To celebrate the November 16, 1984 release of A NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET, Nathan Smith and Brett Gallman are spending every day this week reflecting on Wes Craven’s seminal film and its legacy. In case you missed it, here’s Part One.

Part Two

Better Lock Your Door

“Well, he scraped his fingernails along things. Actually, they were more like finger-knives or something; something he’d made himself. They made a horrible sound…”

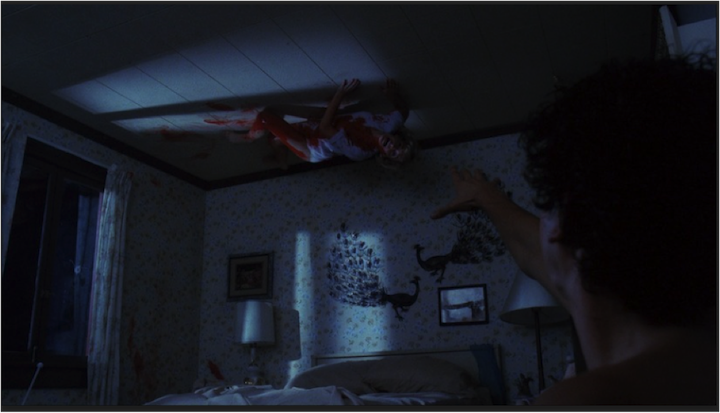

Nathan: A NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET, and its sequels, plays like a greatest hits of horror, with all of its iconic bad dream imagery burned into my brain, but mostly out of context, like clips tethered to a music video (this is why FREDDY’S DEAD: THE FINAL NIGHTMARE has the best end credits sequence—it’s a YouTube compilation that shares some of the craziest sights in a franchise filled with them). There’s Glen getting turned into a blood geyser by our demon dream weaver (an unforgettable death in the hall of fame of horror movie slaughter), the brutal murder of Tina in the bedroom and the accompanying image of Nancy spotting her friend zipped up in a body bag at school. I share your experience, Brett, that initial exposure seemed like you had just watched something that felt different. It was like every other horror franchise was a leveled off painting, and then there was ELM STREET hanging there on a wall, crooked as a politician – a painting in a world without levels. Additional first impressions included my undeniable crush on Heather Langenkamp, which as of the screening I attended last month, yep, still persists. It was also cool to talk about seeing a young Johnny Depp, who all of my elementary/middle school buddies adored from his litany of roles in the ’90s and ’00s (this being pre-trashbag Deppression, of course).

I don’t really recall initially having a relatability to the teens in A NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET, perhaps because I wasn’t a teen when I watched the film for the first few times, and thus didn’t feel the mounting dread that Nancy, Rod, Tina, and Glen had when they come to the realization that they are being slaughtered. As I got older though, the emotional impact really began to dawn on me, when I became aware of my own mortality—which was something that became a fierce, persistent force all throughout my high school years. All at once, these kids weren’t just older than me—they were me. Could I relate to Rod? No, I wasn’t the “ladies’ man” or the “bad boy”, but Jsu Garcia’s fearful performance felt palpable. When I was younger, I always had nightmares where I was guilty of some crime I never committed, so to see someone in flesh and blood be put into an inescapable situation where they’re blamed for a crime they didn’t commit? That’s true horror, and horror that isn’t always restricted to the world of cinema.

But I want to dig into is the violence of A NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET and how it possesses a gravity that all of the other sequels, some more than others, don’t have. Going back to his debut, 1972’s THE LAST HOUSE ON THE LEFT, Wes Craven has always had a sense of the weight of murder, that violence was a ruthless, disquieting act and not something from which people should derive joy. He left you in the immediacy of bloodshed. The visuals of these murders and their aftermaths felt more cerebral than Jason Voorhees running in and cutting a throat in quickly edited/”avoid an X rating” fashion. Craven focused on the grief and the gore, shocking on a visceral and emotional level, while other films (mostly pale imitations) solely focused on the gore. Not many slashers showed the parents discovering that their children have been murdered—outside of this franchise, only FRIDAY THE 13TH: THE FINAL CHAPTER comes to mind. Brett, does the violence in 1984’s ELM STREET still impact you as greatly as it does me?

“She had a nightmare that someone was trying to kill her. That’s why we were there, Mom. She just didn’t wanna sleep alone.”

Brett: It absolutely does for the exact reason you mentioned: unlike most slashers from this era, ELM STREET lingers on the sense of loss that accompanies these deaths. They matter in a way they usually don’t in this genre, where corpses are piled up, only to return as sight gags or for jump scares later on during the climax. There are exceptions, of course, like the part in HALLOWEEN II where Brackett is consumed by grief and rage at the sight of his daughter’s corpse; however, for ELM STREET, this is typically the rule rather than the exception. Like you mentioned, Glen’s death is a perfect example: yes, reducing this kid to an inhuman pile of grue is a staggering sight, but the way Craven dwells on the aftermath is even more unsettling. John Saxon (as police officer and Nancy’s father) sells the hell out of that scene when he looks up at the blood dripping from the ceiling—it’s just so completely, utterly fucked up, and it’s always been that part that got to me. This is the moment when it becomes clear that Lieutenant Thompson and the other adults can’t deny that something beyond comprehension is happening to their children. Even worse, there’s nothing they can really do to protect them, which was really horrific to reckon with when I actually was younger. Freddy and the entire premise of A NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET thrives on a sense of helplessness that always frightened me growing up.

When you’re a kid, you want to believe that something can always be done and that your parents will always be there to protect you. Craven completely upends that notion: not only are the Elm Street parents helpless to save their kids, but they’re the reason these kids are suffering. I don’t know if part of that owed to Craven’s own fundamentalist upbringing, but you’re definitely onto something when it comes to the weight the filmmaker grants to the violence in his movies. In some ways, ELM STREET is kind of an extension of LAST HOUSE, only this time the vengeful parents have to confront the literal specter of their own revenge. Not to stray too far from the topic at hand, but I’ve always been impressed that the later sequels mostly kept this intact, too: the deaths in the NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET movies almost always matter in some way because they usually take at least a little bit of time to grieve and treat its characters with a sense of humanity.

Moving away from the violence for a bit, let’s talk about the story angle that also helped to set ELM STREET apart: the nightmares, which would become one of the franchise’s signature hooks as sequels grew to be more elaborate thanks to increasingly robust budgets. Here, though, Craven has a lo-fi vision of dreamscapes that I think serves the film perfectly: I love that the nightmares in the original film operate on true dream logic. I don’t know about you, but the dreams that linger in my brain are always the ones that feel like real life but are just slightly “off” in some way, and A NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET captures that sensation perfectly. I’ve always particularly loved the bit where Nancy has to step through a random door that takes her from Elm Street to the police station—it makes no sense, yet it makes every bit of sense all at once. It’s a testament to Craven’s talents as a director that he didn’t need much beyond an abundance of fog and some striking visuals to create the impression that you’re constantly submerged in a subconscious nightmare realm—which might make sense, given what the film’s ending suggests. We’ll get to that later, but for now, what do you think about the actual nightmares? You mentioned PHANTASM earlier, a film that operates very much on the same dreamy, elusive wavelength as this one: do you dig that, or are you a bigger fan of what this franchise did with the dreamworld sequences in the sequels?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CMbvJYSTnm4

Please come back tomorrow for Part Three with a deeper dive into the nightmares as well as some thoughts on the culpability of the parents in A NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET.

Tags: A Nightmare on Elm Street, Amanda Wyss, Charles Bernstein, Freddy Krueger, Freddy's Nightmares, Heather Langenkamp, John Saxon, Johnny Depp, Jsu Garcia, new line cinema, Robert Englund, Robert Shaye, Ronee Blakley, Wes Craven

No Comments