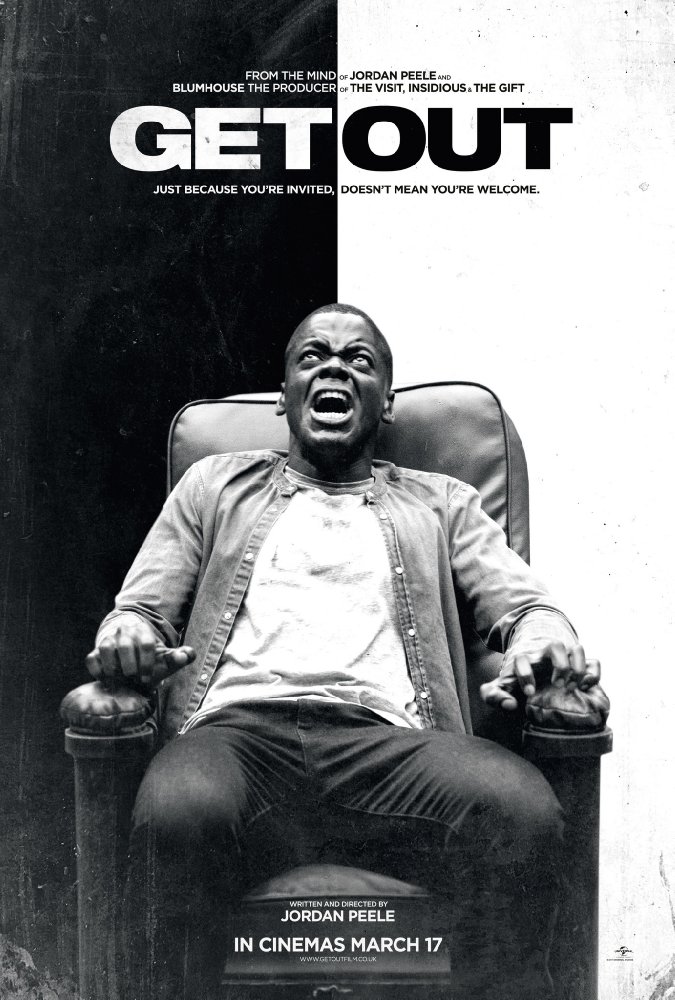

Like so many of you, Anya Novak and Rob Dean both saw and loved Jordan Peele’s GET OUT last week. The use of comedy and building dread, combined with unique social commentary, created a lasting directorial debut in the horror genre that truly stands out amongst many other entries. However, both writers had questions about the ending of the movie, especially considering the long history of horror films critiquing current social problems.

PLEASE NOTE: Obviously this article will delve into the ending of the film, so please beware of SPOILERS and only read it after you’ve seen this excellent movie.

Rob Dean: I wanted to look at how GET OUT ends, in light of the ending of similar films (THE WICKER MAN) and those that Peele cited as influences (THE STEPFORD WIVES, NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD). Which is to say all three movies, and indeed most social commentary horror movies, usually end on a pragmatic downbeat note, with evil winning in some form or another.

While I think the GET OUT ending is satisfactory and works, I wonder why Peele went with a “happy” ending instead of the (more topical) one of having a white cop gun down Chris in the confusion (or something along those lines). The actual/current ending pays off the TSA friend subplot, allows for a sign of hope amidst institutional racism, and suggests that it’s minorities pulling together in the face of adversity that will provide an escape from a heinous cycle. The alternative ending would have been an underlining point to the many instances of racial injustice, and perhaps a bit too heavy handed, but would have also shown that the problems of things like Coagula extend far beyond a small community. In the end, Peele chose an end note of hope over fear, and allows the audience to cheer as they leave behind all of the carnage wrought by the racists.

While we agree it’s a great film, do you think a “downer” ending would’ve worked, or tainted the film?

Anya Novak: I found the ending to be perfect. I saw GET OUT on opening weekend, and when that car pulled up with lights flashing, moans could be heard throughout the audience. We all collectively braced ourselves for what current events have taught us was likely to happen to the black man standing over three dead bodies, one of whom was a white woman reaching for help. Peele knew our expectations, and subverted them. When Rod popped out of the car, the theater erupted in cheers and applause. It was a communal sense of relief, and it allowed the film to end on a sense of hope. Not the “life is unfair” ending that we’ve seen in NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD and THE WICKER MAN, but the “maybe we can get through this” ending of films like JAWS and THE BABADOOK. My interpretation is similar to yours: Peele is emphasizing the power of minority communities when they band together and look out for one another. There was no White Savior here, nor did the TSA agent ever fire a shot.

Personally, I predicted that Chris would get hit by a car (perhaps the cop car from the beginning?), and die on the side of the road, like his mother in the sort of horrific poetic endings that we’ve become used to in the genre. While the film’s social commentary certainly provided for a darker ending, the story allowed for more emotionally satisfying closure. What it comes down to is the writer/director’s intent. While Peele cited Romero and Kubrick as influences, he is making it absolutely clear that he is not Romero or Kubrick. He’s Peele. And though a heavy downbeat ending would have made just as much sense, I’m content with the conclusion we got.

Rob: Excellent point about subversion. I agree that it’s an excellent ending that really brings in the audience for a moment of (much needed) cathartic joy. I do think the film is near flawless, and covers a lot of ground and emotional beats pitch perfectly (even more impressive from a first time director). I just couldn’t help but think about those films that are of the same ilk and why they chose the ending they did.

It’s interesting to point out the historical backgrounds of those influential films: NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD was made in the shadow of the MLK assassination in 1968; THE STEPFORD WIVES was made in 1975, still a nascent time for feminism in pop culture; and THE WICKER MAN in 1973 was just starting to see the fringe conservatives move to power in the U.K. while dealing with the fallout and souring of the Love Generation. Each of those films, couched in genre trappings, were shots across the bow of a burgeoning topic in society and that reflected these inequalities while subversively warning of what’s to come if left unchecked.

While GET OUT was made following the Black Lives Matter movement, it was completed before the current administration took power, with its (at very least tacit) approval and empowerment of the alt-right. Do you think if it were scripted and filmed just a few months later, anything would have changed?

Is the ending a sort of reaction to the times – itself a rallying cry that even something as endemic as the Armitages’ beliefs can be overcome in some way? Contrasted against recent fare like THE GIRL WITH ALL THE GIFTS, is the new socially conscious horror not content with merely reflecting the ills of society but also pushing itself to provide some sort of glimmer of hope or action plan to overcome it?

Anya: I get what you’re saying: perhaps today’s horror is no longer content to cast a mirror upon society, but acts as a more active catalyst for a change of attitude, or catharsis. While I do wonder if a post-election GET OUT would end differently, the film’s main antagonisms (white liberal appropriation and erasure of black bodies) remains unchanged, regardless of which administration is in office. In fact, it’s become even more apparent in light of Trump regime resistance efforts in which white protesters attempt to silence POC by calling their racial concerns “divisive”. It was only with the utter douchebaggery of the All Lives Matter retort that white America began to wake up to the idea that colorblindness can actually be detrimental to those they claim to see equally. Personally, I see fewer people using that phrase since it’s been pointed out as more of an effort to silence than a movement. I like to think that many of the people who used to shout “All Lives Matter!”, or used to wear a ceremonial Native headdress to Coachella for “fun”, or walked up to a black woman and touched her hair without permission… many of these people have been called out by the minorities that they’ve wronged, and have improved their behavior.

It seems to me that Jordan Peele has the same hopes; that these microaggressions and insidious forms of racism can be overcome, and that the power to do so lies in the hands of the marginalized. We’ve seen plenty of “dark endings” in real life, in the countless YouTube videos of police shootings and courtroom acquittals across the nation. I’m not sure that it’s Peele’s entire storytelling style (it’s his directorial debut, after all) but for this particular bit of satirical horror, ending on an uptick works just as well as the more nihilistic ending most of us were expecting. That’s the great thing about the genre: the rules are only there to be broken.

Do you think the current political climate will inspire more concluding messages of hope, or do you think we’ll see more realizations of how bleak things are right now?

Rob: I agree with you, I would like to think that we’re in a period of obstructive erosion where people are becoming more and more aware of their transgressions, entitlement, and privilege. At least, I think that’s happening on a micro level, which is ironic considering the macro levels of discord and division that seem to prevail in this country.

I think that the current political climate is going to lead to much more social commentaries in all forms of art. Part of that is a concentrated effort to raise up marginalized voices by people who have already “broken through,” and by merely telling stories of personal experiences of the outsider becomes a form of critique and commentary on current societal norms. But the other part of that is an artist’s need to process what he or she is experiencing through creating something based on those feelings, which seem to be even more raw and full of activism in the Trump era. So I think we’re going to get a lot more social commentaries coming to us, especially in genre film—which has always thrived when used as a vehicle for deeper thought.

Personally, I would like to see more films follow Peele’s lead and discard the tropes of the past in an attempt to point towards a better resolution. I think a lot of storytellers and filmmakers realize that it’s easy to simply hold up a mirror to society’s ills, but it takes much more courage and talent to suggest a way to break these vicious cycles. While protests against unfair laws and actions by the government are good, turning those protests into action and sustained political change is clearly better. So, too, would films be improved if they were like GET OUT and not only underline systemic issues, but dared to suggest a way out of them. It bodes well that this film exists as it does, with its ending of hope, and suggests that change is coming—if only to a cinema near you.

- [THE BIG QUESTION] WHAT’S YOUR FAVORITE FEMALE ENSEMBLE IN MOVIES? - July 22, 2016

- [IN THEATERS NOW] THE BOY (2016) - January 24, 2016

- Cult Movie Mania Releases Lucio Fulci Limited Edition VHS Sets - January 5, 2016

Tags: Allison Williams, Blumhouse Productions, Bradley Whitford, Caleb Landry Jones, Catherine Keener, Daniel Kaluuya, Erika Alexander, Horror, Jordan Peele, LaKeith Stanfield, Lil Rel Howery, Stephen Root

No Comments