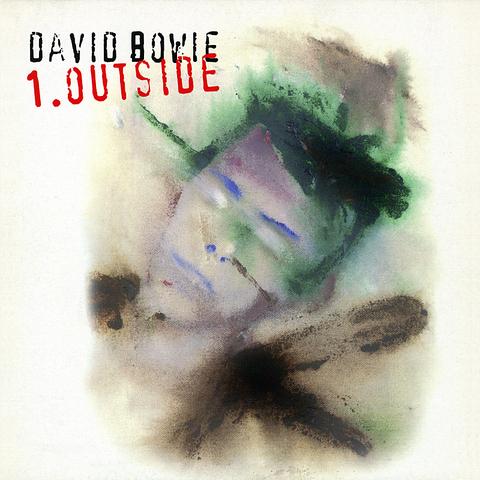

Cover art is Head of DB by David Bowie

Nihilism was one of David Bowie’s favorite playthings. His Diamond Dogs album was about a post-apocalyptic place, Hunger City, and was inspired by his failed 1984 musical. The tale of Ziggy Stardust begins with him telling us that we have five years left to live and ends with him being killed by his fans. Nihilism even reaches back to his first, self-titled album in 1967. Please Mr. Gravedigger, the closer, was about someone confessing to the title character, who’s also a graverobber, that they killed the little girl he’s burying in the rain. And that they’re burying a grave for him, in case he ever feels confessional. Bowie toyed with nihilism even as his Blackstar burned bright, though it never reached such a gleeful pitch as when he went Outside.

1.Outside (which, for the remainder of the article, will be referred to as just Outside) was Bowie’s reaction to a few things near the end of last millennium. Sex, violence, and death were all the rage at the album’s conception, and he focused on the artistic trend of (self-)mutilation, also known as “ritual art” and “performance art”… as any Hellraiser fan could tell you. He was drawn to the (self-)mutilation-as-art community because it was a trend moreso than the art it provided. He felt that ritual art was a faint echo of Paganism and that its creations were sacrifices to the gods for a better millennium. He also said that absolutes were antiquated, chaos was modern, and artists were trying to make sense of it. Elaborating, “Because possibly the Judeo-Christian ethic doesn’t actually embrace our feelings and our fears of sex and violence that it really ends up in the area of popular culture to assimilate those fears and terms.” His only rule in making what would become Outside was to stay outside of the musical mainstream, which was one of many reasons why he chose to work again with Brian Eno.

In the late-’70s, Bowie shipped off to Berlin with Iggy Pop to get their lives together. Bowie was living in LA at the height of his Thin White Duke and drug abuse eras. He lived on a diet of green peppers, milk, and narcotics while slowly convincing himself that Satanists were coming for him. You get a taste of his paranoia in the title track of Station to Station. Eventually, he decided to make an album with Eno after loving his solo albums. It was a mutual admiration society because Eno was a rather large fan of Station to Station. They turned what was Bowie’s unused score for THE MAN WHO FELL TO EARTH into Low, the first part of the Berlin Trilogy. They completed the triptych with “Heroes” and Lodger, then went their separate ways during the ’80s. The seeds of working again were planted at Bowie’s wedding in 1992. Bowie created music for it that ended up becoming a third of his Black Tie White Noise album, and Eno said that it sounded a bit like what he was working on. They talked off and on about potential projects until everything clicked in March of 1994.

Before they started work on Outside, a mutual friend, André Heller, suggested that they visit the Maria Gugging Psychiatric Clinic, near Vienna. All the inmates there were visual artists who created outsider art, and Heller felt that the two could be inspired somehow. Bowie liked the sense of exploration and the lack of self-judgment the inmates had, which became an atmosphere for the album. He didn’t want to work on melodies because he felt that he was naturally inclined to and wanted whatever melodies came to bump against that instead of becoming a tune factory “where you walk out of the building singing the set.” He was more interested in creating something with music instead of creating songs.

In the rehearsal space, Bowie and the band were in the hands of Eno’s… unique inspirations. Eno wasn’t a classically-trained musician and didn’t know much about music notes, so the way he created was to give himself prompts and find songs through them. He wanted Bowie’s songs to come from improvisation, but wasn’t a fan of regular jam sessions. “When you ask musicians to jam, the common ground will always be the bloody Blues.” So his plan for creating music with Bowie was making tasks that set the mood for the rest of the day, then refine in the studio. An example: “You are the disgruntled ex-member of a South African Rock band. Play the notes you were not allowed to play.” They started with a three-hour improv session, with Bowie acting as a storyteller and characters grew from that. In December of that year, he was asked to write a ten-day diary about his life, which he turned into a 15-year diary about Nathan Adler, one of the characters from improv. He then combined the diary and the music, so the concept of the album grew along with the improvs instead of being their cause.

Bowie evolved his cut-up technique for lyrics from the 70’s by co-designing a program, the Verbasizer. To cut-up means turning a few sentences into puzzle pieces with scissors, then making new sentences. He borrowed the technique from William S. Burroughs because he loved how it unlocked creative avenues he wouldn’t have found if he tried thinking linearly. The Verbasizer cut out (ha) the time it’d take normally and made things more erratic than originally thought possible. Going deeper, “The subject of the album may be the story of Nathan Adler. The content is actually the texture of 1995. The story is the skeleton, and the flesh and blood are the feeling of what it’s like to be around in 1995.” What developed was a tale of artists who moved from self-mutilation as performance art to mutilating others. Nathan Adler, an art detective, was hired to find the ring of artists who murder to get body parts for their art because of the death of a 14-year-old girl, Baby Grace Blue. The suspects were Leon Blank, convicted for plagurising without a license, Ramona A. Stone, a No-Future priestess of the Caucasian Suicide Temple, and Algeria Touchshriek, an art-drug and DNA-print dealer. When Bowie, Eno, and the band were finished, they had a new album… Leon.

Leon is the Live Santa Monica ’72 of the 90’s for Bowie fans. Largely regarded by many die-hard fans as his best live album, Live Santa Monica ’72 wasn’t supposed to exist. A radio station broadcast the concert and a fan recorded it with his stereo, then made bootleg vinyls. It was the prize of any serious collector and was as easy to find as a happy ending in a Lars von Trier film. Bowie eventually allowed the recording to have an official release in 2008. Leon was, for lack of a better term, a demo for Outside. Or rather, it ended up that way because record companies wanted nothing to do with the album. Leon is great, but it’s by no means a mainstream affair. You wouldn’t hear it in a waiting room. You’d be more likely to hear it in a nightclub where everyone sits on cushions and wooden crates, imbibing various things while all the screens play clips of “Metropolis”, “Haxan”, and the art of Joel-Peter Witkin. So Bowie and Eno went back to the studio and overproduced what was close to being Outside. They overproduced with Leon, too. Mike Garson, pianist for the album and creator of the manic solo in Aladdin Sane‘s title track, said that there was enough material from the March ’94 sessions for at least ten albums. Bowie and Eno whittled Outside down to a triple-album, but no label wanted it unless they made it a single. They did, and it ended up being Bowie’s longest. The album’s loud, furious, and fractured, just like the final years of the millennium. Outside’s first music video, for Hearts Filthy Lesson, fully embraced the ritual art inspirations that got the gory story started. When asked about the song’s title, “I think the filthy lesson of the heart is […] when you really understand that you die.” There was talk over the years to make at least two companion albums: 2. Contamination and an operatic Inside. Neither happened.

Why 1. Outside? Bowie wanted to make a series of albums, one a year, leading up to the year 2000. He wanted to catch the spirit of each year as it passed and end up with a musical and textual diary of the last five years. Instead, he had just The Diary of Nathan Adler, Or the Art-Ritual Murder of Baby Grace Blue. He wanted to take all the albums of the cycle and create an eight-hour piece for the stage to maybe play at the Brooklyn Academy in 2000. Something like Robert Wilson or Weill-era Bertolt Brecht would’ve made. Instead, he had just “a non-linear Gothic Drama Hyper-cycle”. Bowie, Eno, and Heller wanted to create an in-world film, but the money-people got too involved. Then Bowie toured with Nine Inch Nails in the US. Anyone wondering why those two would be together need only listen to NIN’s A Warm Place and Bowie’s Crystal Japan. During the tour, NIN would play their songs, then Bowie would come onstage and they’d play each other’s songs, then Bowie would play his songs solo. The tour wouldn’t be the last time they worked together, though. Trent Reznor would co-star in the video for Bowie’s I’m Afraid of Americans, off of his next album, Earthling, as well as do a few remixes of the song. When Reznor was hired by David Lynch to produce the soundtrack for LOST HIGHWAY, because of his work on the one for NATURAL BORN KILLERS, Reznor suggested that they use Bowie’s I’m Deranged. That song opened and closed the film.

Now go and give it a listen.

Tags: Brian Eno, David Bowie, Iggy Pop, music

No Comments