Darkened corners, perilous modern landscapes, and distorted, threatening figures; these stylistic elements were designed to throw a viewer off balance. To build an emotional response—unease, dread, hate—so deep it stays with you long after the credits have run. It’s the unmistakable look of German Expressionism, and its emotional triggers are powerful enough to influence filmmakers of horror, film noir, and Gothic cinema nearly a hundred years since first appearing on the silver screen.

But what caused such a dark vision of the world? Well, that’s a horror story all its own.

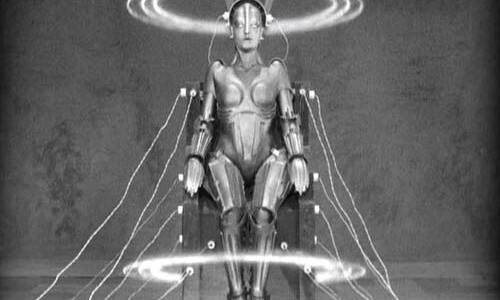

METROPOLIS, 1927

Pre-1910

Before celluloid was available to the masses, artists were tasked with recording the realities of the physical world. They painted and sculpted mankind, monuments and moments in time and acted as reporters who told the story of their experience. In the late nineteenth century when camera equipment became widely available that job was transferred to the masses and the avant-garde artist was left to begin experimenting with a powerful new theme; human emotion.

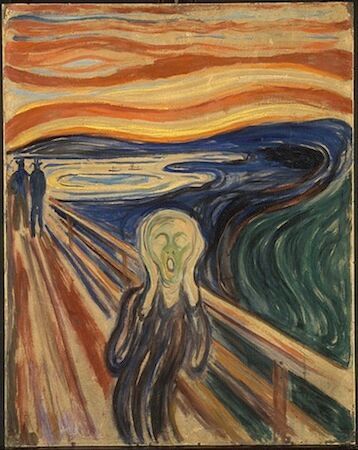

The Scream, Edvard Munch, 1893

Introducing the Expressionists. Van Gogh, Edvard Munch—their art not only gives you the basic information of “who, what, where,” it also delivers an emotional experience that’s based on the artist’s own response to the scene he was creating. Take a look at Edvard Munch’s famous painting, The Scream, if you want to join an artist on his emotional trip.

THE STUDENT OF PRAGUE, 1920

On the heels of these artists another creative group emerged who strove to illicit an emotional response through their art. They began experimenting with new Industrial Age camera technology. They developed multi-angled camera shots, color filters, film layering, and new lighting techniques. They were the filmmakers, and they used all the tricks of German Expressionism to depict how they felt about living in Germany during and after World War I.

METROPOLIS, 1927

1910 to 1913

A new world order was taking over the European continent causing a social realignment that would fundamentally change the structure of society forever. Empires were falling and even the powerless could one day rule the country, if not the world. There was more at stake than ever before.

THE STUDENT OF PRAGUE, 1913

1914

With the outbreak of war in 1914, the German government enforced a boycott on foreign films that created a void in theaters. German filmmakers found their opportunity to get their work in front of larger audiences, and one of the first movies produced was THE STUDENT OF PRAGUE (1913), the story of a man who strikes a deal with the devil. Directors Stellan Rye and Paul Wegener’s use of flat backgrounds, single angle camera work, and rudimentary lighting is proof of the genre’s infancy, but with its dark themes, THE STUDENT OF PRAGUE began to define German Expressionism in cinema.

THE STUDENT OF PRAGUE, 1913

As the war commenced and the Allies began using film to create propaganda, the German government fought back by throwing their support behind Germany’s first production company, Universum Film AG (UFA). Of course, the war department used it to produce propaganda films, but audiences responded most to movies that offered light entertainment. Soon UFA was Europe’s largest film company.

THE GOLEM: HOW HE CAME INTO BEING, 1920

1918 to 1933: The Weimar Republic

War is over and Germany finds itself decimated. Left abandoned by the victors, the economy was in ruins and crime was not only pervasive, it was necessary for many. Theft, murder, prostitution, alcohol and drug abuse were rampant after dark and suddenly Berlin was nothing more than a decrepit Babylon.

THE GOLEM: HOW HE CAME INTO THE WORLD, 1920

Enter THE GOLEM: HOW HE CAME INTO THE WORLD. This 1920 film is very telling when you put it into historical context. Anti-Semitism had yet to gain open prominence in politics and both Germans and Jews were involved in the making of this story of a monster come to life. One of the leading characters is a rabbi, and certainly in retrospect, the storyline is sympathetic to the people feeling social alienation at the time. At the end of the film, the Star of David appears on screen.

THE CABINET OF DR. CALIGARI, 1920

THE CABINET OF DR. CALGARI was also a comment on German society in 1920, specifically about their unresolved feelings about the war and the power of the elite. A powerful but thin-skinned sorcerer controls the people around him through hypnotism, using it to propel them onto murder.

THE CABINET OF DR. CALIGARI, 1920

Within its complicated plot, THE CABINET OF DR. CALIGARI balances themes of authority and conformity, living a double life, point of view and perception of reality. It is considered to be the quintessential work of the German Expressionist era.

NOSFERATU, 1922

Dark and creepy, the 1922 film NOSFERATU by director F. W. Murnau’s is a reinterpretation of Bram Stoker’s Dracula. He uses all the German Expressionism tricks in his tool belt to amp up the skin-crawling foreboding that makes this film a classic which continues live on despite time and technology.

NOSFERATU, 1922

Sharp teeth and claw-like hands, with the pallor of a dead man and the floating gait of a ghost, Murnau creates the vision of the undead that was later adapted by Universal films in the 1930s. And, it’s no wonder, since filmmakers, including Murnau, were beginning to flee Germany for Hollywood.

METROPOLIS, 1927

A decade of troubles left the public discontented and looking for somewhere to place the blame. In the sci-fi epic METROPOLIS, released in 1927, director Fritz Lang utilized elaborate special effects and costly set designs to reflect a feeling of powerlessness and subjugation at the mercy of the elite. Building on themes taken from the Bible (Tower of Babylon), METROPOLIS puts industrialization and mass production on trial. Although Lang was unaffiliated with the Nazi party, METROPOLIS provided future party leaders, like propagandist Joseph Goebbels, a vision of their ideal society.

METROPOLIS, 1927

The End of German Expressionism

In contrast to the genre’s style, German Expressionism did not come to a climatic end, but rather fizzled out naturally when production budgets soared and the boycott on foreign films was lifted. Many of the people involved in developing the cinematic style left Berlin for more prosperous jobs in other countries, but the influence of 1920s Germany film was so innovative that even modern day audiences still respond to its emotional style of storytelling. Look at the films of Alfred Hitchcock and Tim Burton to see two examples of German Expressionism’s legacy in film.

Looking to dive deeper into German Expressionism and its descendants? Take a look at these movies:

THE NIGHT OF THE HUNTER (1955)

Tags: art, Edvard Munch, Europe, Expressionism, F.W. Murnau, Germany, Max Schreck, Paul Wegener, Stellan Rye, World Cinema

No Comments