Last week, breaking a long tradition of willful ignorance, I read a few articles about GODZILLA before I had a chance to see the movie. Each of the articles came to the same conclusion: yes, GODZILLA doesn’t really seem to care about its human characters, but it appears to be more of a conscious decision by the filmmakers rather than a failing on the part of the script. When I finally had the opportunity to see GODZILLA later in the week, I found myself thinking about the transitional role of the human characters in the film. Had I known nothing going in, I likely would have joined the chorus of people complaining about the lack of character development in the film’s second half. Instead, I embraced the emptiness and started thinking about video games.

Many people complain about the effect that video games have had on the film industry. When a critic compares a film to a video game, it is as much a shorthand to describe the film’s failings (character development, nuanced performances) as it is praise of what the film does well (action set pieces, visual effects). As GODZILLA moved into its second half and began to flirt with epic monster sequences, I found myself impressed by the way that director Gareth Edwards was able to incorporate video game elements into the film without calling attention to his own intertextual bravado. Many filmmakers attempt to re-create moments from famous video games on the screen; Edwards has broken down the design elements and translated them perfectly to a different medium.

In film, perspective is dictated by an object’s relation to the camera. While something with a physical presence may walk off-camera and assume to still exist, none of the computer-generated monsters in GODZILLA can exist outside of the frame. Therefore, Edwards and his crew must make a conscious decision of where to place the creatures. Most monster movies stage their set pieces in the center of the screen; even directors such as Jonathan Liebesman, known for his chaotic staging and “shaky-cam” aesthetic, still allow the creatures to be framed almost entirely within the shot. We are not often called upon to question the diegetic world surrounding the mise-en-scène because most of the necessary information is conveyed within the framing.

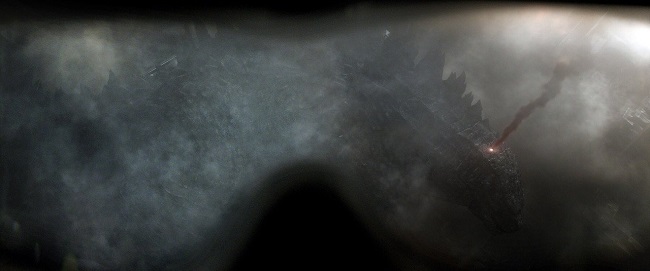

This contrasts directly with the world that Edwards and his crew created on the screen. In order to give Godzilla and the MUTOs a sense of size and scale beyond that of apocalypse blockbusters like PACIFIC RIM or THE AVENGERS, Edwards takes two common video game principles and alters them to fit his vision of the story. The first principle is that of limited perspective. While the audience is not solely limited to seeing the world through Ford Brody’s eyes, we are often rooted in his perspective. This means looking up to see Godzilla and allowing the screen to be filled with only part of the image; Brody’s relative size does not allow him to view Godzilla in his entirety, and Edwards is not afraid to show only Godzilla’s legs or tail to offer a sense of size. Keeping the camera close to Brody—either on the ground or when elevated—keeps the size of things in perspective throughout.

Edwards also frequently reminds audiences that the action is occurring all around his characters by adopting the video game’s sense of three-dimensional space. In the above description of perspective, the information is portrayed relative to the camera’s position. Edwards utilizes the full 360 degrees available to him and choreographs the action sequences on two different levels. On the first level, Brody navigates the ruins of downtown San Francisco as he tries to complete his mission and locate the nuclear device; on the second (larger) level, Godzilla and the MUTOs wrestle their way through the rubble of the city.

Compare this to the action sequences of a game like Gears of War, where the player is occasionally prompted to zoom in on “Points of Interest” that may be far away or high above the avatar’s head. A monster movie depicts the action as being relative to the camera position, but a monster game flips the script and surrounds the player on all sides with action, allowing the player control over where to look. Should Godzilla appear only on the edges of the screen or partially out-of-frame, it is necessary to emphasize the full range of action occurring in the film. Edwards steps outside the traditional concept of cinematography—camera dictating action—to dabble in a persistent environment more familiar to game developers, where action itself dictates where the camera should point and where the instincts of the player can determine the clarity of the shot.

And if GODZILLA is filmed based on principles contained in game design, then that must make Elle and Ford Brody the avatars through which the audience experiences the fights. Many reviews have been critical toward the human element of GODZILLA; most critics highlight the tension between how the humans are treated as secondary characters to the monsters in terms of development but are still given the majority of screen time. If audiences are supposed to view the monsters through the eyes of humanity—able to glimpse only a portion of the action due to their relative size—then it is not too much of a leap to suggest that Aaron Taylor-Johnson and Elizabeth Olsen are primarily meant to be vessels for how the audience views the action. We see their faces and get a hint of their motivations, but in any way that matters, they are the silent protagonists of GODZILLA.

The silent protagonist trope is an element of video game design meant to provide a deeper immersion into the game’s virtual environment. Critical favorites such as Skyrim and Fallout 3 provide gamers with blank slates onto which they can project their own desires to create unique user-generated gameplay experiences. The two aforementioned games pluck their protagonist seemingly out of obscurity and unleash them into a world previously unseen to them. Anything these characters know or experience happens through the user gameplay. While the medium of film does not allow audiences to project themselves onto the screen, by keeping Taylor-Johnson and Olsen devoid of personality—both characters are attractive, competent, and moral throughout, characteristics meant to capture the broadest possible appeal—Edwards and screenwriter Max Borenstein are able to construct the perfect conduits for audiences to view the rampage in San Francisco.

The director and writer emphasize the role of the Brodys as avatars by keeping the goals of the characters simple. Ford bounces from one military operation to the next, given direct orders that will ensure his continued presence on the frontline. Similarly, Elle sends her son away but refuses to leave the hospital; the only tension in the human element is how to keep both characters near the action without sacrificing their roles as our competent and moral surrogates. As the audience’s avatars, our interest in their success is rooted not in character development but the continuation of our voyeuristic enjoyment. So much of the action is rooted in their ground-floor perspective of Godzilla and the MUTOs; their deaths would, like any other video game, bring the immersive experience to an end.

So while no one in their right mind would compare GODZILLA to other contemporary video game adaptations such as RESIDENT EVIL or MAX PAYNE, there are certainly elements of Edwards’s film that have their roots in game design. And while it may be true that unclear action sequences or poor character development are often to be avoided at all costs, filmmakers do not frequently dig below the surface of video games to find elements that can translate effectively to the screen. GODZILLA may just be the best video game movie of them all, and for once, that’s not damning with faint praise.

— Matthew Monagle (@labsplice)

- [THE BIG QUESTION] WHAT’S YOUR FAVORITE FEMALE ENSEMBLE IN MOVIES? - July 22, 2016

- [IN THEATERS NOW] THE BOY (2016) - January 24, 2016

- Cult Movie Mania Releases Lucio Fulci Limited Edition VHS Sets - January 5, 2016

Tags: GARETH EDWARDS, GODZILLA

No Comments