbating to a photo she took of horses copulating, masturbates now with a rose while she fantasies that she is Romilda de l’Esperance, an ancestor of the family who is rumored to have been raped by a local beast 200 years ago. If what I’m describing sounds utterly insane, that’s because it is; a beast, which is clearly a man in a suit, with an enormous member, chases and mates with Romilda, who transforms from a Marie-Antoinette-inspired noble into a nude, short-haired nymphet. While the film attempts to have a narrative flow outside of the fantasy sequence, it’s hampered by the shadow that sequence casts over the rest of the film — at the 59-minute mark, the film enters into a thirty-minute masturbation/beast-sex fantasy, and that can not be overstated.

As far as 1970s erotica is concerned, Borowczyk brought a gun to a knife fight with the release of THE BEAST. The deviant sexuality shown – in the fantasy sequences – and hinted at – like a priest suggestively cuddling his adolescent choir boys – in THE BEAST led to its condemnation and relegation to the ranks of pure pornography when classified with an X-rating. But THE BEAST is not pornography, at least not in its pure form — it’s a parody of pornography. If parody is “an imitation of the style of a particular writer, artist, or genre with deliberate exaggeration for comic effect,” then what could be more of an exaggeration than to present the male figure as a lumbering beast; to enlarge the phallus to horse size; to keep the “money shot” consistently flowing; and to make the opening images pure animal lust.

This critic’s biggest issue with THE BEAST does not stem from its more obvious transgressions but from trying to parse the film’s stance of female sexuality. Lucy Broadhurst masturbates with a rose, the symbol of love and beauty as anyone who’s witnessed Valentine’s Day can attest; however, within her fantasy, she is the one to dominate the beast, and through her repeated sexual actions, she goes so far as to kill and bury it. While a sexual fantasy, separate from the world of the film’s narrative, could be said to lack representation value on the issue, the fact that proceeding the death of the beast in the dream world is the death of the beast in the narrative world, Lucy’s fiance. Connecting the two moments, by placing them back to back in the film, implies that they should be viewed as related; if they are, then is female sexuality dangerous? Even deadly? Or should it be read that her sexuality’s beauty saved her from the beast? It’s a hard question to answer and, perhaps, the most interesting thing to take away from THE BEAST.

Tags: Fantasy, France, Horror, Lisbeth Hummel, Marcel Dalio, Sirpa Lane, Softcore Week, Walerian Borowczyk

No Comments