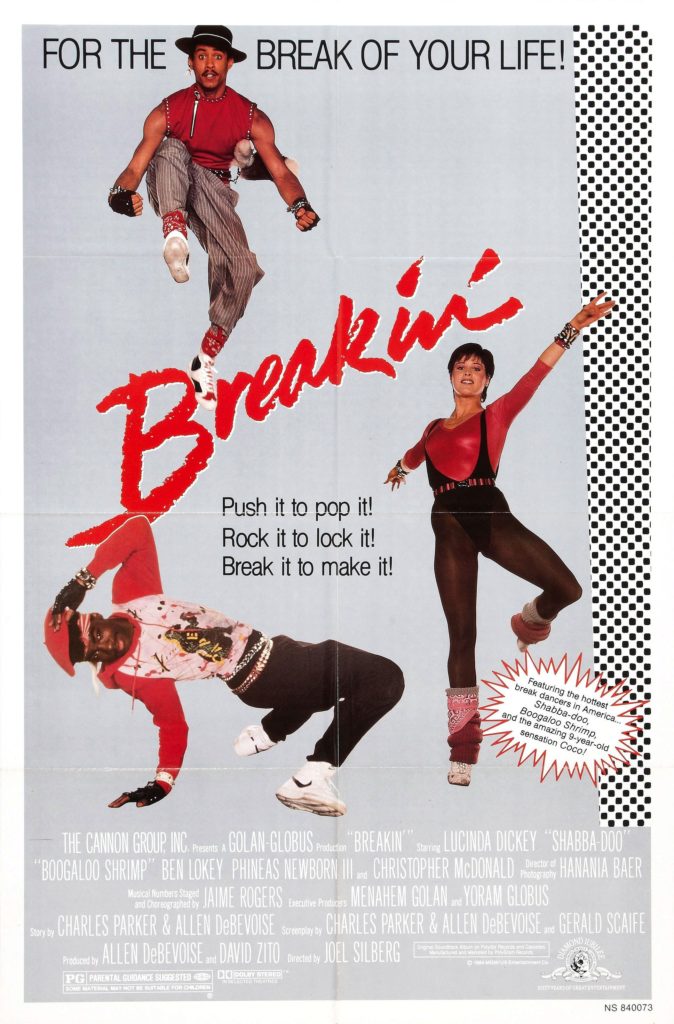

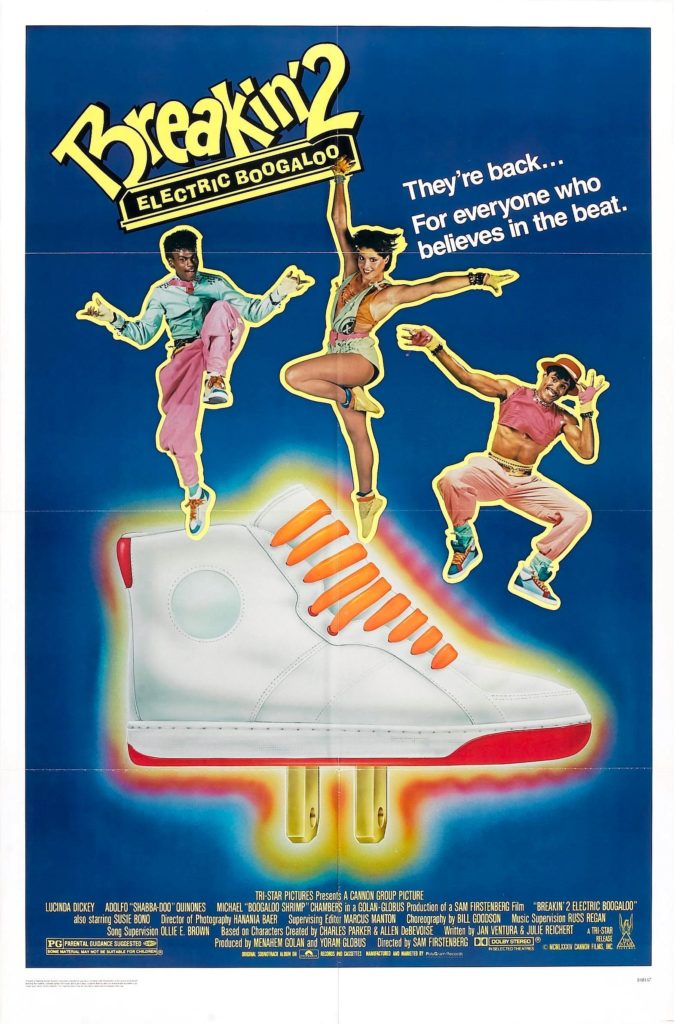

Sometimes the true value of a film doesn’t become clear until years later. Case in point: BREAKIN’ and its sequel, BREAKIN 2: ELECTRIC BOOGALOO. The 1984 original, released by Cannon Films, was designed to capitalize on the popularity of breakdancing. It was a big hit, beating out John Hughes’ SIXTEEN CANDLES in their shared opening weekend and going on to earn an impressive $38.6 million. It was so popular, in fact, that a sequel, BREAKIN’ 2: ELECTRIC BOOGALOO, was rushed into production and released just nine months later. Coming out amid big Christmas movies like BEVERLY HILLS COP hurt its box office take, which stalled at $15 million. Seen today, these pictures – both of which offer substantial entertainment value — are so much more than dance flicks. They have immense cultural value.

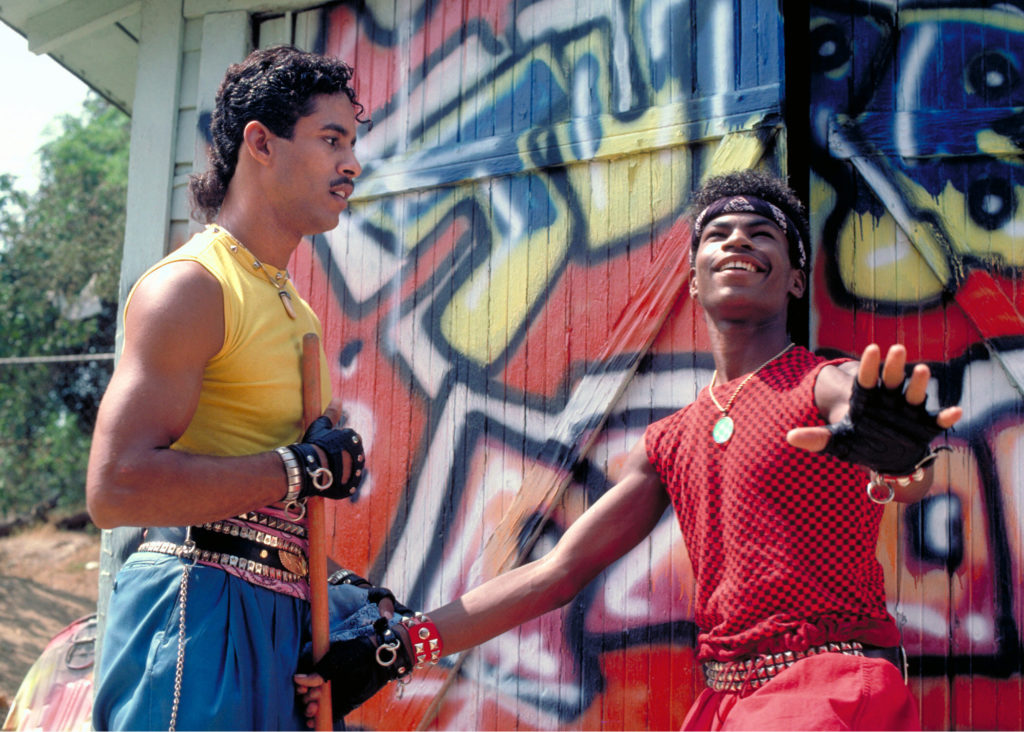

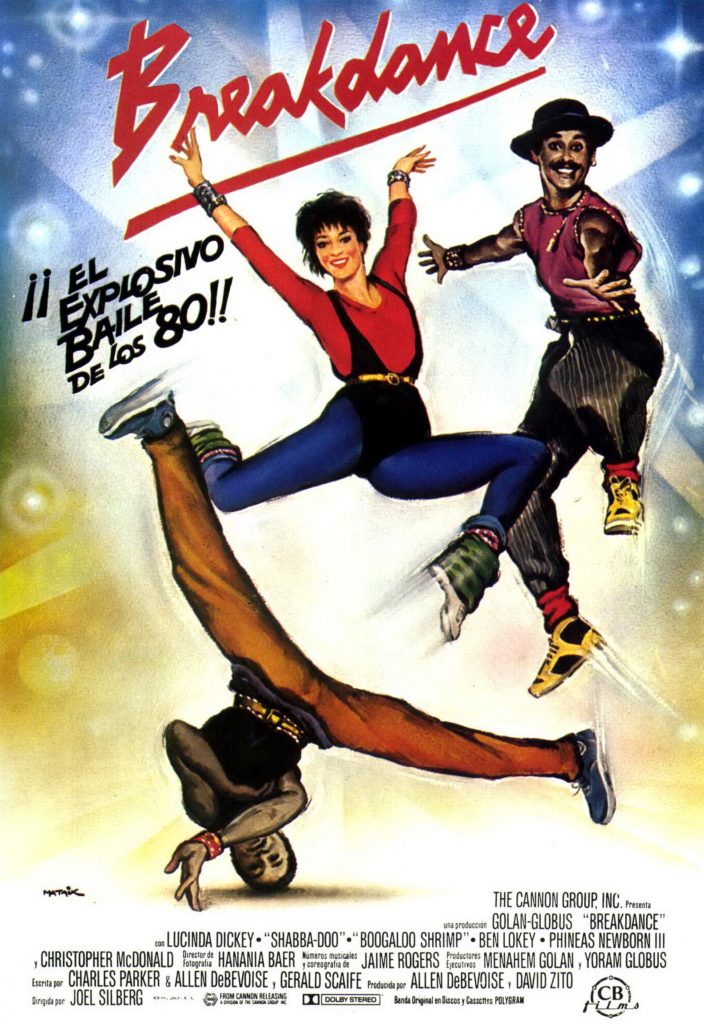

BREAKIN’ is the story of Kelly (Lucinda Dickey), a classically trained jazz dancer. One afternoon, a friend introduces her to two African-American street dancers, Ozone (Adolfo “Shabba Doo” Quinones) and Turbo (Michael “Boogaloo Shrimp” Chambers). They are masters of popping and locking, and Kelly is intrigued by how different their dance style is. Before long, they’re teaching her how to breakdance. This doesn’t sit well with her snooty dance instructor Franco (Ben Lokey), who doesn’t want her making any non-traditional moves. The movie ends with Kelly, Ozone, and Turbo attending an audition, where they win over a panel of skeptical judges with the way they meld her jazz style with their breakdancing. The trio is rewarded with a show designed specifically around them.

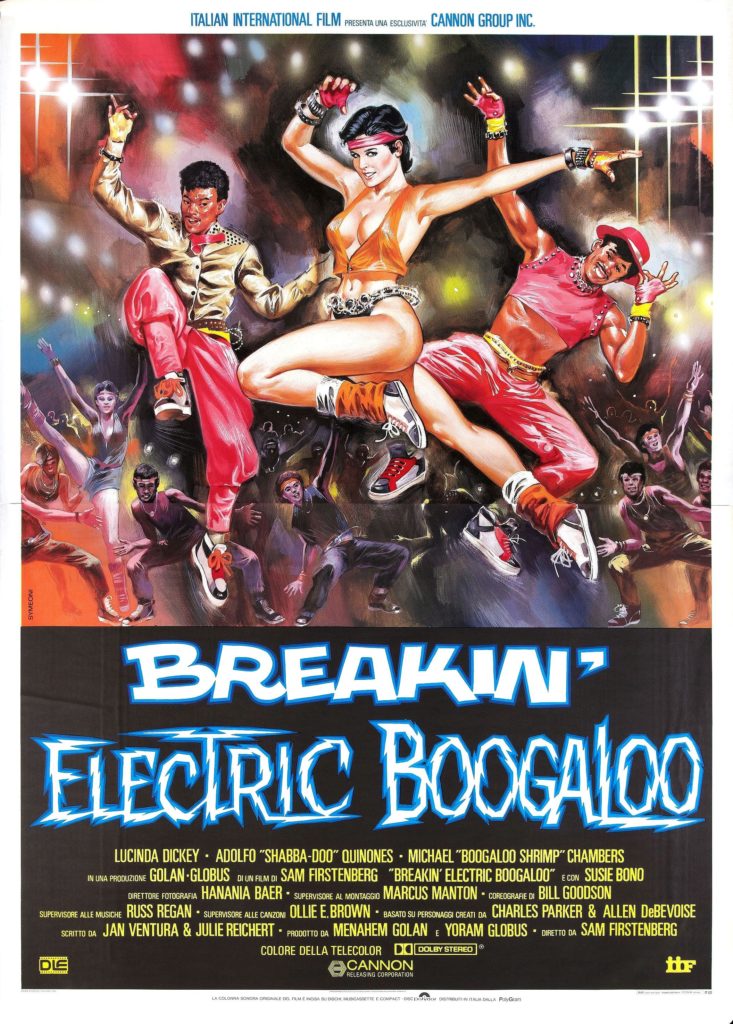

BREAKIN’ 2: ELECTRIC BOOGALOO has become something of a pop culture joke thanks to its subtitle, but it, too, has a lot of energy and joy. The film is set a few months after the original. Ozone and Turbo are now teaching kids to breakdance at an inner city recreation center. A nasty land developer plans to purchase and demolish the facility so that he can build a shopping center in its place. Kelly wants to help protect it, so she approaches her super-rich, ultra-conservative father for a loan. He is appalled that she would show up at his mansion with two street dancers, and refuses. Only one option is left: Ozone, Turbo, and Kelly rally the kids for a great big fundraiser to earn enough money to pay off the center’s debts and keep its doors open.

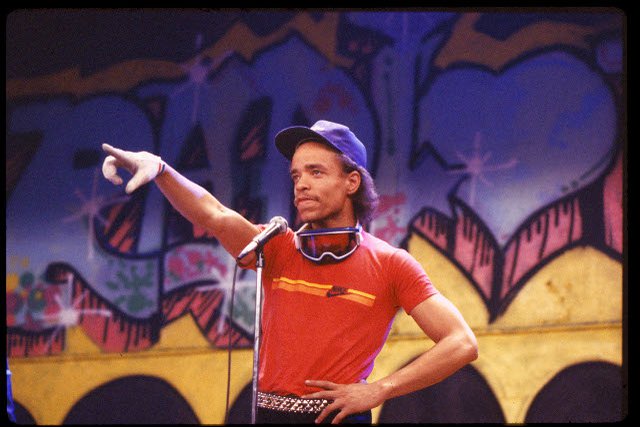

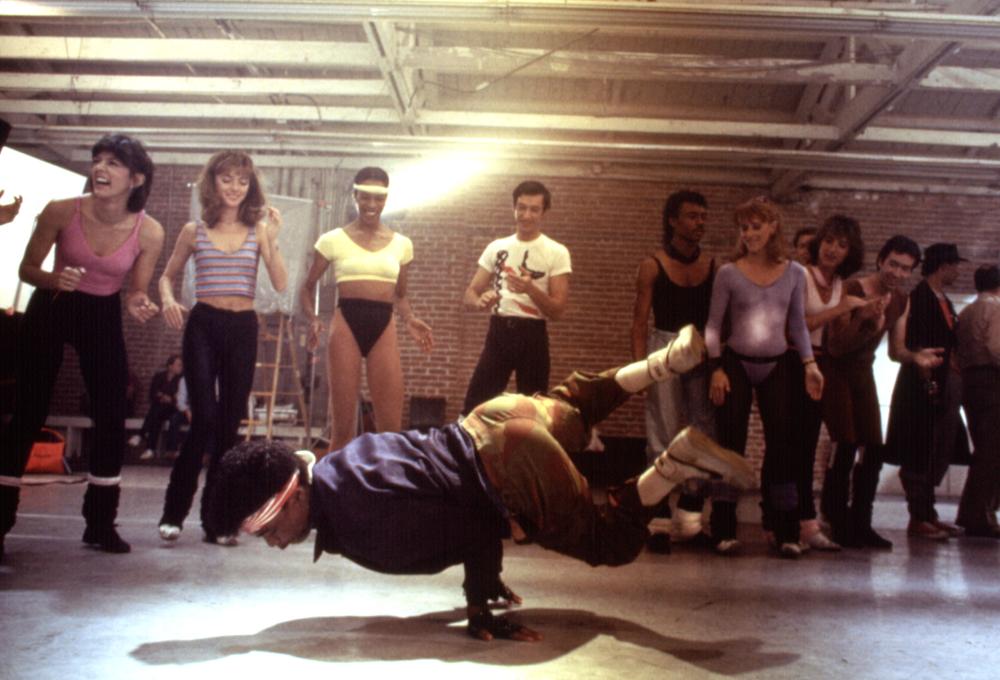

Both BREAKIN’ movies have amazing dance sequences. The original contains one especially memorable moment where Turbo, sweeping a sidewalk, begins dancing with his broom, which eventually takes flight. A dance-off with Ozone, Turbo, and Kelly defeating a rival crew is also packed with impressive moves. In ELECTRIC BOOGALOO, Turbo gets an astonishing 4-minute sequence where he dances on the walls and ceiling of the shack where he and Ozone hang out. These are just a few of the joyous, enthralling production numbers that fill the movies. Quinones and Chambers have a ton of charisma to match their dance talent, making them winning leads. Dickey (a true ’80s dream girl for many male fans of genre cinema) expertly displays talent in a variety of dance styles. Because she can breakdance, too, the stories have a certain authenticity.

That said, there is far more going on here than it may seem from the surface. Yes, both BREAKIN’ and BREAKIN 2: ELECTRIC BOOGALOO are fun in a light entertainment kind of way. You can watch them and simply enjoy the manner in which their plots allow for intricately-choreographed dance scenes. But viewed from a modern perspective, it becomes clear that they also make strong statements about the artistic contributions of the African-American community.

In both pictures, the white establishment characters (Franco, Kelly’s father, the wealthy arts patrons at a fancy soiree) refuse to accept breakdancing as true art because its practitioners are mostly black or Latino, and because it comes from “the streets.” This occurs despite the fact that Ozone and Turbo clearly put as much time and effort into perfecting their craft as Kelly has put into perfecting hers. The commitment to developing their skills is plain as day, yet no one wants to view breakdancing as legitimate. ELECTRIC BOOGALOO‘s community center, meanwhile, is where a racially diverse group of young people hang out. The land developer’s attitude seems to be that a hangout is fine, but only so long as it allows him to take the money of that racially diverse crowd. Art be damned.

Peel another layer off the onion and you can see that it is only through the presence of Kelly – a white girl – that barriers are broken. For example, her father changes his mind after he sees how good she is at the dance style and how committed she is to her friends. And without her presence, Ozone and Turbo would never be able to get in the door for the audition toward the end of the original. Thankfully, the character is portrayed as color-blind and genuine, rather than someone seeking to exploit an art form created by a culture not her own.

Still, there is a long history of African-American cultural contributions being downplayed until a white person comes along and makes them “mainstream.” It’s the precise reason why Eminem, in his song “Without Me,” said, I am the worst thing since Elvis Presley/To do black music so selfishly/And use it to get myself wealthy.

The BREAKIN’ movies are important not just because they recognize this concept; they’re important because they go beyond it. Both films acknowledge the unfortunate truth of African-American art often being under-appreciated until white people appropriate it, then make a concerted effort to put the emphasis where it rightfully belongs. Kelly may give stuffy white folks the feeling that breakdancing is “safe,” but she is still the outsider. Ozone and Turbo are the innovators. They’ve spent countless hours designing, perfecting, and performing groundbreaking moves. They are the heroes. She is merely their eager student. To the movies’ credit, they don’t portray her as the stereotypical cinematic “white savior” who makes things okay for the black characters. Ozone and Turbo are given full respect. What they do is proudly presented as pure, creative, sincere expression, in no need whatsoever of adaptation or modulation.

In each case, the stories are designed to remind audiences that new art forms should be cherished, and their origins and creators should be respected. Where something comes from must never be a barrier. If it’s amazing, embrace it.

BREAKIN’ and BREAKIN’ 2: ELECTRIC BOOGALOO are celebrations of the hip-hop scene in general and breakdancing in particular. They honor the development of fresh ideas that spring from unexpected places and are fueled by passion. Messages like this were hard to come by in ’80s cinema, which is why the BREAKIN’ pictures are far more culturally important than they seem at a casual glance.

If, by chance, you view these movies as cheesy relics of an era gone by, look closer. You’ll be surprised at what you see.

- [DINOSAUR WEEK!] A SOUND OF THUNDER (2005) - June 12, 2015

Tags: Adolfo Quinones, Ben Lokey, Black History Month, Black History Month Week, Breakdancing, Cannon Films, Christopher McDonald, Golan-Globus, Hip-Hop, ice-t, jean claude van damme, Joel Silberg, Lucinda Dickey, Menahem Golan, Michael Chambers, music, Musicals, Sam Firstenberg, The 1980s, Yoram Globus

No Comments