Once upon a time, in a state far, far away, a young boy fell in love with a science fiction movie. Years later, he would find out that the science fiction movie didn’t really love him back. And years later yet, the boy would decide to give the science fiction movie another chance.

Ten years sober and I choose now of all times to relapse.

At the age of fourteen, I had copied over the entire NPR STAR WARS radio drama from library cassettes, read through the extended universe STAR WARS fiction, and been quoted in my local newspaper as one of the people who had stood in line all day for STAR WARS: EPISODE I—THE PHANTOM MENACE. At the age of fifteen, after coming to terms with George Lucas’s new vision for the franchise, I put down my collection. In less than a year, I finally admitted that EPISODE I and the special-edition releases had deeply affected my fandom. I fell in love with the STAR WARS franchise as a kid, but the high-school version of me was drawn to the flawed humanity of the characters, not service droids running a Three Stooges routine during a podrace.

For a long time, I was bitter about the franchise. I argued with people who tried to defend the prequels and angrily explained the aspects of the films that contradicted the extended universe canon approved by Lucasfilm. I still enjoyed the idea of STAR WARS, but I hated Lucas for his inability to see his own shortcomings. Eventually, this anger faded into a kind of bemused acceptance. Although I had no interest in seeing more STAR WARS movies, I would always remember the original trilogy and the positive effect they had on me as a kid. They taught me to love film and to read for fun; like it or not, STAR WARS helped shape me into the person I am today, and fighting that would only darken some fond childhood memories.

With that in mind, I’ve vowed to be positive about the new movies. Consider it an exercise in nostalgia, a throwback to a time when I thought that the STAR WARS universe would only get bigger and more interesting with each subsequent entry. In preparing for this piece, I put myself through all three prequels in a twenty-four-hour period—films I hadn’t watched since they were originally released in theaters—and I surprised myself by finding aspects of Lucas’s newer trilogy that are worth building on. One could choose any number of things to focus on in the STAR WARS films, but I’ve selected a few things that stood out to me.

This is my STAR WARS article. There are many like it, but this one is mine.

This Deal is Getting Worse All the Time!

One of the glaring flaws of the STAR WARS prequels is their insistence on introducing—or reintroducing, as the case may be—every major character and alien from the STAR WARS universe. R2-D2 and C-3PO play major roles in all three films; the origin story of Boba Fett is disappointingly mundane; Chewbacca and Yoda are close friends who never acknowledge their respective existences in THE EMPIRE STRIKES BACK or RETURN OF THE JEDI. By wedging characters from the original trilogy into his prequels, Lucas is demonstrating that it is not their actions that make them importance but rather their importance that drives their actions. We spend time on Naboo because it is the home world of Padmé, who is in turn the mother of Luke and Leia. Once the romance between Padmé and Anakin begins, the political importance of Naboo ceases to exist, and Padmé’s political importance wanes.

Fans are understandably wary of seeing too many familiar faces in the continuation of the STAR WARS universe. As production photos of Tatooine and the Millennium Falcon flood the Internet, fans and non-fans alike openly wonder if the franchise will repeat Lucas’s same mistakes in recycling material for his prequels. The previous entry in the STAR TREK series does nothing to encourage our sense of hope; Benedict Cumberbatch’s character of Khan existed almost entirely as an intertextual item. Abrams and his writers seemed content to let the audience fill in all the blanks rather than organically build the tension between Khan and Kirk.

These are all valid reasons for concern; still, that does not prevent me from hoping for the return of the Galactic Empire in the sequels. One of the reoccurring themes of the extended universe novels was that not all Imperial units surrendered after the battle of Endor. Some squadrons retreated to remote systems and began the same guerrilla-warfare tactics that the Rebellion used in the original films; others—having experienced only the stability that the Empire provided—openly rebelled against the new governing body. If the STAR WARS franchise is to be redeemed in the eyes of critics and fans alike, then a return to the Empire as the primary villain would provide both a natural continuation of the events of the original trilogy as well as a thematic bookend for the nine-film series.

And while I may have my heart set on a variant of one character in particular, I would settle for any depiction of the rebuilding process that attempts to do more than simply dump exposition on us during the opening crawl. Should J. J. Abrams find the right balance for the inclusion of politics in the series, he would also have an opportunity to refine the commentary on American politics he attempted in 2013’s STAR TREK INTO DARKNESS. A struggling New Republic would go a long way toward showing the difference between winning a war and building something sustainable once the war is over.

Hokey Religions and Ancient Weapons…

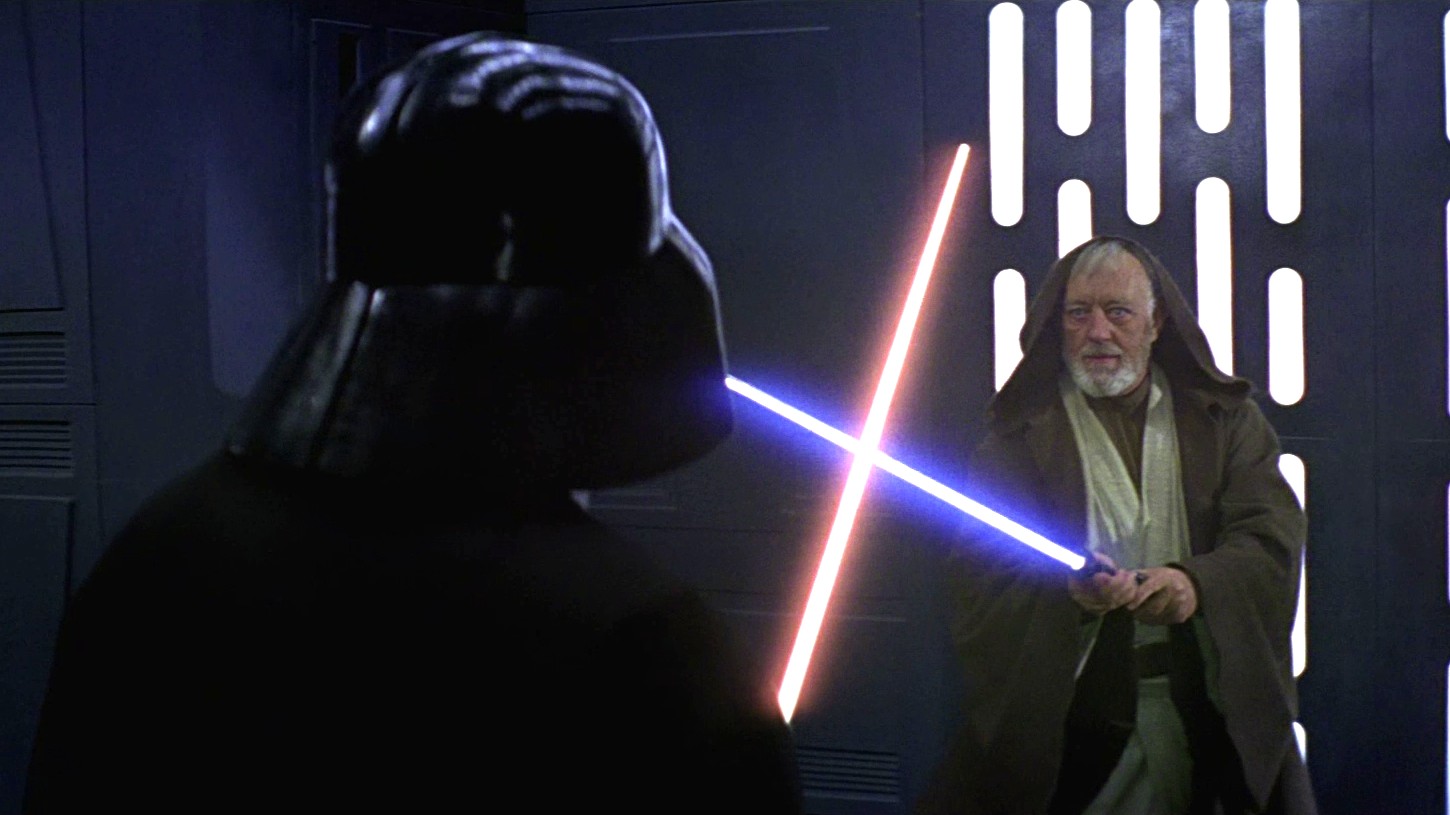

The prequels are an excellent demonstration of both the strengths and weaknesses of the lightsaber as a cinematic weapon. In wide shots with dozens of characters fighting, a Jedi’s lightsaber allows audiences to track the fight choreography—or the animated sequences of combat—and see how combat ebbs and flows around the central characters. However, when Lucas and his team closed in on two or three characters in combat, the fight choreography fell apart. Actors hold their props up at ninety-degree angles to incoming blows; perhaps to disguise the repetitive nature of his action sequences, Lucas often shot the sequences on moving platforms or against a changing background to vary the experience on the screen. Worse yet, the characters in STAR WARS spent more time flipping through the air than they did actually swinging their lightsabers.

The aesthetics of fight choreography have changed over the past decade. American filmmakers have stepped back from the visual cue of fencing—and the showmanship contained therein—and drawn on martial arts instead. Stamina has replaced agility as the impressive physical characteristic onscreen; audiences are more impressed by Dae-su Oh and his hammer or Rama and his baton than they are with Ray Park and his leaps. We have also learned to weigh our fight scenes on the merits of their stillness rather than their periods of frantic energy. How fighters recover from exhaustion says more about their ability than anything else.

Endurance over style, stillness over movement; these things are not without precedence in the STAR WARS universe. For all the fight sequences in RETURN OF THE JEDI, I most vividly remember the shot which Luke loses control, hammering his blade down again and again on the prone figure of Vader. And while I remembered being impressed by the final lightsaber fight in THE PHANTOM MENACE, the best beat in the film is where the shields come up and each character spends a quiet moment preparing for the next fight sequence. One beautiful moment of calm amid the chaos and confusion of the CGI battles.

Do not simply copy the choreography from Gareth Edwards films; find ways to make lightsaber duels tense again. Vary the choreography, emphasize the importance of pace and stamina. Avoid the use of platforms from REVENGE OF THE SITH and STAR TREK INTO DARKNESS, and allow the action to unfold against a relatively static background. Emphasize the importance of concentration. And whenever possible, keep both actors’ feet firmly planted on the ground. Just because a Jedi can bounce around during a lightsaber fight doesn’t mean your audience won’t laugh at that choice. By its very nature, the force is more closely connected to mental fortitude than physical acumen. It’s time to exhaust our Jedi again.

A Jedi Craves Not These Things

And speaking of Jedi: who needs ‘em?

Obviously, any continuation of the original trilogy will explore the connection that Luke and Leia have with the force. Still, if Abrams and Lawrence Kasdan are to expand the STAR WARS universe, the urge to appoint Luke Skywalker as head of a galactic academy for Jedi will be a tempting jumping-off point for future stories. However, the current landscape of blockbuster films has depleted our appetite for meta-humans. The Marvel Cinematic Universe has spent the past several summers putting the planet in danger and allowing their superheroes to save it again. Even the most ardent fans of Marvel can be subject to superhero fatigue. When each fight is between only superhumans, the role and importance of the regular human element is at best downplayed and at worst downright forgotten. One man with a lightsaber against an army is interesting; two armies with lightsabers has no interest.

Furthermore, most fans of the original trilogy relate more to the human characters than those with supernatural abilities. I never wanted to be Luke Skywalker as a child; I wanted to be Han Solo, someone who succeeded due to charm and guile. Lucas attempted to develop a power structure in the prequels whereby the Jedi served the people; somehow, that message became subverted by the struggle between a small group of force users. The character who impresses the most in REVENGE OF THE SITH is not Yoda or Obi-Wan Kenobi, but rather Jimmy Smits’s Bail Organa, a politician who risks his life and status to harbor Jedi fugitives after the genocide of their people.

With trillions of average citizens in the galaxy and only a handful of force-sensitive people, the emphasis in STAR WARS stories should always be to find the human element above the superhuman one. After all, possibilities for planets and races in the STAR WARS universe are practically endless. You can flesh out a race featured in one of the other films; move away from fringe planets and explore the core planets in the New Republic; spend time on the black market and explore the galaxy’s booming bounty hunter industry. Put simply, if you cannot find a way to tell a story in the STAR WARS universe without Jedi, then perhaps you have no business writing for this franchise in the first place.

— MATTHEW MONAGLE.

- [THE BIG QUESTION] WHAT’S YOUR FAVORITE FEMALE ENSEMBLE IN MOVIES? - July 22, 2016

- [IN THEATERS NOW] THE BOY (2016) - January 24, 2016

- Cult Movie Mania Releases Lucio Fulci Limited Edition VHS Sets - January 5, 2016

Tags: George Lucas, J.J. Abrams, Jimmy Smits, Lawrence Kasdan, Opinions, star wars

No Comments