For decades, Cronenberg’s remake was the lonely girl at the dance. Everyone thought someone else asked her out, or wrote a book about her, so she spent a long time alone on the floor — or without a book on the shelf. Emma Westwood was finally the one who took the girl’s hand and a pen, and the two are eternally dancing the jitterbug of film criticism. In Daily Grindhouse’s previous interview with her, she gave us insight on everyone’s favorite genre of violent delights and ends, as well as information on the book she was working on.

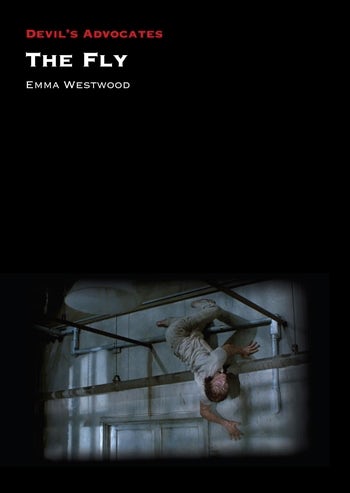

I was going to write a longer review before diving into the reflective interview she’s gifted us but, let’s face it, anyone mildly interested in Cronenberg’s THE FLY is going to buy this book. And if they aren’t they should. Even though the film’s over thirty years old now, there are still new things to learn from it. The DG crowd even has an exclusive look at some fun news that couldn’t fit into her book, which you can read below. Westwood could’ve easily phoned it in and written something that would’ve been a breezy cash-grab, to milk fans the way that many other nostalgia trips have. Instead, she’s written something that’s one-part history lesson and one-part critical essay, something that the hardcore fans can appreciate as well as the people who bumped into it while making their Jeff Goldblum shrine. The facts tucked away range far and deep, from Mel Brooks’ involvement, to the Cronenberg-approved adjective for his work (“Cronenburgundian”). Most importantly, however, everyone is given their due. David Lynch is the first to point out that Mark Frost was an integral part of Twin Peaks, and Westwood’s book points out that Cronenberg wasn’t the only integral part of THE FLY.

Onto the interview proper. It didn’t make much sense to ask her about THE FLY, since she spent almost 200 pages writing about it. Instead, she talks about the technical and creative side of making her book. Well, go on and read it.

How does it feel to be part of the conversation? As long as people are interested in Cronenberg’s film, they’ll eventually come across your book.

I must say, it feels great – just to be part of the dialogue and, hopefully, contributing something fresh to a conversation that’s been going for over thirty years. That’s the thing about great art; there’s always something to say about it. Great art takes on new life with the passing of time, so the way I’ve spoken about THE FLY in 2018 is different to how people were talking about it at the time of its release. One of the main examples of that are the AIDS references in THE FLY – that was a predominant theme in 1986, but now, not so much. The film’s producer, Stuart Cornfeld, confirmed with me that both he and Cronenberg were conscious of the film’s themes relating to the AIDS epidemic at the time of making it, but now Cronenberg has distanced himself from such parallels. Without putting words in Cronenberg’s mouth, I’d say that, in hindsight, he can see that positing the film in terms of AIDS is too reductive – it’s a far broader film thematically with a commentary on mortality, the aging process, and then eventually, death. Cronenberg echoed that in an excellent piece he wrote for The Paris Review where he reflected on THE FLY at the time of his 70th birthday.

How much has your appreciation of the FLY series strengthened since writing your book? Is there one you’d like more people to see?

Everyone should see it. And, yes, my appreciation for the films just keeps on strengthening. THE FLY as a series of films – right from its first incarnation in 1958, through its sequels, to the Cronenberg remake in 1986, then another sequel, and then rumors of unproduced sequels, etc. – is an absolute delight, not to mention an honor, to unpack. The further you dig, the more you discover. And the great thing about it is that you can talk about THE FLY extensively by reaching even further back to Mary Shelley and the writing of Frankenstein, even stories like Beauty and the Beast. I’ve always loved the Frankenstein story, and writing THE FLY has only fueled that love, which is why my next book is going to be about James Whale’s BRIDE OF FRANKENSTEIN from 1935. To talk about THE FLY is to talk about the history of storytelling, really. There are endless things to say. I could have written a book double the size of the one that was published. I even had to shave about 5,000 words off the final manuscript, because it was just getting too big.

There was some excellent information that didn’t make it into the final manuscript due to length reasons, unfortunately. One example was something that came from film commentator Tim Lucas, who was an on-set correspondent on THE FLY for Cinefex and American Cinematographer, and who very generously provided me with his really insightful, unique, and honest point-of-view. In particular, he gave me this – what I feel was a fantastic piece of personal detail that painted a lovely picture about the film’s making:

‘From the first or second day of my visit, I began to hear a highly percussive song playing with obsessive regularity in the crew’s lounge room. It wasn’t long before it got under my skin. It turned out to be “Running Up That Hill” by Kate Bush, who was a new discovery for me at the time. The song became a heartbeat of sorts – a furtive, musky, adventurous, sensuous heartbeat. It gave the place an atmosphere, and I suspect it may have acted as a springboard to some on-set romances.’[i]

‘Being away from home and enjoying the sense of my own individuality for the first time, really, I developed a crush on someone myself, but she and I never spoke until I was literally leaving to go home. It sounds innocent enough – and it was – but it was new and raw and worrisome to me at the time. I started smoking Rothmans and lost more than 20 pounds in those two weeks, just from smoking and circling the soundstage all day and having my little nervous breakdown.’

‘When my second week ended, David tried to get me to extend my stay into a third week, because a lot of the big special effects scenes had been delayed until then. But I wasn’t handling my independence well, and my wife urged me to come home. When I confided the crush to David, he told me that he “really wasn’t surprised” because he had noticed more people hooking up during the course of THE FLY than on any other film set he’d ever been part of. “I don’t know why that should be the case,” he told me, “but it’s true.” I blame Kate Bush.’

Why was your book delayed, and what were your feelings about the wait?

Being patient and waiting for a book to be published kind of goes with the territory of being a writer. It’s the current state of publishing, really – things run on the smell of an oily rag – so little boutique publishing companies like my publisher, Auteur Publishing in the UK, are going to experience delays because they’re running on very limited resources. All of the authors are writing the books without advances or any upfront remuneration, so it means we’re juggling day jobs while getting lost in the gargantuan task that is book writing. I was meant to deliver the manuscript in December 2016. I delivered it in March 2017, and then it took until October 2018 to get it published. It’s like giving birth to a baby – it can be painful at times, and you never really know what’s going to happen, but despite it all, you go back and do it again.

How did you go about turning the mess of notes and interviews into a book, and when did you feel that it was done?

The writing process is an intriguing one – I think everyone, particularly young or upcoming writers, will ask ‘how did you do it or what was your process?’ but it’s more organic than that. I’m sure the writing of my next book will be different to this one, and writing THE FLY was also different to my book before that, Monster Movies. I think, rather than being overwhelmed by it all, I just found a way in – a thread – that I then followed, and let it be woven into something big. I did create a structure beforehand, so I knew what my chapters would be concentrating on, yet that changed a little, because some topics proved to be bigger than others, and I had to split them into other chapters in the final rewrite. For example, for part of the book, I was going to do my scene-by-scene breakdown as just one chapter, but in the end, I broke it into three chapters according to the three-act structure of the film. It’s a very clean, straight-forward, and linear film in its scripting, so breaking it into three acts complemented the structure of the screenplay. I think it worked well.

In shaping your book, how much of it was you and how much of it was your editor? From page layouts to separating chapters to choosing photos.

It pretty much all came down to me. My experience with editors – at least those with non-fiction books – is they defer to the subject matter expert, which is the author. My editor, John Atkinson, would let me know if he felt something was unclear or needed further explanation or didn’t fit into the general editorial template of the Devil’s Advocates series, but otherwise, he let me do what I wanted. That included the choice of imagery, etc – even the front cover image, although I gave John a selection, and then he landed on the image of the ceiling walk, which was my choice anyway. I think, when we first discussed creating this book, his words were, ‘I don’t like to dictate what my authors do.” I’m paraphrasing, but that was the gist. Part of the initial proposal for writing the book required me to pitch the structure of it, so John approved that before I even started writing. That’s not to say he wasn’t open to changes to that structure as the research evolved, and as I’ve already mentioned, I did change the structure.

What about criticism do you love that keeps you from crossing the streams of creating or quitting?

I love the new insights into a film, or any artwork for that matter, that come from criticism. It’s a perfect example of how art is much bigger than its creator, or creators in the case of cinema, because so many people are involved in the creation process. And as criticism becomes more diverse – critics from all different races, creeds, and culture – so do the insights. It’s limitless, and it helps ensure art lives on. There’s a certain insight you get from the filmmakers, but then a different insight comes from critics, and sometimes, the two don’t align. It’s exciting when you hear a filmmaker, in response to a critic, say ‘I didn’t think of it that way.’ I didn’t speak to David Cronenberg when writing THE FLY, which has its pluses and minuses. Of course, I’d love to speak with Cronenberg, but on the other hand, it was great not to have his opinion influence my own. I was lucky to interview at least ten other people who were directly involved in making the film, though, and their enthusiasm for this film, even though thirty years had passed, was really inspiring. It’s a very special film in a number of ways.

In the last interview, you mentioned that you could’ve chosen to write about either THE BROOD or THE FLY. Now that you’ve taken care of Brundlefly, are psychoplasmics still on the agenda? Why or why not?

I’d still love to write a book on THE BROOD but, as it so happens, the publisher I’m working with for my BRIDE OF FRANKENSTEIN – Electric Dreamhouse in the UK – has a book on THE BROOD coming up soon, written by Stephen R. Bissette, who is an American comic book artist and editor [he was an important part of Alan Moore’s legendary Swamp Thing run – RK]. I guess I could still write a book on THE BROOD anyway, but I’m happy to expand beyond Cronenberg’s universe now and try something new. BRIDE OF FRANKENSTEIN might not be in Cronenberg’s universe, but it’s definitely in his solar system. Writing something on BRIDE OF FRANKENSTEIN is going to be interesting because the film is so old, and I won’t have the luxury of conducting my own interviews or getting first-person testimonials.

Which horror movements should people keep an eye on?

That’s a really big question! I think there are some really solid, inventive women horror writer/directors who are doing interesting things in the horror arena, and are worth keeping an eye on. Karyn Kusama, Jennifer Kent, Mattie Do, and Julia Ducournau [Westwood interviewed Ducournau and recorded a commentary with her for the region-free Monster Pictures Blu-Ray for RAW – RK] are all examples of women filmmakers from all over the world who’ve proven they can bring something new and exciting to the horror genre. And I’m not just saying that because I’m a woman. There’s more of a tendency with male horror filmmakers to be derivative of the filmmakers that they’re fans of when growing up – you know, like being the next John Carpenter or something like that – whereas women filmmakers are not shackled with that desire, because they have fewer role models to identify with. Similarly, I think new films that arise from filmmakers who don’t usually work in the horror genre are always exciting – it’s great to see a freshness brought into the genre, because they’re looking at it in a different way. We’ve had some really notable examples of that recently, with David Gordon Green with HALLOWEEN and Luca Guadagnino with SUSPIRIA.

[i] Chris Walas tells us he thought the script superviser, Gillian Richardson, ‘was really cute’; so cute, he ended up marrying her. Walas wasn’t the only one enamoured with Richardson, though – she drew unwanted attention from the film’s resident baboon, Typhoon.

Tags: Books, chris walas, David Cronenberg, Devil's Advocates, Emma Westwood, Filmmaking, Horror, Interviews, John Atkinson, Kate Bush, Mel Brooks, Non-Fiction, Stuart Cornfeld, tim lucas

No Comments