Original art by Andy Vanderbilt!

After what what feels like a hundred weeks straight of intense online and in-person debate, after two major-party political conventions, and after at least a dozen times where your not-so-humble Daily Grindhouse editor has been reminded to shut the hell up and talk about movies, there’s only one question our team needed to tackle this week…

What — if any — responsibility do movies have to engage with sociopolitical issues and events? And how about writing about film? Is it possible in a time like we’re living in now to just “shut up and talk about movies?”

PATRICK SMITH: This is an interesting question and I’m honestly having a little trouble figuring where my opinion actually falls. I don’t know if a movie has any obligation to tackle real world issues but I think they should at least have SOMETHING to say about the world at large. Plus, lets be real, importance can be relative and actively pursuing importance feels borderline insincere given the amount hollow would-be award contenders we deal with on any given year. This isn’t always the case: I think SPOTLIGHT and THE BIG SHORT are legitimately important movies in the stories they tell and the facts they lay out and stuff like THE THIN BLUE LINE and MEDIUM COOL capture reality in such a way that they actually change the conversation.

But importance is also relative to person to person and different people bring different angle to different films. Writing about movies, or at least good writing about movies, I think leans into that. I’m way more interested in reading someone having a trans reading of SPEED RACER, or looking at the FRIDAY THE 13th franchise from the perspective of someone with PTSD, or post-war Japanese filmmaking as one long eulogy for the emperor. I’ve read all of these in various outlets over the years and I love them all because its a perspective that I would never have come to myself.

And yeah, sometimes this approach ultimately gets us a lot of think pieces and hot takes that are about as surface level as you can get (albeit well-meaning one) but I’ll take legitimate passion over overtly middling “It’s Good/It’s Bad” approaches to film writing.

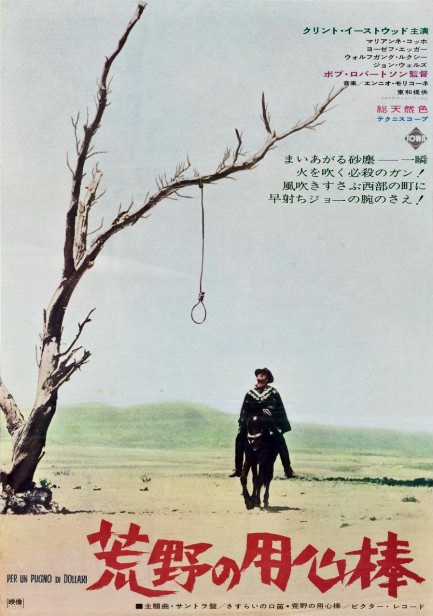

JON ZILLA: I’ve written about it on the site before, but THE GOOD THE BAD & THE UGLY is my favorite movie, which is relatively uncharacteristic for me because it’s one that I’m pretty sure isn’t about anything besides the story it’s telling. That’s not the case with the three movies Sergio Leone made after it, which are consumed with history and myth-making and the discrepancies between the two, but I’ve looked from a bunch of angles now, and it really feels to me like the so-called “Dollars Trilogy” — even the grand finale, the one with the American Civil War as its backdrop — is not really engaging with any profound subject besides filmmaking.

For me that’s an outlier. My love for THE GOOD THE BAD & THE UGLY doesn’t tell you much about me besides the fact that I’m in love with movies. Otherwise, I’m a person who is interested in why people believe what they believe, in what makes people who they’ve become, in why they like the things they like. Those questions can’t get answered without context.

For some people, maybe, movies are solely a means of escapism. Some people love to sit down and turn off their brains, so to speak. I sort of envy that. My brain never really shuts off. I can’t watch a movie without wondering about the time period when it was made, what was happening in the world while it was being made, and what the people who made it may or may not have been thinking. Movies are entertainment and movies are art, but either way they don’t happen without ideas. Granted I’m a movie maniac, and most normal people don’t consume movies like a sixth food group the way I do, but then again, look at the IMDb Top 250, which is the most handy metric indicating which movies are the most popular with “normal” people. The majority of those movies are pretty meaningful, or at least they aspire to meaning. So maybe I’m not as unusual as I think I am.

My favorite overall genre is horror – I would argue (and have argued) that there aren’t a lot of good horror movies that exist in a vacuum. Deep down and sometimes on the surface too, horror movies are about way more than ghosts and monsters. But all genres interact with the real world in one way or another, because all stories are told by people and all people who tell stories have whole lives that are bound to come into play in one way or another when they’re telling their stories.

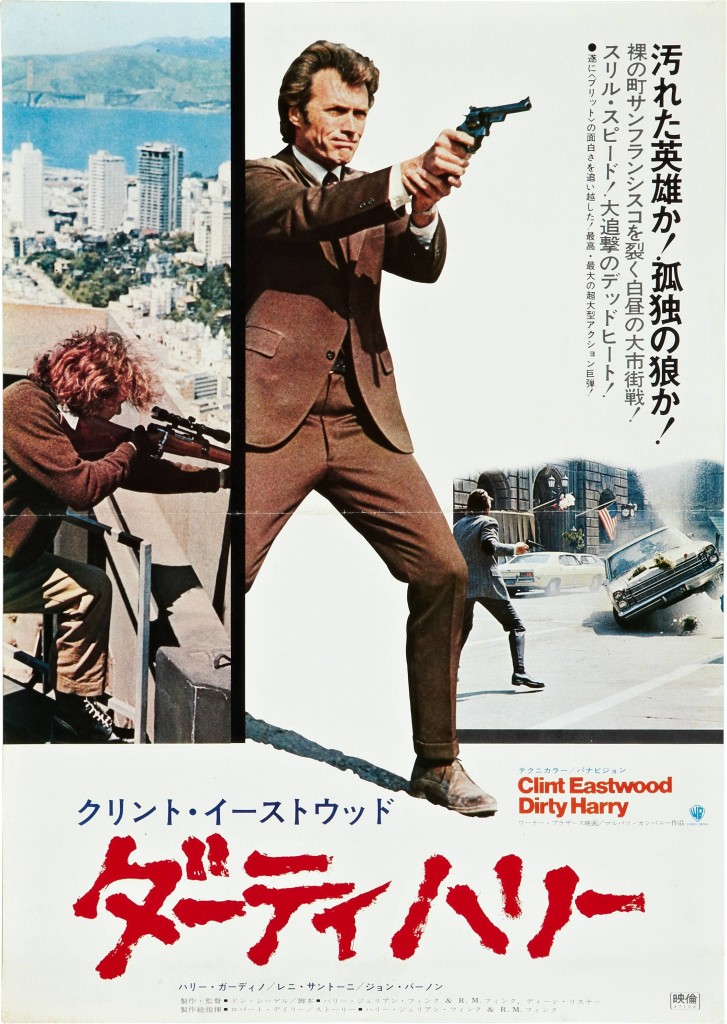

And so it’s the same thing when writing about movies. With no exaggeration, we’re living through an incredibly intense moment in American history, right now. Sometimes I fight the impulse to mention it, but sometimes it bleeds through. It’d be dishonest and immature for me to ignore what’s going on in the world for the benefit of maintaining a superficial conversation about movies. In other words, when people nowadays tell me to stop bringing politics into movie talk, I want to ask – you mean the same way the movies George Romero and John Carpenter and Clint Eastwood and Pam Grier and Charles Bronson made always kept politics out of it? Chances are your favorite artists have strong opinions, whether they’re holding forth or holding back. Chances are that’s why you respond to them in the first place. Not only is it incredibly relevant at this moment in time to consider the reasons, but it can also be lots of fun. Like a crossword puzzle, but with lots more arguing.

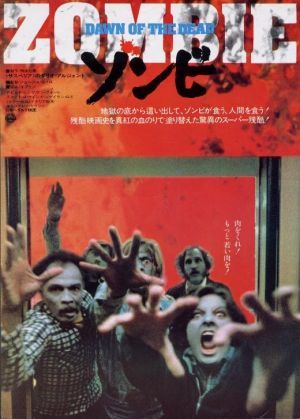

RYAN CAREY: It’s an interesting question, do I think that movies have a “responsibility” to engage with the broader socio-political context that makes their production even possible in the first place? Well, no, they don’t, strictly speaking — but that doesn’t mean that they shouldn’t, or that we’re not better-served as a people when they do.The superiority of the original DAWN OF THE DEAD over its remake, for instance, lies not only in its technical expertise and originality, but in Romero’s willingness to use both zombies and, crucially, human survivors as a metaphor for America’s rapacious consumerism, gluttony, paranoia, and addiction to convenience, while Zack Snyder deliberately chose to strip his version of all those provocative and pointed criticisms and give us a rather bland undead romp. You tell me which one we’re still going to be talking about 50 years from now.

The same is true of us critics — armchair and otherwise. Sure, it’s possible for us to just “shut up and talk about movies” — and the more conflict-allergic of our readers probably appreciates it when we do just that. But for my money I would much rather read — as well as write — reviews that address the various issues and implications that certain films raise than pretend that they exist in some hermetically-sealed “entertainment bubble” that has nothing whatsoever to do with the world around it.

MIA MAYO: I think a movie’s only obligation is to be entertaining. Though if I made A SERBIAN FILM, I totally would have made up something about it being political too just to save face.

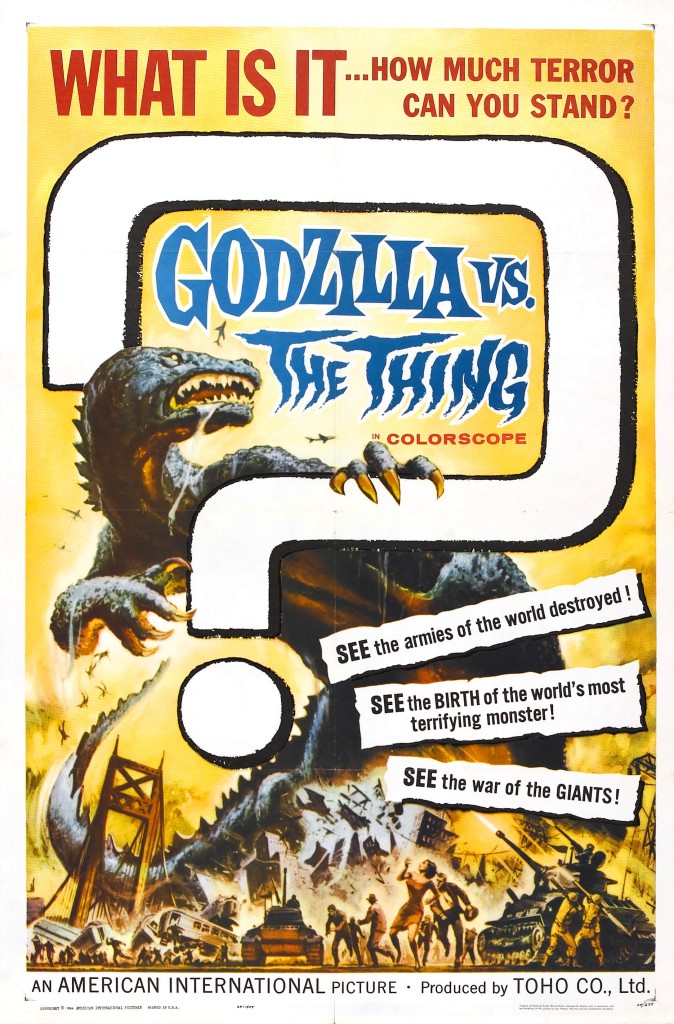

MAC BELL: Film is art. Writing is art. In art, there are no rules. If the artist, whether it is a filmmaker or film journalist, feels the responsibility or passion to tackle sociopolitical issues or events in their art, they should do it. It’s simply up to the individual artist. I personally wouldn’t bring up current political events in a write-up about a Godzilla movie, but there’s probably somebody out there that would. And how fun would that read be?

JON ZILLA: Please don’t get me started on Godzilla…

MAC BELL: Oh the things you could do with a MOTHRA VS GODZILLA piece.

MIKE VANDERBILT: I like politics. I probably started paying attention when I was about 11 years old, thanks to Comedy Central’s Indecision Coverage as well as Bill Maher’s Politically Incorrect. I look forward to Real Time every Friday night after work and listen to plenty of right wing talk radio in my car including Rush Limbaugh, Mark Levin, Michael Savage, and Red Eye Radio with Gary McNamara & Eric Harley (who possibly have the most obnoxious laughs in the world of radio). I like hearing both sides of things, without having to subscribe blindly to one side’s political agenda. I also don’t like to fall down a rabbit hole of frustration and anger when listening and reading to other’s opinions and opt to keep my Facebook feed relatively politic free. Back in my day, politics were personal and private. Why post a bunch of articles that my liberal democratic friends will all like and tell me how correct I am and my conservative Republican friends will incite a fight in the comments section (and vice versa). My closest friends and whoever I make donations to are the only people who need to know my beliefs. Sharing Facebook articles and memes are not going to change things, getting off your ass and demonstrating, hitting the pavement, and donating cold hard cash are the only way to get things done, reposting a biased article from a third-rate news source does not count as political or social activism.. As a half-assed member of the media, I do like to play it closer to the middle and not use Facebook and Twitter as a hologram of myself, but rather as a marketing tool to sell my brand. It feels good to admit that.

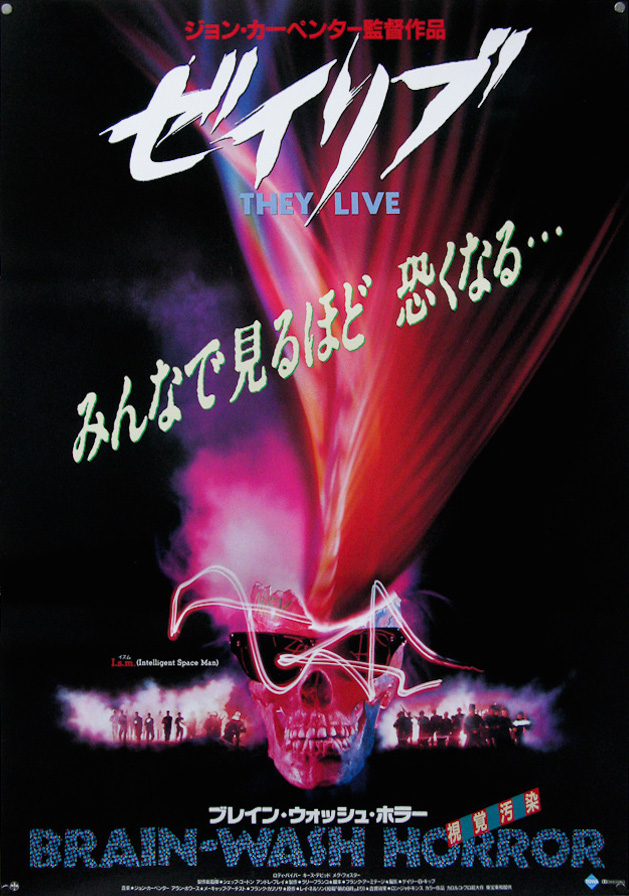

Film has always had a close connection to what is going on the world, be it proactive or reactionary. Film is also a very powerful tool, simply look to the Nazi propaganda movie, TRIUMPH OF THE WILL. Times of great political and social strife change can bring about great films such as EASY RIDER in the ‘60s, ALL THE PRESIDENT’S MEN in the ‘70s, and THEY LIVE in the ‘80s. However, 2016 seems to simply be bringing us more superheroes (some of them are girls now!) and reboots of twenty-year old (and older) properties. Of course, there’s always a need for great escapist entertainment as well.

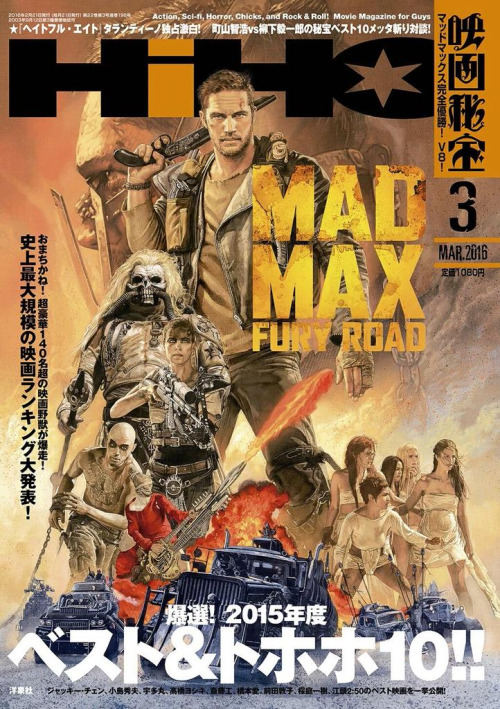

As a film writer, I don’t think it’s necessary to separate film from political and social commentary, as I stated, sometimes it’s quite necessary. I recommend the notion of “picking your battles.” If one devolves into the kind of writer who is constantly whining about social and political problems, you risk becoming a squeaky wheel that everyone ignores. However, I do think critics and audiences need to be aware of the difference between lauding a film for filmmaking and lauding a film for its ideology. Bret Easton Ellis and Quentin Tarantino (two favorites here at Daily Grindhouse) got in trouble two years ago for not being impressed with Ava DuVernay’s SELMA, Tarantino stating that the director “did a really good job on SELMA but SELMA deserved an Emmy.” This writer agreed completely with Tarantino, it felt like a really good made-for-TV movie, but not a great film. However, in certain circles if you approached Selma critically, you were automatically deemed racist. Last year’s best picture winner, SPOTLIGHT I also enjoyed as it simply showed investigative journalists being investigative journalists and taking down the showcasing the hypocrisy of the Catholic Church. However, the movie is not necessarily visually appealing and probably won best picture over the much more cinematic MAD MAX: FURY ROAD because of its ideology, not for the filmmakers skills in movie making. The new GHOSTBUSTERS film was caught in a web of controversy with its all female cast, and some critics didn’t like it including the Chicago Sun-Time’s Richard Roper. While Roper was perhaps a bit harsh in his criticisms, even as someone who gave the film a C+, I couldn’t’ disagree with any of his points. Yet he was attacked on social media for not giving the personal opinion that the public thought he should have. One popular film writer noted that a film such as FURY ROAD could not be reviewed without discussing its social message, I would disagree with that wholeheartedly, a film can and most times should be judged simply as, a movie. Filmmaking and ideology are not mutually exclusive, that’s why film students still study 1915’s THE BIRTH OF A NATION.

BRETT GALLMAN: To an extent, I believe all films are political, since they’re the product of human beings who are presumably trying to communicate something. Whether or not they explicitly engage with specific social and political issues is another thing altogether, but, generally speaking, yes, I do think filmmakers have an obligation to engage with the world around them. Nothing can exist in a vacuum, particularly art, which is always reflective of something. Obviously, artists shouldn’t be forced to consciously, overtly politicize their films against their will, but the best films always have something important to say (or at least provide a rich text for its audience to dig through and interpret). This is especially true when it comes to addressing issues of injustice, particularly since media is a huge factor in socialization and defining “norms” — the longer an unjust situation is allowed to go unremarked upon, the longer we risk having it become codified.

While I can see why some writers would rather avoid its pitfalls (have you seen how awful the internet can be?), I also believe we have a responsibility to use our platform to engage with politics and speak out about those topics that resonate with us. Part of being a good critic is to be informed, and taking an apolitical route is the antithesis of that. We should always be aware of what a film might be communicating and be prepared to criticize* or engage it on those terms. In a perfect world, this type of political writing would always arise naturally from film itself, but if one sees the need to take a stand outside of that, I should hope they would use their platform accordingly. We could always use more people willing to raise hell in the name of justice and equality.

*This is not to say anyone has a license to go back and dismiss decades-old movies as being “problematic,” not that applying blanket statements is much of a criticism anyway.

MATT WEDGE: A film has no responsibility to engage in anything beyond trying to entertain or move an audience. I understand the point of view of people who say, “all art is political.” Some films are overtly political or have an agenda of trying to inspire change (and this does not have to just be liberal change, just look at films like DIRTY HARRY or DEATH WISH to see examples of conservative concerns regarding crime and rapid changes in American society). I think that even the most mainstream, big budget, studio films are political to the extent that they are written, acted, and directed by people who have their own viewpoints on any number of issues, so it is inevitable that their political/philosophical beliefs and concerns would seep into the final edit—no matter how watered-down it might be.

But to say that films—and by extension—writers, directors, actors, crew members, investors, editors, etc. have a responsibility to engage in political or social issues is unfair. It is up to individuals to educate themselves and form their own opinions about what has gone right in this world and what has gone wrong and needs to be changed.

JAMIE RIGHETTI: I think there’s often a misconception that films can ONLY entertain. They certainly serve an important function in that respect but when you dig deeper, even “feel good” movies tend to have a message. One of the most powerful aspects of cinema is to tell stories that might not have made the history books, particularly when it comes to women and people of color. Representation in film is still very much an issue and this is why criticism is important because talking about where film falls short is one way to impact the future of cinema. Holding Hollywood accountable for the lack of inclusion, through feminist critiques and also social media movements like Oscars So White (started by April Reign) is one of the reasons we have seen a significant change to the Academy this year. And that change doesn’t just insure inclusion at the Oscars, it means that diverse viewpoints and stories that represent the beautiful range of humanity have a better chance of making it to the big screen. It means future actors and writers and directors from any background can see themselves as the hero for a change and be inspired to shape the future of film. Digging out these deeper themes enriches cinema and criticism, it doesn’t detract from them. So as critics, we have to hold filmmakers accountable while still remembering why we fell in love with film in the first place. But it’s an easy line to walk if you try.

- [THE BIG QUESTION] WHAT’S YOUR FAVORITE FEMALE ENSEMBLE IN MOVIES? - July 22, 2016

- [IN THEATERS NOW] THE BOY (2016) - January 24, 2016

- Cult Movie Mania Releases Lucio Fulci Limited Edition VHS Sets - January 5, 2016

No Comments