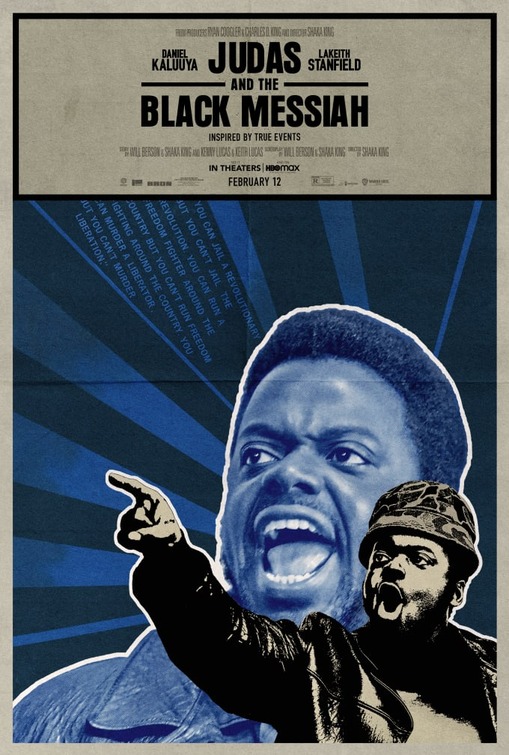

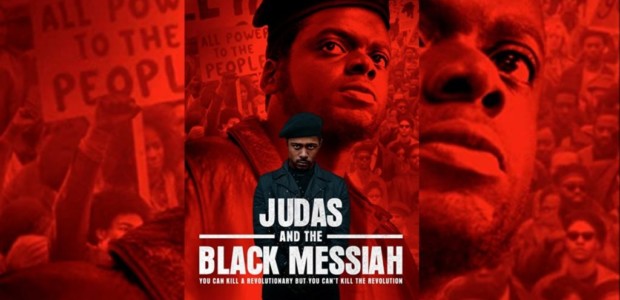

Shaka King is a visionary director and storyteller, and he brings all of his weight, energy, and narrative eye to his prescient biopic of murdered Chicago Black Panther activist and founder of the Chicago Rainbow Coalition Fred Hampton (Daniel Kaluuya) and the federal plant, William O’Neal (LaKeith Stanfield), who betrayed him: JUDAS AND THE BLACK MESSIAH.

Kaluuya (GET OUT, BLACK PANTHER) delivers an Oscar-worthy performance, stepping into the shoes of Hampton with aplomb. Anyone can repeat the words of a dead man — the biopic is an entire genre, after all — but it’s quite another to embody and bring to life the ethos, charisma, and passion that made Fred Hampton the force of community and social justice he was: a man that almost united the most segregated city in the world and a force that put fear into the FBI and the CPD, to the extent that he was seen as better off dead than alive. At the times where Hampton’s real voice is heard onscreen, it becomes even more clear how much effort and care was put into capturing his cadence and the impact behind his words, the mixture of which can almost make one forget that they were coming from a 21-year-old and not someone twice or thrice his age.

Likewise, Stanfield does a lot of work portraying the conflicted existence of a man who betrayed someone who trusted him for the sake of money and a get out of jail free card while simultaneously being used and exploited by the exact kind of politically backed white racists that Hampton and the Black Panther Party at large were trying to defend their communities against. He’s someone who watches as all of the impoverished people in the city of Chicago start uniting against a system that puppeted him on strings only to cut him loose when the blood money was paid, and who suffers the lifelong consequences accrued as a result.

Overall, King captures the environment of 1960s Chicago with all the fidelity and respect it deserves, for good and for ill. It’s so easy to fall into the habit of showcasing the West side of Chicago in particular, and the minority/ impoverished neighborhoods at large as a grey-toned pit of despair and decay, but King allows the vibrance, music, and soul of the communities the Black Panther Party, Rainbow Party, et. al. maneuvered in and lived in until the shuttering of the Illinois chapter years after Hampton’s murder. Likewise, the film does not shy away from showcasing the Chicago Police Department of the 60s as the corrupt and bigoted force they were proven to be at the time (and are still considered by many to be today), with their ranking as one of the top three most violent and corrupt police forces in the United States (Los Angeles and New York close statistical bedfellows).

This, no doubt, will ruffle a lot of feathers in the new era of the Black Lives Matter movement and the blowback from police that ensued as a result of the increased calls for accountability and transparency in their dealings both present and past. However, these are feathers that have to be ruffled: a sanitized portrayal of The Two Chicagos would be a betrayal not only of the true story that begs to be told as widely as possible, but also of the people of Chicago still living with systematic inequality, disproportionate poverty, and outside stereotyping of the city as a place of violence and chaos rather than the social justice and equality-minded community it can be when it’s allowed to be — when those voices working for it to be so aren’t continually snuffed out. Equally as important, King emphasizes the intersectional activism that was fostered here in the 1960s through Black people, Latinos, and “white trash” residents (among others) joining together against the shared roadblocks and discriminatory forces their communities faced from government apathy and capitalistic greed. As Hampton said, the race of water in an America that was burning around them instead of communities in fighting over who is and is not a racial, sexual, or economic outsider. It’s a message and ideal perhaps more important now than ever with the broad social damage done by COVID, neo-facism, the dissolving of the middle class, and the smothering of those in poverty.

One could discuss some potential negatives in the film: the sometimes-lopsided focus of the narrative and the occasional issues of pacing in the more intimate portions of the characters’ lives, but honestly, for a film like this, that almost seems beside the point.

JUDAS AND THE BLACK MESSIAH releases on VOD on February 12th, 2021 and is now playing on HBO Max, and everyone should watch it.

Tags: Black Panthers, BLM, Chicago, Craig Harris, Daniel Kaluuya, Dominique Fishback, Fred Hampton, History, Jermaine Fowler, Jesse Plemons, Keith Lucas, Kenny Lucas, LaKeith Stanfield, Lil Rel Howery, Mark Isham, martin sheen, politics, Ryan Coogler, Sean Bobbitt, Shaka King, Sundance, Sundance Film Festival, Will Berson

No Comments