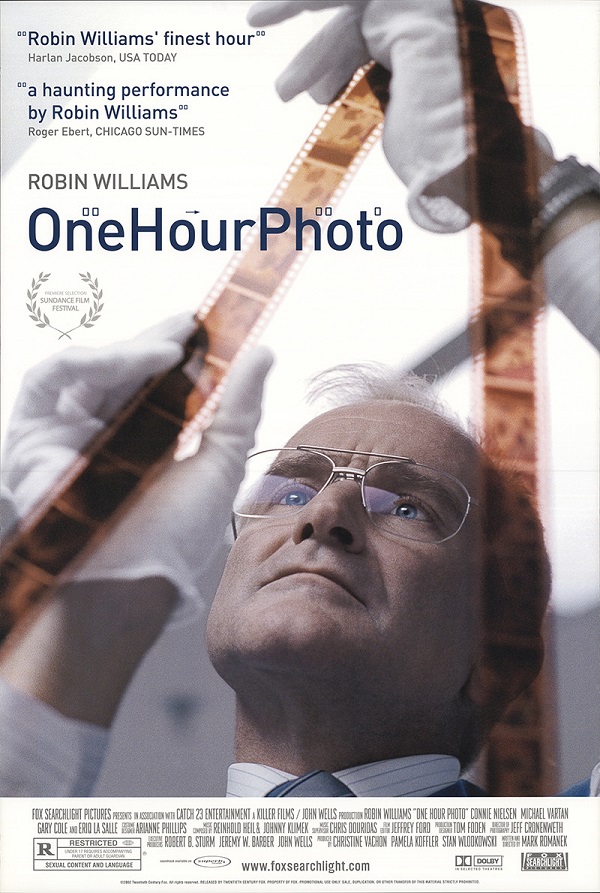

Just as the speedy service of its name implies, ONE HOUR PHOTO arrived at the perfect time. The film premiered in 2002, the same year that cell phone cameras first became widely available to the public. Dancing the knife’s edge between technological obsolescence and prescience, writer-director Mark Romanek’s film examines how parasocial relationships develop through mediated images. Its study of a lonely photo technician and the family whose photos he obsesses over serves as a chilling vision of trauma, isolation, and the media-based fantasies people construct to deal with them.

To younger viewers watching the film today, the idea of a one-hour photo lab might seem quaint or laughable. Lonely photo technician Sy Parrish (Robin Williams) even acknowledges the encroachment of digital photography into what he sees as his calling, as he half-jokingly tells his favorite customer Nina Yorkin (Connie Nielsen) not to get a digital camera because it would put him out of a job. Rather than dating the film, however, its setting and acknowledgment of the coming digital storm lend it a prophetic air. The movie’s themes seem even more relevant in today’s social media landscape than they were when it was released nearly 20 years ago.

The viewer learns early on that Sy is making extra prints of Nina’s photos so that he can pocket her memories for himself. He gazes at them in a restaurant and tells the waitress that Nina’s son Jake (Dylan Smith) is his nephew. Sy has their photos framed in his bedroom as if they were his own cherished family mementos. He stares at them on his lunch break, fantasizing about taking part in a family Christmas. The camera movement throughout the film is fascinating. Wide, static shots dominate, mimicking family photos and emphasizing the viewer’s own voyeurism. We are looking at snapshots of other people’s lives just like Sy does. The scene where Sy fantasizes about opening Christmas gifts, however, uses a method that startles and points the finger at the viewer even more directly.

Jake, Nina, and Nina’s husband Will (Michael Vartan) smile into the camera as dreamy, twinkly music plays. The image moves slightly, as if the viewer is in the Yorkins’ living room actually taking the picture. As Sy’s fantasy continues, the camera pivots; now we are looking at a smiling Sy in a Santa hat, proudly holding up his own present so that we can take his picture too. That turning movement, that slide in perspective, gives the whole scene a surreal feeling that simultaneously tells us how deep Sy’s delusions go and exposes how we are constantly consuming mediated images of our own.

It’s no coincidence that the beloved Robin Williams is playing against type in a film about the relationships we build up in our heads with people whom we have only seen on screens or in photographs. If it’s difficult for viewers to accept Williams as someone who does disturbing things, we have to ask ourselves why that is. Why are we so certain we know someone we’ve never met? The idea of playing against type is itself an indictment of our collective parasocial delusion regarding actors’ public personas. How can we truly know what type of person someone is based solely on watching them pretend to be other people?

Williams was just as talented a dramatic actor as he was a comedian, but — despite all the parasocial implications — it is still deeply unsettling to watch him embody Sy in all his quiet, lonely delusion. Williams’ performance is masterful, capturing every small moment of desperation, sadness, and tightly controlled rage. Its quietness is what makes it so frightening, as is the fact that the viewer sympathizes so much with Sy and his hauntingly empty life. Everything Sy owns — from his clothes to his home furnishings to his car — is drab and nondescript. His life outside the photo lab is eerily monochromatic, yet everything clashes: each item in his home is a slightly different shade of beige. Just like Sy himself, everything seems to be placid and orderly, but the longer you look at it, the more you notice the chaos and disorder underneath.

In keeping with Sy’s disturbingly colorless life, Williams sports bleached hair that renders him even less recognizable (and is likely a subtle nod to Carl Boehm’s Mark Lewis in PEEPING TOM, Michael Powell’s 1960 masterpiece about a mild-mannered photographer who becomes a voyeuristic murderer). Sy’s beige existence is in sharp contrast with the vibrant colors he insists upon in the photos he develops, even going so far as to hand-calibrate the photo-developing machine at the big box store where he works. Sy only truly lives through the images of other people’s lives. Surrounded by white fluorescent light at all times, whether it is at work or at home or in the police interrogation room that serves as a framing device, the only colors in Sy’s world are those he sees reflected through the photos he develops.

It’s easy to extrapolate Sy’s disturbing photo-collecting habits to the world of 2021. Rather than printing Nina’s photos and displaying them in his home, where Sy has a wall filled from floor to ceiling with neat 5” by 7” prints of the past decade of the Yorkins’ lives, today Sy might obsessively retweet a celebrity’s selfies or have a folder on his hard drive for images saved off a stranger’s Instagram account. Even if we might not go to those alarming lengths, social media and increased celebrity worship have cultivated similarly parasocial relationships between us and the people we follow online. Just as Sy imagines himself as a part of the Yorkin family, so too do we imagine ourselves as a part of strangers’ lives based solely on images on our phones or computers. Fandom wars erupt over casting announcements; news of marriages or divorces elicit disproportionate celebrations or tears. We become emotionally invested in carefully constructed narratives that don’t provide a full, authentic picture of a person; we engage in one-sided love (or hate) affairs with copies of copies of PR avatars.

Even when a celebrity isn’t involved, we develop (in our own minds) relationships with people simply by viewing them, by perceiving the images they present to the world, and the inevitable disappointment that comes when we see the vast gulf between reality and the fantasy we have constructed can be dangerously unhealthy. Sy learns that the smiling, perfect family in the Yorkins’ photos is a lie, triggering a horrific violation in the film’s climax that explains why he is in that fluorescently sterile interrogation room. Even after watching Sy commit a heinous act, the viewer still feels for him when we learn why Sy is the way that he is; when the final puzzle piece falls into place, we can’t help but pity this deeply troubled, irretrievably sad man.

That is one of the most frightening things about ONE HOUR PHOTO. We understand Sy. We may not have experienced the trauma that he has; we may not take our parasocial relationships to the disturbing lengths that he does. But we understand him. We see his loneliness and his emptiness and we see ourselves. We watch him try to insert himself into the Yorkins’ lives in order to make himself whole and to feel like he is a part of something, and we recognize our own behavior. ONE HOUR PHOTO puts the camera into our hands and then snatches it back to point the lens right at us.

Tags: Aaron Siskind, Christine Vachon, Clark Gregg, Columns, Connie Nielsen, Drama, Ellen von Unwerth, Erin Daniels, Eriq La Salle, Gary Cole, James Van Der Zee, Jeff Cronenweth, Jeffrey Ford, Jim Rash, Johnny Klimek, Mark Romanek, Michael Vartan, Nancy Burson, Nick Searcy, Nine Inch Nails, Nobuyoshi Araki, Paul Outerbridge, Reinhold Heil, Robin Williams, Suspense, The 2000s, Trent Reznor

No Comments