Cosmic horror, like a number of subgenres, is ill-defined. Unlike other subgenres, however, the lack of a clear definition of what constitutes cosmic horror is ironic. Like the works of cosmic horror themselves, its loose definition is either enticing or frustrating, a spooky come-on or a distancing tease; where things like the slasher and the monster movie have standard formulas to be expected, rules to be bent or broken and comparisons to be easily made, cosmic horror’s only real definition lies in its shapelessness.

Filmmaker Robbie Banfitch’s first full-length feature, THE OUTWATERS, thrives on shapelessness. At first glance, its comparisons online to the recent lo-fi supernatural indie-horror film SKINAMARINK seems out of bounds, as the two films have nothing to do with each other in terms of plot, subgenre or visual aesthetic. Yet both are as good examples as any of the way such highly suggestive horror can act as a Rorschach blot for audience members — some look at either film and see nothing, whereas some look into the abysses provided on screen and fall straight in.

Like SKINAMARINK, THE OUTWATERS is undeniably the work of a singular and complete vision from top to bottom. Being not only the director but star, producer, writer, cinematographer, co-sound designer and special effects creator, Robbie Banfitch has produced something close to a hand-made film here, working with his real-life collaborators and friends. It’s a testament to their talent that THE OUTWATERS never feels amateurish or confused; even in its (many) moments of obfuscation, it always feels like we’re seeing precisely what Banfitch means us to.

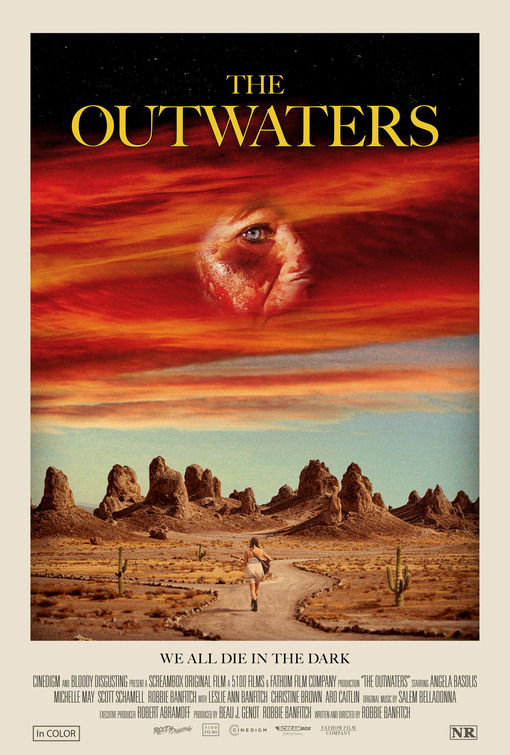

Like the most effective horror films, THE OUTWATERS’ setup is exceedingly simple: an opening sequence where the audio of a disturbing 9-1-1 call is played over stills and titles describing the mysterious disappearance of filmmaker Robbie Zagorac (Banfitch), his sister Ange (Angela Basolis), their brother Scott (Scott Schamell), and Robbie’s girlfriend, aspiring musician Michelle August (Michelle May), removes any doubt about the film’s ultimate tonal destination. From there, we’re presented with “Police Evidence,” three memory cards full of footage taken by Robbie leading up to the group’s disappearance. The first half of the film follows the group as they attempt to put together a music video for Michelle’s new single, a cover version of a traditional lullaby her deceased mother used to sing to her as a child. Robbie’s idea for the video is to venture out to the middle of the desert and capture as much footage as possible, a loose and unconsidered plan that quickly turns dark and deadly.

While most who see THE OUTWATERS will be endlessly discussing its cosmic horror and numerous potential meanings and interpretations, its most impressive but less flashy achievement lies in the way it expertly plays with the tropes and structure of found footage. That particular subgenre has seen its heyday come and go, and while it’s certainly here to stay (like the slasher film), it’s had its formula fully established by now. Banfitch seems aware that, after numerous PARANORMAL ACTIVITY sequels and BLAIR WITCH rip-offs (not to mention reboots), the average viewer is aware of the rhythms of the found footage horror movie. Right off the bat, THE OUTWATERS provides a concrete structure — there will be 3 memory cards only — as well as a plethora of ominous setups and hints of creepy happenings before the group ever get to the desert. To wit: Los Angeles seems to be having a series of unnaturally violent earthquakes, Robbie’s mother in New Jersey calls to say she isn’t feeling well, Scott is mysteriously tight-lipped when it comes to discussing his absent (perhaps deceased) father, and Michelle can’t stop talking about the odd recurring dreams about her dead mother she’s been having.

Once the friends are in the desert, things get even stranger: Robbie finds odd artifacts littered around their campsite, like a vintage bullet shell as well as some creepy-looking bone formations. During their first night sleeping in the desert, the group hear what sounds like an army bombing a nearby battlefield, dismissing it as thunder. The next day, Robbie and Michelle investigate a large, unnatural dirt mound that’s in the middle of the desert floor, believing they hear something screaming inside of it. On top of another hill lies an axe mysteriously buried into it. The next night, in the middle of more bomb/thunder sounds, Robbie ventures out to investigate and sees a figure standing on top of a hill, now brandishing the axe. After what sounds like an attack on Robbie by the figure, reality breaks down considerably, and THE OUTWATERS is off to the cosmic horror races.

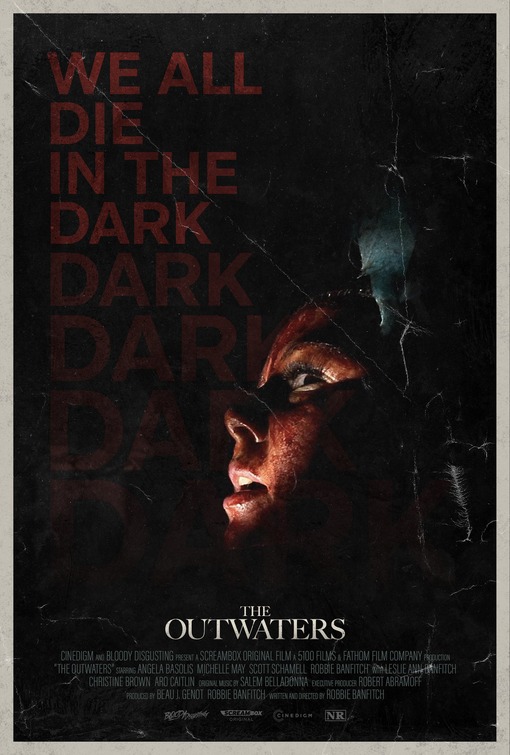

What follows is 45 minutes of surreal, portentous, disturbing and purposely vague footage, and it’s here that THE OUTWATERS either has you under its spell or loses you for good. Those used to the rhythms of, say, the V/H/S films will likely be put off here, as the “setup” portion of the movie is far lengthier than the average down-and-dirty found footage joint. On top of that, precisely none of the first half’s setups are paid off — at least, not in any clearly defined fashion, as Robbie descends further and further into madness, capturing disturbingly depraved things on camera that he may or may not be responsible for. Banfitch knows that most found footage films provide enough context for their spooky goings-on to be deduced — after all, the infamously ambiguous finale to THE BLAIR WITCH PROJECT can be explained if one pays attention to the beginning of that film. Instead, Banfitch purposely declines to provide any concrete interpretation, with about the only sure thing being that Robbie’s footage is intended to be taken as literal since it was found by the authorities — in other words, it’s not a hallucination experienced by Robbie (although one of the setups in the first half of the film sees Michelle explaining how certain hallucinogenic substances reside in a person’s spine forever after being taken, resulting in a new trip if the fluid is properly activated, which may or may not be a red herring).

To offset the film’s low-key and intentionally dark images, Banfitch and the rest of his sound crew provide some of the best and most unsettling sound design to be found in any horror film. That’s not to say the images don’t do any heavy lifting — there are more figures covered in blood here than there are in the first two HELLRAISER movies put together, and there’s even some surprisingly effective creature work to be found, despite the creatures never being on screen for more than a few seconds (or, as in one instance, not properly lit). Where THE OUTWATERS falters is in its lack of payoff. Banfitch does provide an ending, ambiguous and inconclusive as it is. Unfortunately, it’s presented in bright desert daylight, and if you’re not still within the movie’s cosmic horror groove at that point, its imagery can seem embarrassingly try-hard in its grisliness. That’s ultimately the axis where THE OUTWATERS lies: it’s either a spellbinding and bold slice of cosmic horror that pulls you into the void, or a distancing found-footage experiment that is less than the sum of its parts. Like its chosen subgenre, THE OUTWATERS is purposely lacking definition, leaving it up to each viewer to provide one.

Tags: Angela Basolis, Cinedigm, Horror, Leslia Ann Banfitch, Michelle May, Mojave Desert, Robbie Banfitch, Salem Belladonna, Scott Schamell

No Comments