Daily Grindhouse is proud to present the work of Jason Coffman, one of the finest writers on film we could name. Jason works harder and sees more than pretty much everybody, and if you aren’t already familiar with his work, you’re going to want to be. Jason recently finished his annual film round-up for 2016 over on Medium, and gave us permission to run it here also, since this is the caliber of writing that deserves every last eyeball we can get on it. Read on and see for yourself!

2016 Film Round-Up:

Honorable Mentions, Special Recognition, and Favorite Documentaries

20. River of Fundament (USA, dir. Matthew Barney)

Matthew Barney’s previous films, especially some of the Cremaster series, suffered from occasional technical issues — iffy videography, bad CG—that distracted from the ambition and imagination of the work. Those issues are nowhere to be found in River of Fundament, which almost unbelievably represents a huge leap forward from his previous work from both a technical standpoint and in its ambition. Shot in gorgeous 4K digital video, River of Fundament is a tribute to the late Norman Mailer (who Barney befriended in his later years, and who appeared in Cremaster 2 as Harry Houdini) in the form of a 5+ hour body horror nightmare opera.

This is a lot closer to traditional narrative than Barney has ever gotten before, but it’s still most immediately accessible as an epic fever dream that drowns the viewer in one beautifully shot, jaw-droppingly bizarre set piece after another. The characters nearly all sing-speak, and Barney’s musical collaborator Jonathan Bepler’s score and songs are as alien as ever but also occasionally veer into familiar pop territory that feels even weirder in this context than any of the other unusual sounds he incorporates into the pieces. Seeing this in a theater with a good surround system is essential, as Bepler takes full advantage of the sound field to immerse the viewer completely in this world.

As its title suggests, anyone who is at all skittish about bodily fluids will absolutely want to give this a hard pass. And anyone who hates Barney’s previous work will probably not be interested in watching this anyway, but even if they did it’s unlikely this film would change their opinion. But there’s no question that River of Fundament is unlike anything you’ve ever seen before, even if you’ve seen all of Barney’s previous films.

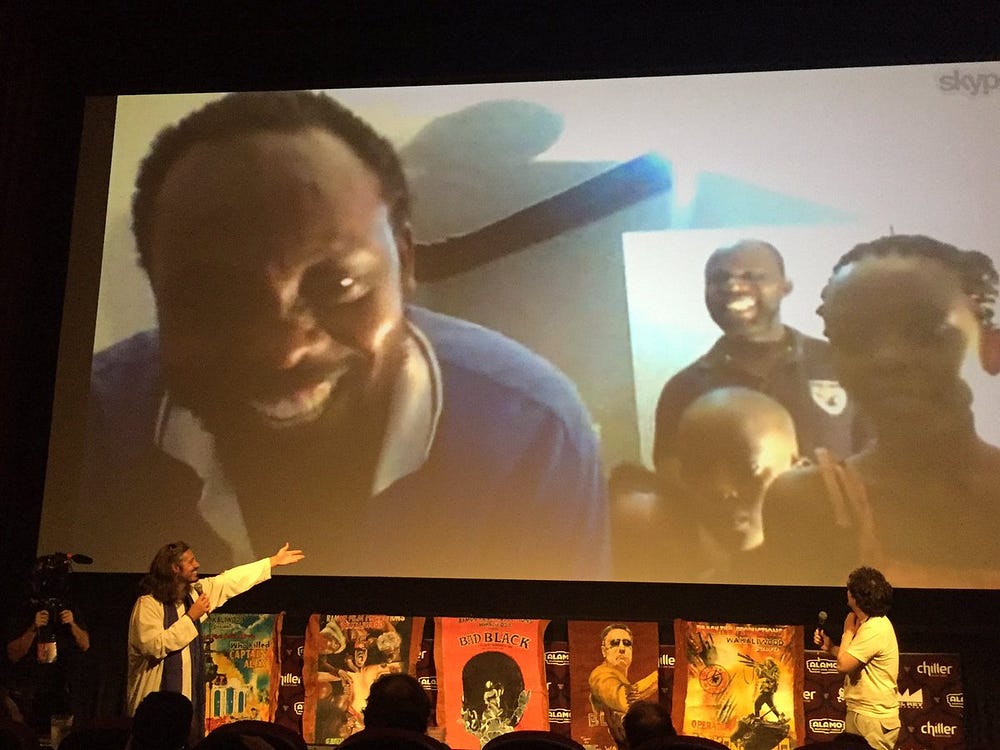

Bad Black (Nalwanga Gloria) runs a team of criminals in the slums of Kampala. She schemes to bring down the rich man Hirigi (Bisaso Dauda) and steals dog tags belonging to American Doctor Ssali (Alan Hofmanis). Ssali’s kindergarten-aged assistant — named, hand to God, Wesley Snipes — trains him to become a badass to get his dog tags back. But what is the real story behind Bad Black? Why is she so intent on bringing down Hirigi? And how many people is Dr. Ssali willing to kill to get his dog tags back? Bad Black is the latest import from Ugandan production company Ramon Film Productions, the same people who made Who Killed Captain Alex? a few years ago. Alan Hofmanis moved from New York to Uganda to help with the production and distribution of the movies, and has been enlisted as “America’s best action star.”

Ramon Film Productions is an example of a hyperlocal cinema, made by (and basically for) the people who live in one particular neighborhood of their home city of Kampala. That area is called Wakaliga, and they have named their industry “Wakaliwood” in its honor. Shot on cheap digital video and using an impressive array of handmade props, Bad Black would be hugely fun even if it wasn’t for the appearance of VJ (“Video Joker”) Emmie providing a running commentary on the action: for example, when Ssali guns down a couple of guards, Emmie shouts “Worst doctor ever!” This kind of thing is best seen with an audience, and seeing this labor of love with a game crowd at Fantastic Fest was an amazing experience. Hofmanis even brought along a machine gun prop built for the movie out of old car parts and the audience passed it around during the post-screening Q&A, which was a highlight of the fest. Wakaliwood’s pure love of movies is infectious and irresistible, making Bad Black one of the most weirdly joyful moviegoing experiences of the year.

18. Women Who Kill (USA, dir. Ingrid Jungermann)

Morgan (writer/director Ingrid Jungermann) and her ex Jean (Ann Carr) have a popular podcast on female serial killers called “Women Who Kill.” One day at the food co-op where Morgan volunteers, she meets the mysterious Simone (Sheila Vand) and unexpectedly finds an instantaneous mutual attraction. While Morgan and Simone start spending more time together and a tragic event occurs at the co-op, Jean starts to suspect that Simone may be more than just a fan of the podcast—and that Morgan’s life may be in danger. Women Who Kill is a sharply written, wryly observed comic thriller that is more about the characters and their relationships than any genre trappings that surround them. Buoyed by a great supporting cast including Annette O’Toole (who also turned in a great, totally different kind of performance in Jesse Holland & Andy Mitton’s We Go On this year), Jungermann, Vand, and Carr provide a strong emotional center for the increasingly dark territory into which the film moves in its final act. It’s understated but frequently laugh-out-loud funny, and it’s a strong feature debut for Jungermann.

17. Colossal (Canada, dir. Nacho Vigalondo)

Alcoholic, unemployed writer Gloria (Anne Hathaway) is kicked out of the New York apartment she shares with her boyfriend Tim (Dan Stevens) after one too many all-night benders. She moves back upstate to her hometown into the house she grew up in, and her childhood friend Oscar (Jason Sudeikis) hires her to work part-time in the bar he inherited from his father. The next day, a giant reptilian monster appears in Seoul and stomps across part of the city. Gloria realizes that she is somehow responsible and has to make it right, but then the situation unexpectedly gets a lot more complicated. Colossal is a deft blend of indie relationship comedy/drama and giant monster movie, two completely different styles of film that seem totally at odds with each other. But writer/director Nacho Vigalondo cleverly points the story in directions that make the central conflict(s) of the film echo in unexpected ways. Hathaway gives a great performance acting against type, but Sudeikis steals the show in a part that is also considerably different than any he’s done before.

16. Krisha (USA, dir. Trey Edward Shults): Amazon, Google, iTunes

After a decade-long absence from the lives of her son Trey (writer/director Trey Edward Shults) and her extended family, Krisha (Krisha Fairchild) returns for the family Thanksgiving celebration at her sister’s home. Krisha is eager to make amends, especially with Trey, but the wounds she has left in her wake after a life of addiction and irresponsibility run ragged and deep. As the day drags on Krisha battles with despair, her own inner demons, and the people she loves but that she has repeatedly hurt and disappointed.

Krisha is a truly harrowing film, drawing on the same kind of primal terror that can only be inflicted by the familial that makes Andrzej Zulawski’s Possession such a difficult viewing experience (although without that film’s surrealist genre trappings and hyperstylized acting and direction). Debut feature director Trey Edward Shults focuses on Krisha’s experience at the center of a lot of very bad vibes coming from all sides: her son’s reluctance to engage with her, her brother-in-law’s frank disdain for her lifestyle and choices, her mother’s deteriorating mental state, and the pressure of being in charge of preparing the massive turkey for the family dinner. Krisha Fairchild gives one of the absolute best performances in any film this year as the title character, which only makes the film even tougher to watch. It’s punishing, terrifying, and heartbreaking, and it’s easily the best Thanksgiving horror movie ever made.

15. They Look Like People (USA, dir. Perry Blackshear): Amazon, Google,iTunes, Netflix

Wyatt (MacLeod Andrews) drops in unannounced on his old friend Christian (Evan Dumouchel) in New York. Christian, reeling from a traumatic breakup, is confused but excited to see his old friend. What he doesn’t know is that Wyatt has come to the city in hopes of saving Christian from a coming apocalypse: monstrous creatures that take the form of humans are growing in number and power. As Christian struggles to advance at his job and listens to motivational tapes, Wyatt tries to keep his head while he gets mysterious phone calls on a broken cell phone warning him to get out of the city before it’s too late. Perry Blackshear’s They Look Like People is a compelling hybrid of low-key drama and psychological horror with a sense of humor that helps relieve some of the claustrophobic tension. It’s also one of the best cinematic depictions of schizophrenia since Lodge Kerrigan’sClean, Shaven. The central relationship in They Look Like People is one between two life-long friends, and the excellent leads make that relationship totally believable. That center makes They Look Like People funny, scary, and moving. That’s a tightrope walk for the best genre filmmakers, but debut feature director Blackshear makes it looks effortless.

14. Sweet, Sweet Lonely Girl (USA, dir. A.D. Calvo)

Adele (Erin Wilhelmi), a young woman living with her pregnant mother and her mother’s lecherous boyfriend, is sent to care for her agoraphobic aunt Dora (Susan Kellermann) in her imposing Victorian home. Dora refuses to leave her room, communicating mostly through handwritten notes slipped under her door. When Adele meets Beth (Quinn Shephard) while out running errands, the two young women strike up a friendship. But Adele’s restlessness and Beth’s influence cause Adele’s relationship with Dora to change, possibly setting them on a tragic course. Sweet, Sweet Lonely Girl recalls ’70s “psychotic women” films, but unlike other recent throwbacks to that era it is more tonally reminiscent of regional horror films from the ’70s and early ’80s like The Folks at Red Wolf Inn and Don’t Look in the Basement. This is a film that would ideally be first seen by impressionable horror fans late at night on a local television station, through a light sheen of static. It’s much more artful than that comparison might suggest, though. The simple but effective score and gorgeously autumnal look of the film, as well as a pair of solid, understated performances by Wilhelmi and Quinn all help to create a powerfully creepy atmosphere.

13. Arrival (USA, dir. Denis Villeneuve)

When twelve alien ships suddenly appear all over the globe, linguist Dr. Louise Banks (Amy Adams) is enlisted by the government to attempt to communicate with the creatures that landed in the midwest. Joined by physicist Dr. Ian Donnelly (Jeremy Renner), Banks manages to make progress but the operation is threatened by the tensions between governments of the world and the pervasive civil unrest that follows in the wake of the arrival. Arrival is an intelligent, mature, and emotionally affecting science fiction feature. It deals with some seriously heady material but manages to never feel aloof or inaccessible even though it doesn’t go out of its way to dumb anything down for a wide audience. It’s frankly a miracle that it was produced by a major studio in the current climate of superhero blockbusters and endless sequels. Amy Adams is perfectly cast and leads an ensemble of great performances, and Denis Villeneuve proves again that he’s one of the best and most interesting directors working at this level.

12. Fashionista (UK, dir. Simon Rumley)

Married couple April (Amanda Fuller) and Eric (Ethan Embry) run a vintage clothing store in Austin that their whole lives revolve around. They’re still reeling from a failed business partnership that they sunk years into when April starts to suspect Eric is having an affair with their employee Sherry (Alexandria DeBerry). After kicking Eric out of their shared apartment April meets the rich and mysterious Randall (Eric Balfour), a man whose obsession with clothes may rival her own. Fashionista hangs on a spectacular performance by Amanda Fuller, who gave a similarly impressive turn in director Simon Rumley’s Red, White, and Blue. Rumley has a special talent for portraying pathological behaviors in an unsettlingly immediate way, and here he applies that to April’s erotic obsession with clothing. Fashionista covers a wide range of emotional territory: it’s sexy, funny, heartbreaking, and terrifying by turns. As dark as it gets, though, this is ultimately Rumley’s most optimistic and humane film by a wide margin.

11. I Am Not a Serial Killer (Ireland, dir. Billy O’Brien): Amazon, Google,iTunes, Netflix

John Wayne Cleaver (Max Records) is a high schooler who works at his mother’s funeral home and whose therapist Dr. Neblin (Karl Geary) has diagnosed him as a sociopath. John has a set of rules he follows to prevent him from hurting others, but when a rash of murders strikes the small town where he lives John begins breaking those rules as he launches his own investigation into the killings. He quickly learns that there is something in town much more dangerous than himself. I Am Not a Serial Killer is flat-out amazing, a seemingly effortless mix of mystery, horror, and coming of age stories driven by a pair of fantastic lead performances by Max Records and Christopher Lloyd as John’s elderly neighbor Crowley. It’s often quite funny, and manages to be touching and unsettling without ever tipping too far into any one direction. It also looks beautiful, shot on 16mm film to give it a warm, pleasingly analog grain. Like Julia Ducournau’s Raw, this deserves to be an instant classic of “coming of age” horror.

10. Little Sister (USA, dir. Zach Clark): Amazon, iTunes, Netflix, Vimeo

Colleen (Addison Timlin) is really trying to make a go of becoming a nun in New York, but it’s tough. One day she gets a call from her mother Joani (Ally Sheedy) back home in North Carolina who she hasn’t spoken to since she left for the city, informing her that her brother Jacob (Keith Poulson) has returned from the tour of duty overseas that left him severely burned. She manages to convince The Reverend Mother (Barbara Crampton in a fantastic supporting performance that lets her flex her comedic as well as dramatic chops) to loan her the convent car to go for a brief Halloween visit before Colleen takes her first vows to hopefully make some sort of peace with her damaged family, but when she arrives the situation is much worse than she anticipated. In order to reconnect with her brother and parents, she has to make a kind of return to the person she was before she left home before she can move forward with her new life.

Among the countless pleasures of Little Sister is its sly inversion of the typical movie makeover: Colleen transforms herself from a well-kempt but understated blonde novitiate to a pink-haired, navy-lipsticked, corpse-painted terror. It’s funny, of course, but it’s also really touching—it’s the only way she can reach her brother, trapped in his self-imposed isolation from everyone including Tricia (Kristin Slaysman), his young wife who lives along with him in his parents’ home. While the film primarily focuses on Colleen, writer/director Zach Clark fleshes out the stories of the other characters’ lives in simple but eloquent flourishes: Tricia’s sexual frustrations, Joani’s constant desperate attempts to keep a lid on her own seething anger, Colleen’s old high school friend Emily’s (Molly Plunk) potentially dangerous hobbies (and her long-smoldering crush on Jacob), the Reverend Mother’s vanishing patience for Colleen’s flakiness. Little Sister is a beautifully written, perfectly cast, sweet, funny, and hopeful little film that is also a perfect non-horror Halloween movie.

9. Toni Erdmann (Germany, dir. Maren Ade)

Following the death of his beloved dog Willie, Winfried (Peter Simonischek) decides to visit his successful daughter Ines (Sandra Hüller) to reconnect. But Ines is too busy and/or embarrassed to see him, stressed out from long hours and her own ambitions, so Winfried devises a scheme. He poses as a “life coach” named Toni Erdmann who wears a ridiculous wig and goofy teeth and insinuates himself into Ines’s business life, much to her initial panic and reluctant amusement. Toni Erdmann is utterly unique, a nearly three-hour German comedy/drama that is genuinely hilarious and poignant. Simonischek is great as prankster Winfried/Toni, and the interaction between Toni and Ines’s co-workers and associates is masterfully acted. Sandra Hüller is spectacular, giving Ines a real arc culminating in a touching and funny musical number that is one of the most memorable scenes in any film this year.

8. The Handmaiden (South Korea, dir. Chan-wook Park)

Sook-Hee (Tae-ri Kim) is hired to be the handmaiden of the beautiful but reclusive Lady Hideko (Min-hee Kim), a Japanese woman who has grown up in her uncle’s large manor in Korea. But Sook-Hee is actually working in tandem with con man Count Fujiwara (Jung-woo Ha), who is scheming to marry Hideko and abscond with her father’s vast fortune. Sook-Hee’s job is to help Hideko fall in love with Fujiwara, but the situation becomes even more complicated when Sook-Hee falls in love with Hideko. The Handmaiden is a spectacular return to Korean cinema after Park’s English-language debut Stoker. Adapting Sarah Waters’s novel Fingersmith, director Chan-wook Park has created an intricately designed puzzle box of a film that deftly combines period drama and erotic thriller. It’s also surprisingly funny and unafraid to be swooningly romantic, all shot through with Park’s trademark stylish direction. The cast is brilliant, and the costume and production design is stunningly gorgeous. In a career that has already included more than one certified classic, The Handmaiden stands out as one of Park’s best.

7. Swiss Army Man (USA, dir. Dan Kwan & Daniel Scheinert): Amazon,Google, iTunes

Swiss Army Man was destined to be spectacularly divisive, gleefully displaying its opening title card over the triumphant image of Hank (Paul Dano) riding corpse Manny (Daniel Radcliffe) like a jet ski propelled by his prodigious farts across the open sea. It’s a Sundance legend now, that opening bit sending audience members frantically running for the exits. And while on some level that’s totally understandable, it also means a lot of people have bailed on Swiss Army Man before even realizing what the film actually is: underneath all the fart, vomit, and boner jokes, there’s a touching but ultimately bleak meditation on father/son relationships and male friendship, as well as a savage satire of the kind of quirky “sensitive guy” indie movie Swiss Army Man feigns itself to be for a large part of its running time.

Of course, what makes the film such a surgically effective piece of satire is that it uses all the same tools as the films it critiques, and uses them in expert fashion. Paul Dano starred in Little Miss Sunshine, the prototypical modern “quirky Sundance movie”; his casting here can not be coincidental. The acapella score by Andy Hull and Robert McDowell is twee and vibrant, and often partially performed by the characters in the action of the film. A large part of the story relies on Hank’s artistic abilities to craft elaborate life-size stage settings out of garbage he finds in the forest. The look and tone of the film, as well as the way Hank is written, codes him as what should be a “Manic Pixie Dream Guy,” which allows for filmmakers Daniels to illustrate the impossibility of the very concept. And yet the performances of Dano and Radcliffe are so earnest and committed, their respect and affection for each other so apparent, that it’s virtually impossible not to be charmed and touched by their friendship. This is a lot of plates for any film to keep spinning, but Swiss Army Man does it admirably before deploying the crashing of some of those plates to deliver a satirical nuclear payload right past your best defenses.

6. Moonlight (USA, dir. Barry Jenkins)

I’m not sure if I saw Moonlight under the best or worst possible circumstances, because I watched it early in the day on November 8th. I left the theater dazzled and a little giddy, then went home and watched as Donald Trump won the election for President of the United States of America. It was a dizzying drop from the high of watching this film to the plunge of despair as the polls came in from around the country. A friend of mine wrote a song about the impending end of campaign fatigue and I drunkenly slapped together a video for it, and then I stayed up late enough to confirm my worst fears about humanity and finally went to bed. I didn’t think about Moonlight for a while after that day, because there was a lot of other stuff to think about. I hit a point where I honestly wondered why I bother watching so many movies or writing about them. What good does any of that do in the world we now live in?

It wasn’t until after I saw La La Land that my brain started to dig through the debris that had collapsed on top of my viewing of Moonlight, to exhume that experience and dust it off for closer examination. This is not to say that both of these films are entirely “happy” (more on that later), but La La Land has an infectious Technicolor immediacy that provides many moments of fleeting bliss. Moonlight, on the other hand, is defined by moments of totally unexpected joy. And not only from its beautiful, masterful direction, cinematography, and sound design, but from a deep satisfaction born of watching actors whose roles could easily be faceless stock characters given the kind of inner life they almost never get in any film. These performers imbue their characters with heart and soul, relying largely on expert nuance of physical cues and expression when words fail (which is often).

All of which is to say that watching Moonlight gave me a feeling that I rarely encounter: optimism. On so many different levels it’s difficult to properly express it. And after that small flame of hope had been buried under a mountain of horrible shit, I came back to dig it out and found it still faintly flickering. It would have made my list if it had somehow done that while being a complete disaster as a film, but it did it in extraordinarily assured style. It should be required viewing for anyone who has spent much of the past few months trying to make sense of the world and decide whether cinema can actually matter. Here is a powerful argument that it can, and it does, and probably always will regardless of what new forms it may eventually take.

5. Judge Archer (China, dir. Haofeng Xu): Amazon, Google, iTunes

Following a brutal attack on his sister by powerful men in their village, a young man (Yang Song) is sent nameless over the wall of the monastery where they took refuge. He is commanded to take the first words he hears as his new name and start a new life, but somewhat unfortunately, those words are “Judge Archer.” This is the title of a man who acts as arbiter between martial arts schools settling their disputes, and who is frequently a target of revenge and potential assassination for his dispensation of justice. The current Judge Archer takes the young man under his wing and trains him as a replacement. Years later this new Judge Archer finds himself embroiled in a complicated web of political and personal conflicts between a number of dangerous parties.

Haofeng Xu’s debut feature The Sword Identity is one of the best and most unusual martial arts films in recent memory, something like what one might imagine the Coen Brothers might do with this type of film. Judge Archer, originally produced in 2012 and not seen since a handful of festival screenings in 2012–2013, received its North American premiere at Fantasia after Xu’s third film The Final Master had already received a limited theatrical release in the States. It’s disappointing but not surprising that the film’s Chinese studio wasn’t sure what to do with it: like The Sword Identity, Judge Archer is a film that gleefully confounds expectations of what constitutes a “martial arts” movie. It’s masterfully directed, acted, choreographed, and edited, with its placid surface and energetic bursts of action seemingly prefiguring Hsiao-Hsien Hou’s approach to the form in The Assassin. Unlike that film, though, Judge Archer is lightened by Xu’s odd sense of humor, giving it a much less self-serious tone than many films in this genre. Here’s hoping its warm reception at Fantasia coupled with the release of The Final Master will help gain Xu the reputation he deserves as one of the most intriguing artists working in international cinema.

4. La La Land (USA, dir. Damien Chazelle)

This was a great year for gauntlet-throwing opening scenes: Swiss Army Man’s lead-up to its title card may have been the funniest, and I Am the Pretty Thing That Lives in the House is untouchable in its sheer audacity, but Damien Chazelle’s La La Land has the most vivacious and dangerous. How the hell do you keep up the kind of pace such a show-stopping number sets before the title of the movie even appears on the screen? As it turns out, you don’t — that opening gambit is not (as it initially appears) a lead-in to a sprawling Altmanesque ensemble character study, but is instead a frantically sketched shorthand look at a world in which every character is in their own personal movie about trying to Make It in Show Business. It gives the audience a lot of information right up front, although that may not be apparent to the viewer until much later. “Another Day of Sun” tells us that La La Land is about characters who work hard and make difficult choices and are romantic and unrealistic and possibly delusional about their chances of winning the metaphorical lottery and achieving their dreams.

But that’s the thing about the lottery, right? Somebody has to win eventually. La La Land centers on characters who have big dreams: Mia (Emma Stone) is a struggling actress with talent and determination who wants to break into the business, but she’s drowning in a sea of other women going through the exact same thing. Sebastian (Ryan Gosling) is a charming but annoyingly pedantic jazz “purist” who wants to “save jazz” by buying a legendary club that has been blasphemously turned into a samba tapas restaurant and changing it back to exactly what it was before the new owners came in. Their parallel paths cross over the course of a year as they meet, fall in love, and encourage each other to make their dreams reality. None of this is uncharted territory, of course, but La La Land applies the cinematic language of the big Hollywood Musical (down to the “Filmed in Cinemascope” title card right before the film opens) to a story more down-to-Earth and bittersweet than the familiar “rags to riches” trope it could easily have fulfilled.

That’s what makes La La Land so compelling in the end: it has more moments of pure cinematic joy than any other film released this year, but it’s not a “feel good” movie. Chazelle stages much of the dance numbers in long, sweeping takes with the camera diving in for playful close-ups and pulling back for dizzying high, wide angles while the music pulls everything forward like a rushing current. La La Land is unafraid of being nakedly earnest in a way that risks embarrassment, particularly in the pivotal “Planetarium” sequence that marks its furthest point out into gentle surrealism. This can feel somewhat jarring because hardly anybody here is a pro singer or dancer, but that’s kind of the point — Chazelle shows us these everyday characters (as much as Ryan Gosling and Emma Stone can possibly be “everyday”) experiencing emotion as filtered through classic entertainment. It would feel less emotionally authentic if they suddenly broke out in technically dazzling, impossibly proficient choreography. There’s no way in hell most viewers could do most of what they do, but it’s easier to imagine they could than to think they could ever touch Ginger Rogers or Fred Astaire.

And still, what makes La La Land stick so unwaveringly in the mind is not the earnest joy, but its complex characterizations and realistic approach to success. Chazelle’s 2014 film Whiplash also told the story of a character dedicated to a dream of artistic greatness, but in that case it’s ultimately a kind of modern horror-film take on The Red Shoes. In La La Land, neither character has to give up their own humanity to get what they want, but they still have to make painful sacrifices and difficult choices. Even in the film’s beautiful epilogue is buried the impossibility of these characters having everything exactly the way they wanted it — notice from whose viewpoint we see that whole “what could have been” sequence. As romantic and perfect as it seems, there’s no way it could have ever worked how it’s imagined. Gosling and Stone have such powerful chemistry that the highs here are ecstatic, and the lows are devastating. La La Land gives us some brief romantic escapism into an idealized world before lowering the boom, but it’s not the end of the world. And sometimes that feels like the worst part.

3. The Arbalest (USA, dir. Adam Pinney): Amazon, Google, iTunes

In 1968, inventor Foster Kalt (Mike Brune) presented at the biggest toy convention in the world and became one of the richest men alive from “The Kalt Cube.” Ten years later, an investigative journalist and her crew join Foster at his isolated home in the woods for his first interview in four years and the unveiling of his new invention. But Foster wanders away, still wearing his lapel mic, and begins spinning the tale of how the mysterious Sylvia (Tallie Medel) has figured into his life. The Arbalest is the debut feature from Adam Pinney, who worked as cinematographer and editor on the horror/comedy Blood Car (a cult classic in waiting) as well as shooting Joe Swanberg’s 24 Exposures and the Adult Swim short “Too Many Cooks.”

While those previous titles may give a rough idea of where Pinney’s film lands, it’s even more perplexing than they might suggest. Mike Brune, star of Blood Car, is very funny as Kalt, but the show really belongs to Tallie Medel as Sylvia. She’s hilarious and compelling, giving the film yet another unexpected facet in her deadpan performance as a woman whose apathy towards Foster is nearly matched by his dangerous obsession with her. The film looks gorgeous, and the period design and costuming are excellent, as is the appropriately dreamy score. It’s a wildly absurdist take on Citizen Kane that is utterly unlike anything else out there.

Recently divorced Mel (Maryann Plunkett) lands in the hospital following a “nervous breakdown.” While Mel spends time in the hospital psych ward, her daughters Connie (Jennifer Lafleur) and Casey (Eilis Cahill) try to figure out what to do. Connie, a successful businesswoman and mother, keeps up a strong façade but is dealing with some potentially serious legal problems at work. Younger sister Casey is still trying to get her shit together, and in the meantime works from home doing sex cam shows. MAD is a brilliant dramatic showcase for its three leads that also happens to be wickedly funny. All three women are amazing in their roles, and their characters are sharply written by debut feature director Robert G. Putka. He and his cast clearly understand that those who we love the most are capable of cutting us down most effectively, and play that out in spectacular fashion. It’s hilarious but it’s also deeply poignant, and deals with aspects of life and characters that are rarely seen in American movies of any type. It’s almost unbelievable that this is Putka’s first feature, and I can’t wait to see where he goes from here.

Anna Biller, in addition to being a filmmaker, is a capital-A Artist of the first rank. Her fingerprints are on almost literally everything in her films: she writes, directs, edits, produces, composes and performs music, designs sets and costumes, etc. etc. etc. She exerts a level of singular artistic vision and control over what makes it to the screen that would have made Stanley Kubrick blush in shamed admiration and possibly even impressed Andy Milligan. Like Matthew Barney’s film work, her films are not “just” the final narrative product that ends up projected on the screen; the films are also a document of every piece of clothing, every painting on the walls, every elaborate hand-sewn rug, every thing that was created to populate that film’s specific world. But where Barney is interested in arcane and impenetrable symbol systems and outrageous performances of extreme physical behavior, Biller’s work is firmly rooted in narrative convention. She uses another type of symbol system, cinematic languages and storytelling tools largely considered to be obsolete. This tends to cause many viewers to confuse her films for simple pastiche or parody of bygone styles of filmmaking, and anyone who makes this mistake should really get caught up on reading everything on Biller’s fascinating and fiercely intelligent blogASAP.

The Love Witch uses the form and structure of a 1960s/1970s exploitation film but is designed from the ground up as a commentary on a number of issues in modern society. It’s an important distinction to make that Biller uses “obsolete” approaches to comment on the state of the world as she sees it now. Anyone who saw her 2007 feature Viva and assumed it was more or less equally valid as a social commentary about gender relations in 2007 as, say, Russ Meyer’s Vixen! (1968) has a fundamental misunderstanding of the fact that any work of art is inherently on some level about the era in which it is made. The same goes with The Love Witch, although this time Biller takes the extra step of eschewing the “period piece” approach of her previous work by setting this film in modern day. The costumes, hair, makeup, and set designs may all signify the 1970s, but those things coexist in the world in which heroine Elaine (Samantha Robinson in a performance that should by all rights instantly make her an huge star) lives with modern cars and cell phones. The juxtaposition is a way for Biller to share with the audience the way Elaine sees her world instead of recreating a different era in order to comment on our own, and the resulting effect is intoxicating.

Honestly, pretty much everything about The Love Witch is intoxicating. There’s the unbelievable production and costume design, of course, making every frame of the movie worth staring at for hours on end to pick out its endlessly intricate detail. The perfectly stylized performances, the recontextualization of haunting Ennio Morricone soundtrack cues, the exacting replication of the unhurried pace of the films of the era The Love Witch evokes. And this is all before even taking into consideration the fact that the film was shot on 35mm film by cinematographer M. David Mullen(Jennifer’s Body, Shadowboxer, Northfork) and painstakingly edited by Biller herself on a 35mm editing table. Thank the Gods of Cinema for Oscilloscope’s decision to distribute the film theatrically via 35mm prints! As with the 35mm exhibitions of Inherent Vice during its theatrical run, watching The Love Witch projected from a print is the closest to a religious experience some hardcore cinephiles are ever likely to get. It’s difficult to overstate the difference it makes to see a film designed and shot for 35mm film projected in that format versus a digital presentation. The texture of the film and the wear from projection become a part of the film, make of it something new every time.

The Love Witch is a vital reminder of what is possible in cinema, and that there are still endless avenues left to explore for adventurous filmmakers willing to not just pay homage to film history, but to mine it for new ways to look at our world as it is now. It’s a brilliant, dazzling hall of mirrors that I am always happy to dive into again. I hope it’s not another decade before we see another feature from Anna Biller, but The Love Witch proved beyond the shadow of any possible doubt that even if it is, it will be well worth the wait.

- [CINEPOCALYPSE 2017] FIVE FILMS YOU CAN’T MISS AT CINEPOCALYPSE! - October 31, 2017

- Hop into Jason’s Ride for a Look at the Wild World of Vansploitation! - August 11, 2014

Tags: Addison Timlin, Ally Sheedy, Amanda Fuller, Amy Adams, Anna Biller, Anne Hathaway, Annette O’Toole, Barbara Crampton, Barry Jenkins, Best Of 2016, Canada, Chan-wook Park, China, Christopher Lloyd, Damien Chazelle, Dan Stevens, Daniel Radcliffe, Denis Villeneuve, Emma Stone, Eric Balfour, Ethan Embry, Fantastic Fest, Germany, Ireland, Jason Coffman, Jason Sudeikis, Jeremy Renner, Matthew Barney, Max Records, Nacho Vigalondo, Norman Mailer, Paul Dano, Robert G. Putka, Ryan Gosling, Samantha Robinson, South Korea, Trey Edward Shults, Uganda

No Comments