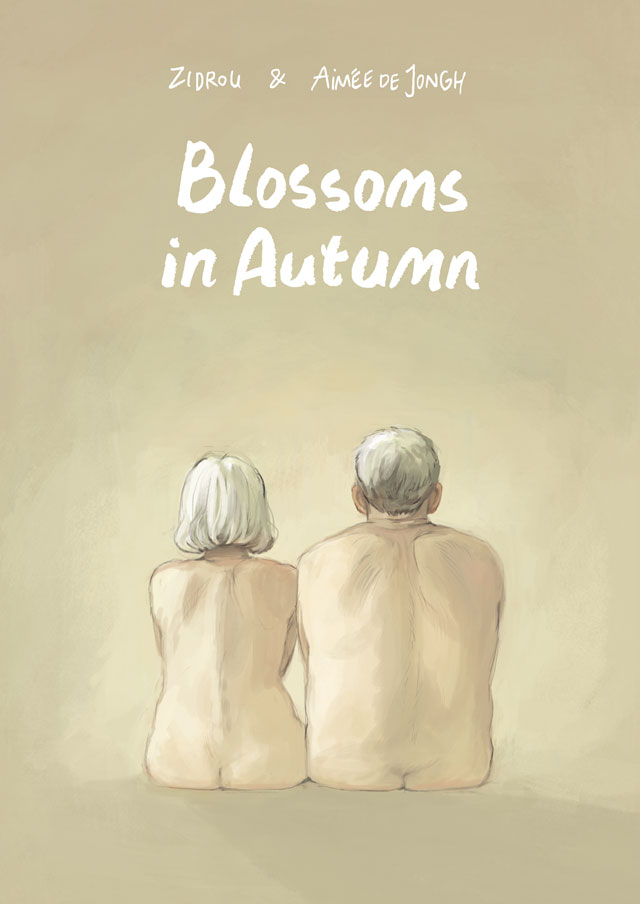

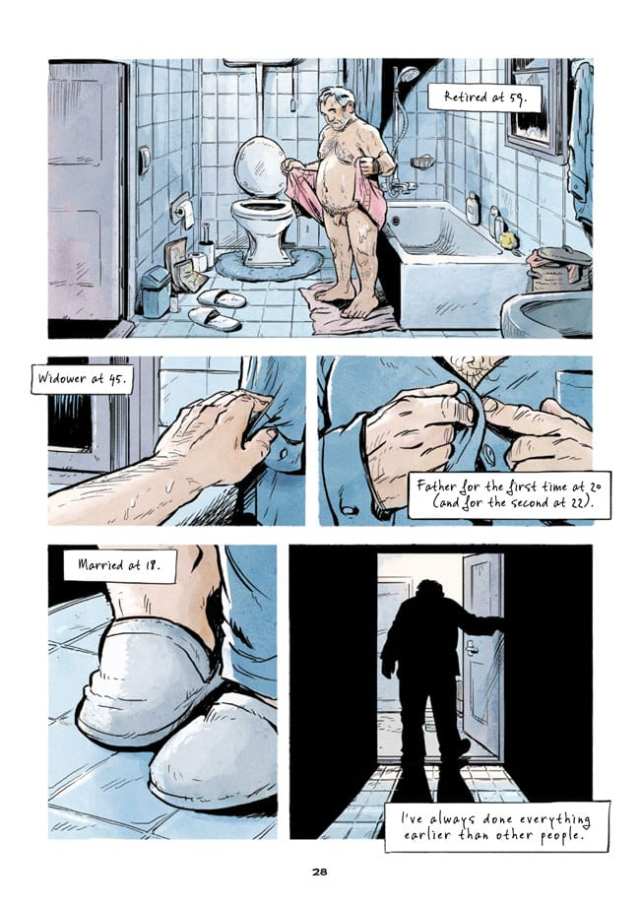

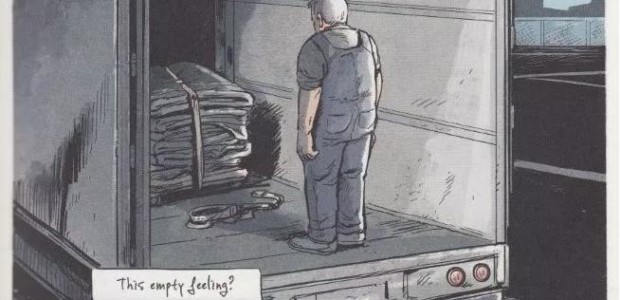

There’s really so much to like about Belgian writer Zidrou and Dutch artist Aimee de Jongh’s Blossoms In Autumn, recently made available in a hardcover English translation from upstart UK small press powerhouse-in-the-making SelfMadeHero — the story of late-life romance between 59-year-old widower Ulysses, recently forced into early retirement from his job as a mover, and 62-year-old- former-model-turned-cheese-shop-owner Mediterranea is nothing if not absorbing, wistful, endearing (frequently in spite of itself), and gorgeously illustrated.

It’s also important in that it shines a light on a subject too often neglected by all media, yet rife with untapped potential and possibility — I mean, we all know lonely older folks need love too, maybe more than anybody, and yet the sexual and romantic lives of elders are constantly ignored by movies, television, literature, and comics. Go ahead and insert an “of course” after that last one, in fact, since this is probably the first comic I’ve read specifically devoted to a narrative about old-timers finding their potential soulmates in the “third act” of their lives.

Certainly both protagonists are “likable” enough, in the broadest sense of that term, and the creators do a nice job of putting readers “on their side,” essentially making us wish for the best for them from the moment they meet — the problem, however (and you knew this was coming), is that while the art is consistently evocative, emotive, and expressive, the scripting is often, for lack of a kinder way of putting things, too damn calculated for its own good, and falters even more when Zidrou strays from his cliche-riddled blueprint.

He certainly doesn’t shy away from cloying sentimentality, let’s state that for the record right now, going overboard in portraying the ennui and loneliness of both Ulysses and Mediterranea, even though he’s got plenty of family and she’s got plenty to keep her busy. We don’t need to feel sorry for these characters in order to care about them, but the script here goes the cheap and easy route, making an overt play for sympathy from the outset and really never letting up. Subtlety? Not gonna find it here.

Which wouldn’t bother me so much in and of itself if it was contained to our principal players, but it extends in all directions: a sex worker a good couple of decades his junior who Ulysses frequents is secretly in love with him, Meditteranea’s sole employee is a female ex-con who her family took in and immediately treated as one of their own, etc. Everyone is a central casting cardboard cut-out placed within the narrative to reflect well upon our lovebirds. It gets pretty old (sorry) pretty fast.

It also undercuts so much of what the book does have going for it — the first sex scene, superbly and fluidly rendered by de Jongh, comes off as a “and then the gates of heaven flew open” moment, when a bit more naturalistic awkwardness and trepidation would have been the smarter and more accurate way to go; courting rituals that could and should have been endearing for their imperfections are entirely too smooth and easy, etc. When you toss in the bizarre inconsistencies in characterization referenced briefly earlier — Ulysses tells Mediterranea that he used to jerk off to her magazine covers when he was a young whippersnapper on their first unofficial “date,” and mere pages later is talking about how he’s a shy guy who takes things slow; his son goes from being happy for his old man to concerned about what the future portends and back again with nary a whit of transition; etc. — the whole reading experience comes off as a jarring contrast to the consistently breathtaking (and, it’s gotta be said, perfectly colored) art. Pictures this gorgeous deserve a story to match, rather than being forced to carry the entire load.

And then there’s the ending — look, I’m not going to “spoil” anything here, but again, it’s so clumsily handled that its impact is entirely negated. What happens to and for Ulysses and Mediterranea is a bona fide miracle, one with the potential to divide readers in truly gutsy fashion (and thus ensure this would become a very “talked about” book, indeed) but it’s telegraphed at about the halfway point of the story, becomes the primary focus of the “final act,” and has lost all power by the time it’s made, well, “official.” More wasted potential, then.

Which is really a running theme here, come to think of it. I’ve flipped through Blossoms In Autumn many a time since finishing it to “ooh” and “aah” at the artwork, but de Jongh — and even the characters whose lives she delineates — have earned much better than what they’re given here, story-wise. Between the glaring shifts in characterization and the over-reliance on the crutch that is melodrama and sentiment, what could have been a groundbreaking tale about a fascinating and overlooked facet of real life is instead reduced to Craig Thompson for the senior set.

Tags: Aimée de Jongh, Benoît Drousie, Columns, Comic Books, Comics, SelfMadeHero, Spain, The Netherlands, Zidrou

No Comments