With BLACKkKLANSMAN, Spike Lee is obviously concerned with depicting one highly unusual chapter in American history; however, he’s also well aware that it’s just that: a brief chapter in a very long, appallingly sordid book detailing the country’s racist past, present, and future. Arguably, he’s subtly even more concerned with tracing the thread of bigotry woven into the fabric of America, specifically noting the role mass media has played in pulling that thread. It just so happens that he’s also found one hell of an entertaining entry point to explore it, a notion that becomes increasingly intriguing in its implications as the film unfolds.

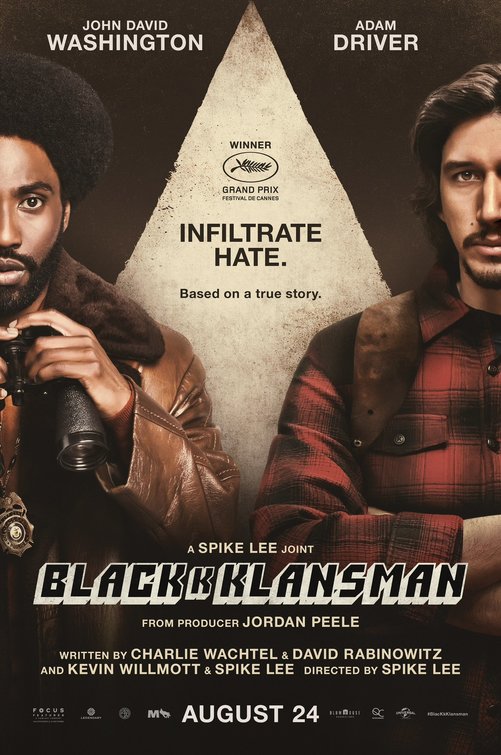

Based on police officer Ron Stallworth’s biography, BLACKkKLANSMANrecounts his days as a rookie cop (portrayed here by John David Washington) on the Colorado Springs police force in the early ’70s. Despite the force’s insistence that “minorities are encouraged to apply,” his status as the department’s first African-American member quickly becomes an elephant in the room. Stuck doing thankless grunt work—often at the behest of the most outwardly racist cop on the force — Stallworth urges his superiors to put him in the field. After impressing on an undercover operation that sends him to monitor a speech by Kwame Ture (Corey Hawkins), he’s promoted to the narcotic division, where he sets his sights on a local KKK chapter.

His success is unwitting and unconventional: what starts as a gag that has him feigning interest in joining the chapter quickly escalates to the men on the other end of the phone quickly buying in. Believing him to be an aggrieved white man, they invite him to a gathering, forcing Ron to quickly hatch an elaborate scheme to infiltrate and monitor the hate group. “With the right white man, we can do anything,” he quips before tapping fellow officer Flip Zimmerman (Adam Driver) to assume his identity for the in-person meetings between “Ron Stallworth” and the Klan. Both officers find themselves essentially working a hire-wire act, one that has them walking a tightrope across a racially-charged minefield that could explode at any moment.

Lee obviously wrings this premise for laughs and suspense, often allowing this wild yarn to unspool with a natural flair of a master storyteller. An opening title insisting this story is “based on some fo’ real fo’ real shit” sets a glib tone that’s downright disarming: we watch as Ron and Flip infiltrate these racist, seemingly incompetent goons (including Grand Wizard David Duke), blissfully unaware of just how dangerous they really are. Both Ron and Flip quickly learn otherwise, prompting both men to reckon with what this operation represents: for the former, it’s a crusade for his people; for the latter, it’s just a job, albeit one that eventually forces him to reconsider his privilege.

BLACKkKLANSMAN features all the requirements of a riveting cop drama: magnetic performances, intriguing plot developments, and genuine tension, all of which coalesce into rollicking, entertaining pulp. Washington brings a subtle swagger to the role of Stallworth, and it’s a tad more restrained compared to the persona his father has cultivated during the past couple of decades. It’s effortlessly cool all the same, though, particularly in the way Washington never dulls Stallworth’s righteous fury beneath the bluster. Much of the film’s comedy hinges on Washington’s cocksure turn, especially when he’s just downright fucking with the Klan, yet he’s careful not to lose grasp of the quiet dignity of a man who often finds himself in undignified situations.

Surrounding him is a top-notch cast of supporting players: Driver is even more reserved, providing a sort of practical counterpoint to Washington’s bluster. Flip and most of Ron’s colleagues — Michael Buscemi, Robert John Burke, Arthur J. Sascarella — depict consummate professionals doing a virtuous job. They’re ideals of cinematic good men, and their steady, upright presences contrast sharply with both the bad elements in their own ranks and the Klansmen, all of whom are (rightly) portrayed as one-note brutes, goons, or fools. Lee obviously isn’t interested in nuance here: these are decidedly not very fine people at all, but rather disgusting, ignorant racists who deserve to have their scheme blow up in their faces.

However, Lee also isn’t content to deliver catharsis through violence, either: at times, BLACKkKLANSMANfeels like a companion piece to Quentin Tarantino’s exercises in historical fiction. While this film is based in truth, it often operates similarly to the likes of DJANGO UNCHAINED, at least on its surface: it’s a rousing, entertaining depiction of justice being served, something we’re sorely lacking in reality at the moment. Some sobering moments are strewn throughout though, as Lee doesn’t want us to lose sight of that cruel reality or what’s truly at stake here. One of film’s most vital scenes, a five minute (or so) dance number at a disco club, isn’t exactly crucial to the plot, but it draws attention to the fact that we can’t take images of black bodies — free to sway carefree, without fear of reprisal — for granted.

Another, even more powerful sequence makes this even more explicit, as Harry Belafonte appears as an elderly activist before a group of college students to tell the tragic story of Jesse Washington, a black teenage farmhand who was lynched in 1916. Lee intersperses the story with actual photographs of the horrific crime, all while cross-cutting between shots of the Klansmen hooting and hollering at a screening of THE BIRTH OF A NATION, creating a staggering contrast between fiction and reality that’s on Lee’s mind throughout BLACKkKLANSMAN. One of the year’s most stunning sequences, it casts the stakes of this film in sharp relief: this is what hangs in the balance, even more so than the retribution Stallworth eventually claims against the Klan.

There’s a conscience to BLACKkKLANSMAN that mostly emerges through Laura Harrier’s Patrice Dumas, the president of the student activist group that Stallworth eventually falls in with. As a romance blossoms between the two, Patrice remains a steadfast, fierce presence that reminds Stallworth that he has a responsibility to his people that he might not be able to uphold as a member of a police force that systematically brutalizes African-Americans. After all, even his own force employs virulent racists who harass her and her fellow students, which forces Stallworth to consider just how effective his work really is. Lee’s eventual answer to that question is certainly complicated, but what’s more important is that it raises that question of responsibility and privilege: Ron remains almost naively ignorant to the plight of his people, as does Flip, a Jewish man who has spent his entire life simply passing as a WASP. On at least one level, BLACKkLANSMAN is about both of these men recognizing that their preconceived notions of justice and responsibility are inadequate in the face of just how abhorrent the Klan is.

Lee directs these questions of responsibility back towards himself, too, as BLACKkKLANSMAN often represents a bit of cinematic self-reflection that finds the director exploring just how complicit this medium has been in shaping American racism. The film opens with the famous scene from GONE WITH THE WIND where Scarlett O’Hara wanders through a train station full of wounded soldiers, and Lee pointedly has the scene play out until the camera pulls out to reveal a tattered Confederate flag.

At first glance, it’s easy to assume this unconventional opening is something like a mission statement about the film’s aim to dismantle and undercut such iconography; however, as BLACKkLANSMAN unfolds, it becomes clear that Lee has fundamental, existential questions about the power of cinema to shape history and reality. Entire generations have wildly misconstrued perceptions of the antebellum south thanks to David O. Selznick’s horribly romanticized monument to a bygone era that nobody would rightfully pine over. Likewise, Belafonte’s activist notes that THE BIRTH OF A NATION — a hideously racist piece of work — was the first American blockbuster that earned praise from Woodrow Wilson and emboldened the KKK’s return after decades of dormancy. The message here seems to be clear enough: if racism is woven into the fabric of America, then cinema did its share in guiding the thread.

Interestingly enough, Lee goes further by not letting himself off the hook: while it features a great shout out to Blaxploitation cinema that seems to be an act of reclamation for the medium, BLACKkLANSMAN continually draws attention to its own artifice. It’s based on history, yet Lee often sketches it in broad, easygoing strokes, almost purposefully dulling the edges: you find yourself almost disarmed by how incompetent and incredibly stupid the Klan is (casting Topher Grace as David Duke is a coup in this respect), to the point where you almost lose sight of just how dangerous they are. Once the film’s climax rolls around, you realize that Lee himself may be engaging with — and drawing attention to — cinema’s power to create illusions. In this case, it’s a feel-good Hollywood fantasy where the Klan blows themselves up, racist cops are outed and arrested, and David Duke is made a complete and utter fool. It’s stirring, funny, and, most of all, just plain nice: it’s what we want to see, and Lee looks to indulge its full potential with an almost surreal image of Washington and Harrier assuming the Blaxploitation mantle by channeling their inner Richard Roundtree and Pam Grier.

But it’s immediately undercut with the sobering image of the Klan off in the distance, bearing torches and burning a cross, suggesting that whatever victory Stallworth can claim is short-lived as those flames blaze on, smoke seguing to an even more sobering epilogue that makes this implication explicit. Footage of last year’s abhorrent white supremacist march on Charlottesville bookends that opening sequence of GONE WITH THE WIND, providing an all too real reminder that the Confederate flag still flies and those Klan torches remain lit, all with the tacit endorsement of a sham president. These are strikingly real images, standing in pronounced contrast to those cinematic images, including those of BLACKkKLANSMANitself, drawing viewers to the conclusion that maybe we don’t need a movie after all but a moment. Artists like Lee can only do so much to tear away at the fabric — it’s on the rest of us to completely unravel the threads to achieve true progress.

Tags: 40 Acres and a Mule Filmworks, : Charlie Wachtel, Adam Driver, Alec Baldwin, America, Arthur J. Nascarella, Ashlie Atkinson, Barry Alexander Brown, Blumhouse Productions, Chayse Irvin, Corey Hawkins, Craig muMs Grant, Damaris Lewis, Danny Hoch, David Rabinowitz, Frederick Weller, Gina Belafonte, Harry Belafonte, Isiah Whitlock Jr., Jason Blum, Jasper Pääkkönen, John David Washington, Jordan Peele, Kevin Willmott, Kwame Ture, Laura Harrier, Michael Buscemi, Monkeypaw Productions, Nicholas Turturro, Paul Walter Hauser, Robert John Burke, Sean McKittrick, spike lee, Stokely Carmichael, Topher Grace

No Comments